You Have Chosen Wisely: Why The Last Crusade Is The Greatest Indiana Jones Movie

This post contains spoilers for "Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny."

With the Indiana Jones movies now streaming on Disney+ and "Dial of Destiny" currently in theaters (read our review here), the eternal debate about how the movies should be ranked rages on. On the plus side, no longer is "Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" such an awkward CG orphan, offset from the original 1980s Indiana Jones trilogy by almost 20 years. This is now a proper pentalogy, with the Holy Grail at its center. (No, not "The Da Vinci Code" version, though symbologist Robert Langdon has Indy to thank for his existence.)

After "The Fabelmans," watching "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" is a different experience. Though much of it remains divided along generational lines — raise your hand if you came of moviegoing age in the summer of '89 — assessments of the Indiana Jones franchise have long favored "Raiders of the Lost Ark" as the best film, perhaps rightly so, given its place in film history. If we're being honest, "Raiders" and its unparalleled set pieces (can't outrun that boulder) still offer a tighter all-around piece of filmmaking than "The Last Crusade," which has a few little bloopers, like the case of the disappearing "X" that "never, ever marks the spot" in a Venice library (except when you're looking down on it from above and the floor changes colors).

And yet, while it's not built to withstand the dreaded dings of the CinemaSins counter quite as well, "The Last Crusade" has emerged post-"Fabelmans" as a seminal text in Steven Spielberg's filmography. "Raiders" may be the best overall movie with Indy in it, but from a character perspective, as we head for a deep dive in a runaway tank, "The Last Crusade" truly is the best Indiana Jones movie.

The ultimate MacGuffin: parental approval

"The Last Crusade" is the most nakedly personal film of the Indiana Jones series (in contrast to the "Temple of Doom," where Steven Spielberg is on record saying there's "not an ounce of [his] own personal feeling" in that movie). This three-quel remains light on its feet, but it's an intimate blockbuster that tapped into Spielberg's own unresolved issues with his father at the time. Cross-reference River Phoenix's young Indiana Jones in the opening sequence with "The Fabelmans" and its semi-autobiographical scenes of Boy Scouts in the desert and an aloof, bespectacled father at home.

Not counting the Cross of Coronado, there are actually two main MacGuffins here. Spielberg once called the Grail "a metaphor for a son seeking reconciliation with a father and a father seeking reconciliation with a son." He chased that reconciliation through much of his early filmography, with classics like "Jaws" and "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" showing how a father's relentless pursuit of an idea (be it a shark or aliens) can lead to him endangering or even abandoning his family. Henry Jones Sr. epitomizes that further as the type of movie dad who keeps his nose in a Grail Diary. He would sooner hold up his finger and tell Indy to count to 20 in Greek than turn around from his desk and really see his son.

In "The Last Crusade," Spielberg mined Harrison Ford and Sean Connery's combined star power for buddy comedy, while their characters worked through their father-son baggage everywhere from a burning room to a motorcycle crossing, learning to "let it go" while dangling over a potential abyss at the end. The usual Nazi-punching heroics apply, but by making the relationship between Indy and his father central, Spielberg also gives the movie a heartfelt core that raises its standing.

'The Greatest Show on Earth'

"The Last Crusade" is the best Indiana Jones movie for the same reason "Casino Royale" is the best James Bond movie. Both look beyond the requisite action-adventure stunts and emotionally stunted, chauvinist male bravado. Both strip away their hero's armor, with Indy going soft for a woman and his dad. The fact that "The Last Crusade" brings in Sean Connery, the original Bond, and casts him against type as a clumsy academic (instead of a suave, martini-drinking womanizer) is just icing on the cake.

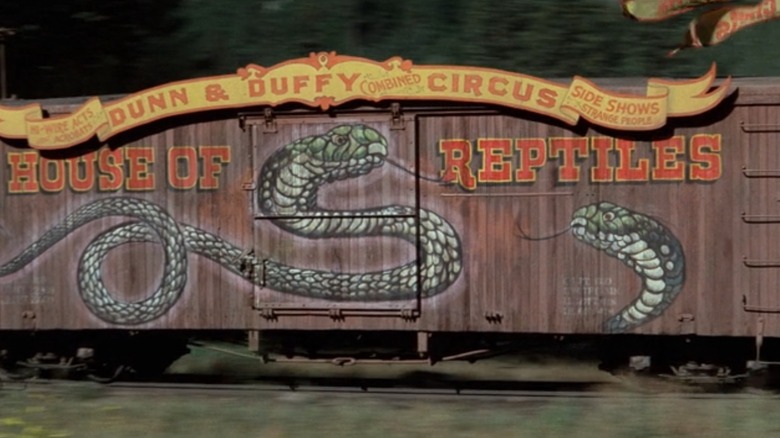

Despite its greatness, "Raiders of the Lost Ark" has some dry patches. There are none of those in "The Last Crusade," which gives viewers the most humor and entertainment value as it gallops along at a circus train pace. Steven Spielberg might as well have emblazoned that train with the words "The Greatest Show on Earth," since that's the name of the movie where one derails and leaves Sammy Fabelman as traumatized as Indiana Jones is by the House of Reptiles.

