Tilda Swinton's Best Supporting Actress Win For Michael Clayton Remains One Of The Coolest Oscar Wins Of All Time

(Welcome to Did They Get It Right?, a series where we look at an Oscars category from yesteryear and examine whether the Academy's winner stands the test of time.)

You would be hard-pressed to find someone who loves film and doesn't also love Tilda Swinton. With a film career going back to the mid-1980s, she has firmly established herself as one of the most versatile, off-beat, and adventurous actors of her generation, and movie to movie, you never know what she is going to give you. All you know is that it will be magnificent and unlike anything you've ever seen. Swinton has lent her talents to everything from Hollywood studio romantic comedies to period dramas to experimental pictures that put the "art" in "arthouse." She even got roped into the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

What ties her wild, nearly 40-year career together is how very few of her movies have made any sort of a major impact at the Academy Awards. She has only appeared in three Best Picture nominees, and in two of them, they are tiny roles amidst giant productions. That third Best Picture nominee, "Michael Clayton," did feature her in a significant role, and Swinton earned an Oscar nomination for the part of corporate lackey Karen Crowder. Not only was she nominated, but she also took home the award for Best Supporting Actress.

Her performance in "Michael Clayton" remains Swinton's sole Oscar nomination, despite decades of excellent work. With the year in cinema that was 2007, which many of us consider one of the finest for the medium, it's a rather remarkable turn of events that this Oscars newbie could swoop in and take it on her first and only go around, especially when her career has veered so far from what the Academy goes for.

The opposite of populist

There is this notion out there that the Academy does not award movies that people actually see; that they have lost touch with the average moviegoer. Of course, this is a grossly overstated sentiment. Movies that win Academy Awards have to find this balance of reaching some arbitrary standard of artistic achievement and prestige while also finding a way to appeal to a large range of voters that can reach some kind of consensus. The Academy specializes in awarding middlebrow art. I don't mean that derogatorily. I love plenty of middlebrow works. That's just the way it is.

The reason Tilda Swinton has found so little success at the Oscars is precisely because she tends to avoid middlebrow art like the plague. Swinton spent the first decade or so of her film career in the British avant-garde scene with landmark queer experimental filmmaker Derek Jarman being her primary collaborator, appearing in several of his shorts and his last seven feature films. These range from a queer, postmodern adaptation of Christopher Marlowe's "Edward II" to "Blue," which is 79 minutes of a solitary blue screen in which Jarman, Swinton, and others narrate about Jarman's life and his AIDS-related blindness. This is real arthouse stuff.

The closest Swinton gets to the Oscars in this period is with 1992's "Orlando," which was nominated for Best Costume Design and Art Direction. Though it's adapted from a Virginia Woolf novel and features the lush aesthetics of your typical period drama Oscar-hopeful, its examination of gender and sexuality goes so much further than your average Academy member would be comfortable with, especially 30 years ago. Its style may be Oscar-friendly, but its content isn't. If you aren't making middlebrow art, it's hard to break into the Academy Awards.

Entering the mainstream on the margins

Tilda Swinton's first movie, Derek Jarmin's "Caravaggio," was released in 1986. It would take another 14 years for her to appear in a film produced by a major Hollywood studio, and when she did, it was in Danny Boyle's "The Beach." On paper, this seems like a perfect way to get out in front of a mainstream audience for the very first time. Adapted from Alex Garland's celebrated debut novel, this was Leonardo DiCaprio's hotly anticipated star vehicle follow-up to "Titanic" at the height of Leomania, and it was directed by Boyle, who had blown the doors off a few years earlier with his breakthrough film "Trainspotting." "The Beach" could be the way to make a studio movie while simultaneously having a strong artistic voice at its core.

Unfortunately, the results weren't great. Very few liked it, and while it wasn't a financial calamity, it still vastly underperformed expectations, not even matching its $50 million production budget domestically. The movie may not have worked, but Tilda Swinton was at least on Hollywood's radar now. She had reached the status of being able to consistently appear in small supporting parts in mainstream fare like "Vanilla Sky" and "Adaptation.," while also being able to lead indies distributed by specialty labels like "Young Adam."

It really wouldn't be until 2005's "The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe" before the moviegoing world at large would take true notice of Swinton with her striking performance as the White Witch. They could finally start putting a name to a face, coming to realize that she had been doing exceptional work for 20 years, and perhaps now, it was time to recognize her for her work, and she wins for her very next studio film.

The Oscar win

Tilda Swinton winning for "Michael Clayton" was something of a shock. The only major precursor award she won was the BAFTA, and considering she's the only British actor nominated this year, that crossover makes sense. This wasn't even a case of her taking home a bunch of critics' prizes either, just winning a few minor regional awards. Even she was completely bewildered when her name was read.

Making the win even more surprising is the role itself. Best Supporting Actress tends to go to a few different types of performances. You have the firebrands that come in a turn the heat up on the movie, like Arian DeBose in "West Side Story," Allison Janney in "I, Tonya," or Melissa Leo in "The Fighter." You also have the heart-of-the-movie performances, where they act as the emotional center, like Patricia Arquette in "Boyhood" or Youn Yuh-jung in "Minari." And you have the performances that are actually leads that fraudulently get placed in supporting, like Alicia Vikander in "The Danish Girl," Viola Davis in "Fences," and Jennifer Hudson in "Dreamgirls."