"The Last Crusade" pulls some moves that would be annoying if not fatal in a modern prequel, showing how young Indy (River Phoenix played Harrison Ford's son three years earlier in "The Mosquito Coast," too) got his signature whip weapon, chin scar, and fedora hat. Yet it makes it work, borne aloft by John Williams' scherzos and whimsical lines like, "He's got our thing!" and "Everybody's lost but me," which boil the MacGuffin idea and our decisive hero down to their purest essence. His motivations for grave-robbing ("This should be in a museum") may be flimsy, but remember, they're just an excuse to reconcile with Dad.

There's another big reason "The Last Crusade" passes the final challenge as the true Holy Grail of Indiana Jones movies. That has everything to do with its protagonist's spirit.

The leap of faith

If a character is defined by their decisions, then "The Last Crusade" contains what is surely a defining character moment for Indiana Jones: when he takes the leap of faith to save his dad at the end. It's a choice that goes against his hard-nosed nature and shows real character growth, which isn't something we always see in the Indiana Jones movies.

"The Last Crusade" is set in 1938, two years after "Raiders of the Lost Ark" and three years after "Temple of Doom." Yet when we catch up with the adult Indy again through a fedora-enabled match cut, he remains largely unchanged after the events of the first two films. This stems partly from the episodic nature of the original 1980s trilogy, which sometimes resists the flow of a logical timeline. Despite being set before "Raiders," for instance, "Temple of Doom" has a callback to Indy shooting a swordsman in that movie.

You could argue that, in "Temple of Doom," Indy outgrows his James Bond-inspired tuxedo and goes from seeking diamonds and "fortune and glory" to liberating enslaved children, white savior style. However, a more consistent character trait for Indiana Jones, across all five movies, is that he's a world-weary rationalist or skeptic who dismisses the mystical powers of artifacts at every turn. He was like this when we first met him in "Raiders" and he told Marcus Brody (Denholm Elliott), "I don't believe in magic, a lot of superstitious hocus-pocus."

For Indy, being a "cautious fellow" means packing a gun in his suitcase, not giving voice to superstition. Here we see how the character overlaps with Harrison Ford's other Lucasfilm icon, Han Solo, who opines in "Star Wars," "Hokey religions and ancient weapons are no match for a good blaster at your side."

Raiders of the lost roots

The final act of "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" takes Indy back to where he started: a cobwebbed temple rigged with booby traps. Again, his footing there is uncertain, so he's got to watch where he steps ... until he makes the leap of faith, without looking down, in a chasm even wider than the one he swung across in "Raiders of the Lost Ark."

In "Raiders," we're told Indy is an occult expert, but he doesn't really believe in the occult any more than a magician believes in stage tricks. You can hear it in the way he talks about the Ten Commandments ("If you believe in that sort of thing"). His self-aware, "shadowy reflection," Dr. René Belloq (Paul Freeman), isn't a believer in any conventional form of prayer, either, since he plans to excavate the Ark of the Covenant as an elaborate "radio for speaking to God."

"Archeology is our religion," Belloq says to Indy. "Yet we have both fallen from the pure faith." You could flip those words, and apply them equally to a movie trilogy where, "Religion is our archeology," and the protagonist is a perennial doubting Thomas.

As a man of the world, Indiana Jones is a pragmatic individual and his globe-trotting adventures usually keep him from putting down roots anywhere or having a stable support group from movie to movie. "The Last Crusade" returns him to his roots, in both a narrative and spiritual sense. We've seen the scene before where Marcus Brody interrupts Indy's class, Indy receives the call to adventure, and they go back to the house and Indy packs. Yet in "The Last Crusade," these otherwise dubious "rhymes," as George Lucas might call them, help put us back on solid ground after the complete unmooring of "Temple of Doom."

Temple of volition

In "Temple of Doom," Indiana Jones is force-fed the blood of Kali instead of the water of Christ. A brownface, red-bearded Thuggee bruiser pries his mouth open, and unlike his leap of faith in "The Last Crusade," none of what happens next occurs of Indy's own volition. He's possessed by the Black Sleep of the Kali Ma, so you can't blame him for getting caught up in the mélange of human sacrifice and off-brand voodoo (in, uh, India?) before his youthful sidekick Short Round (Ke Huy Quan) burns it out of him.

Early in "Temple of Doom," there's an interesting scene where a Shaman (D.R. Nanayakkara) insists that the Hindu god Shiva brought Indy's raft to his village. He believes Indy is fated to retrieve the "sivalinga" (or Shiva linga), a real-life worship object that the movie juices up as one of the imaginary Sankara Stones.

Two characters with opposing viewpoints offer different interpretations of the same event, with Indy assuring himself as much as anyone, "It's just a ghost story." That's easier for him to say before he witnesses the high priest Mola Ram (Amrish Puri) dig bare-handed into a man's chest and pull out his still-beating heart as the man awaits his fiery lava death.

Not content to stop at children in chains, Mola Ram is bent on total religious domination. "We will overrun the Muslims," he says. "Then, the Hebrew God will fall. And then the Christian God will be cast down and forgotten." And, "You don't believe me? You will Dr. Jones. You will become a true believer."

Though he invokes Shiva's name against Mola Ram, and though he confesses the magic rock's power to the Shaman, it's not until "The Last Crusade" that Indy really has the agency to choose belief in something he can't see.

'You must believe, boy'

"The Last Crusade" anchors us back to "Raiders of the Lost Ark" by setting Indiana Jones off in search of another Judeo-Christian artifact with an existing lore that Western audiences know like the back of King Arthur's hand. Still, Indy would rather climb out the window than attend to his duties as a college professor. He has a similar relationship with faith, as does Henry Jones Sr. with his own fatherly duties.

In their conversation aboard a zeppelin, Indy expresses regret that he and Henry were never close, saying, "It was just the two of us, Dad. It was a lonely way to grow up." Henry counters, "I taught you self-reliance," which explains a lot about Indy's character, even as Indy unpacks his father's character and how he's been seeking immortality through academia at the expense of the only family he has left. "What you taught me," Indy snaps back, "was that I was less important to you than people who had been dead for 500 years in another country."

As a recently divorced, first-time father of a three-year-old boy in 1989, Steven Spielberg's range of life experience had broadened, and his real priorities with this movie are laid bare in Indy's dialogue: "I didn't come for the Cup of Christ. I came to find my father." At the same time, Henry reminds us of the Grail crusade's spiritual priorities when he slaps Indy for blasphemy at the crossroads. (Note that a Nazi later slaps Henry three times in return, giving Henry one little arc like the apostle Peter's biblical denials and affirmations of Jesus.)

"At my age," Marcus Brody says, "I'm prepared to take a few things on faith." Indiana Jones has to do that, too, with his father egging him on, saying, "You must believe, boy."

'Why do you choose not to believe?'

Even Han Solo came around to believing in things in the new millennium, as seen in "The Force Awakens," where he again tells two younger characters, Rey and Finn, "It's true. The Force, the Jedi. All of it." The difference with Indiana Jones is that he's much harder to convince.

Putting his father's life in peril in "The Last Crusade" is a sturdy, character-based way to do it. Otherwise, beyond characterization, Indy's stubborn, anti-Fox-Mulder-like refusal to believe verges on becoming a plot hole. Are we really meant to think that, after everything he's seen in his weird and wild escapades, Indy's mind still isn't open to the possibility of luminous things beyond this crude matter?

"Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" unfolds in 1957, which gives it and "The Last Crusade" the same 19-year gap in Indy's fictional chronology as they had in real life. Yet even after adventuring almost two decades, Jones defaults to a skeptical perspective, challenging the power of a new MacGuffin with virtually the same line: "I've heard [this/that] bedtime story before." When he hears Irina Spalko (Cate Blanchett) tout the "paranormal abilities" of "saucer men from Mars," Indy scoffs, "You gotta be kidding me."

"Why do you choose not to believe your own eyes?" she asks pointedly.

Good question. When the Nazis open the Ark of the Covenant, Indy would rather close his eyes altogether than see divine retribution play out. "Don't look, Marion!" he cries. "Keep your eyes shut!"

In "Dial of Destiny," Indy reiterates that he doesn't believe in magic but that, a few times in his life, he's seen things he couldn't explain. That's the understatement of the century, since, among other things, his rich character arc in "The Last Crusade" involves him miraculously faith-healing his gunshot dad with Grail water.