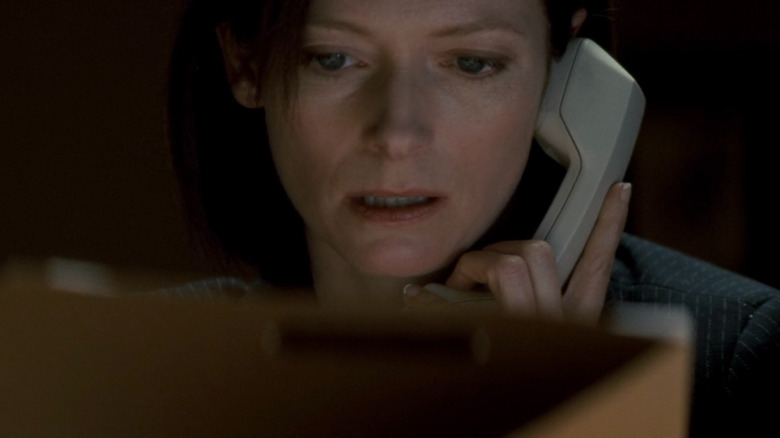

Tilda Swinton in "Michael Clayton" isn't any of those things. She plays a corporate stooge lawyer trying to cover up deaths perpetrated by her company. She's very much a true supporting character, definitely isn't the emotional center of the film, and she doesn't even have the big scene where she tears into some monologue that leaves no piece of scenery unchewed. In fact, her best performance moments are completely silent, like having a silent, sweaty sort of panic attack in a bathroom stall or having George Clooney being the one taking her down to size. It's some of Swinton's best work, but nothing about it screams Oscar. And yet, an anomalous actor wins for an anomalous role.

The competition

Tilda Swinton may have not been the odds-on favorite to win Best Supporting Actress by any means, but that category was always up in the air until Alan Arkin pulled Swinton's name out of the envelope. The BAFTAs, the Golden Globes, the Critics' Choice, and the SAG Awards all selected different winners, with Swinton, Cate Blanchett ("I'm Not There"), Amy Ryan ("Gone Baby Gone"), and Ruby Dee ("American Gangster") winning them respectively. All four of those women, along with newcomer Saoirse Ronan for "Atonement," ended up being nominees, and you wouldn't have been surprised to hear any of their names that night, with the possible exception of Ronan due to the Academy's bias against children.

Amongst the four adult nominees, "Michael Clayton" was the only one of the bunch to be nominated for Best Picture. This Oscars was a battle between "No Country for Old Men" and "There Will Be Blood," and there was not much space in the major categories to award films that weren't those two movies. Had Tilda Swinton not won, the film would have been completely shut out of its seven nominations, making it the only Best Picture nominee that year to not win anything as "Atonement" snagged Best Original Score and "Juno" took home Best Original Screenplay. Every other category "Michael Clayton" was nominated in was a long shot for it to win. George Clooney was never going to beat Daniel Day-Lewis. Same thing with Tom Wilkinson against Javier Bardem. Giving Tilda Swinton this award was not just a recognition of her incredible work but lifted up a movie that time has shown deserved to be in that winners' circle too.

The nomination that wasn't

Immediately after "Michael Clayton," the big filmmakers came calling, and in the next year she was in both Joel and Ethan Coen's Best Picture followup "Burn After Reading" (in which she is absolutely hysterical) and David Fincher's Best Picture nominee "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button." Instead of being this idiosyncratic British character actor who bucks against the Hollywood mainstream at every level, she was now "Academy Award Winner Tilda Swinton," and you can sell that to people in a major way. If she is involved in a project, it immediately goes on people's radar as something that needs to be taken seriously and could perhaps even enter the Oscar conversation. That includes continued collaborations with filmmakers with whom she has worked with prior to the Oscar win like Jim Jarmusch and Luca Guadanigno. However, her tastes are still as odd as ever, and every single time they fall short of Oscar glory. Frankly, they don't even have much of a shot to begin with outside of her reputation being someone major.

The closest Swinton has ever gotten to another nomination came four years after "Michael Clayton" with Lynne Ramsay's drama about the mother of a school shooter "We Need to Talk About Kevin." I briefly touched on this when I covered this race in my very first "Did They Get It Right?" but Swinton not getting nominated this year was rather surprising. She was nominated at the BAFTAs, Golden Globes, Critics' Choice, and SAG Awards and wins the Best Actress prize from the National Board of Review. The hard-edged slot that year instead went to Rooney Mara, who would've been my winner, but Swinton should've bumped any of the other four. In the 12 years since she hasn't even really come close again.

Keep doing what you're doing, Tilda

When a lot of actors win Academy Awards, I think they feel this pressure to remain in that conversation, to be continually validated for their work. They come up in this business dreaming about one day winning an Oscar, and when they do, they just want to feel it again. For the first 20 years of Tilda Swinton's career, awards weren't even a question. The Academy has never and will never recognize the true avant-garde, and that is where Swinton was exercising her artistic muscles. You aren't burdened by expectations or a goal in that space. All that matters is expression.

Her artistic spirit is clearly still driving almost everything she does. She joined the Wes Anderson ensemble, hopped aboard a couple of Bong Joon-ho flicks to play complete wackadoo characters, fell in love with a djinn in George Miller's underrated "Three Thousand Years of Longing," led Apichatpong Weerasethakul's dreamy English-language debut "Memoria," and continues working over and over again with filmmakers she first worked with in the first decade of her career. Coming up, she's going to be in David Fincher's "The Killer" and "The Act of Killing" director Joshua Oppenheimer's fictional feature debut "The End," which is also a musical.

Tilda Swinton has firmly cemented herself as a queen of independent and arthouse cinema, and everyone plugged into those communities will flock to every single project she is in. It doesn't even matter if she ever finds herself in the Oscars conversation ever again. That isn't what her career is about. The fact that the Academy found an avenue to award her is the cherry on top of the sundae. I love that she is "Academy Award Winner Tilda Swinton," but that doesn't define her career. Nor should it.