Indy finally hangs on to some friends

"Dial of Destiny" continues the franchise pattern whereby every Indiana Jones movie essentially resets with a new supporting cast. "The Last Crusade" was an early exception to this; it brings back Sallah (John Rhys-Davies) and Marcus Brody and involves them in the plot in a meaningful way, not just as idle cameos for fan service. Fresh off his Oscar win for "The Untouchables," Sean Connery also fits right in and bounces off Harrison Ford perfectly.

Outside his usual academic element, Marcus, like Henry Jones Sr., becomes a source of comic relief. There's no funnier moment than the smash cut from Indy talking up how Marcus "speaks a dozen languages" and "knows every local custom" to the shot of Marcus bumbling his way down a crowded Turkish street, saying, "Does anyone here speak English, or even ancient Greek?"

The only other supporting character who ever returns in the franchise is Indy's first love, Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). "Dial of Destiny" devises a new variation on fridging tropes by having Indy slide a magnet over Marion's face on an actual fridge.

This feeds into Indy's new backstory as a James Mangold cowboy who lost his son and had his "Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" marriage undone between movies. Despite his proven Tarzan skills, Mutt Williams (Shia LaBeouf) apparently died in the jungles of Vietnam. (Meanwhile, Ke Huy Quan is now an Oscar winner, like Connery, but Short Round's whereabouts remain unaccounted for since 1984.)

"The Last Crusade" is a less grief-stricken, more feel-good movie willing to show its humanity through camaraderie with family and friends. "Dial of Destiny" tries to follow suit, only to sideline Marion and Sallah in favor of Indy's new 30-something goddaughter, Helena Shaw (Phoebe Waller-Bridge). The women keep getting younger, while Indiana Jones keeps getting older.

On Elsa and letting it go

Allison Doody was only 21, less than half Harrison Ford's age, when "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" commenced production. Of Indy's three love interests to date, Dr. Elsa Schneider falls squarely in the middle, which seems appropriate given how she plays both sides, the Joneses and the Nazis. She's also in an Oedipal love triangle with the Joneses, which sees her kissing Indy behind his dad's back while the men are tied symbolically.

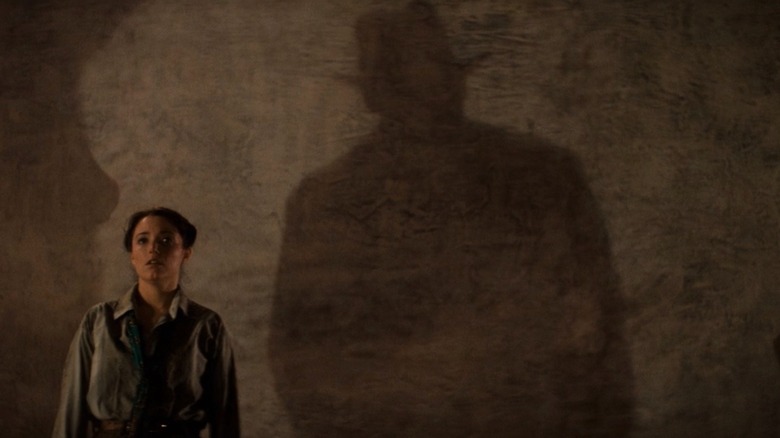

Toward the end, there's a shot where Elsa physically comes between Indy and his dad as she clutches the Grail and jeopardizes all their lives (see above). If, as Marcus Brody says, the Grail quest "is the search for the divine in all of us," then, in light of "The Fabelmans," this shot of Elsa can be read as the metaphorical image of Spielberg's mother chasing the happiness that eluded her in her marriage. Crossing the Great Seal — an imagined boundary that could just as easily mark the line of emotional infidelity in Mitzi Fabelman's relationship with her husband's best friend — rends the temple asunder and causes the earth to open up and swallow Elsa.

Consumed by momentary greed for the Grail, Indy almost falls into the same earthly abyss until he finally gets what he always wanted: his father's attention. At last, Henry sees him and calls him by his preferred name, "Indiana," instead of "Junior" (which lands somewhat like "Mini-Me").

Years before another blonde Elsa, this one animated, sang, "Let It Go," from the snowy mountaintops, Henry uttered those same words to Indy, talking him back from the precipice of spiritual disaster. More than once in "The Last Crusade," we see Henry looking over the edge of a sheer cliff like that, in fear of losing his son.

Plot twist: she's a Nazi

Steven Spielberg uses the visual language of "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" as cinematic therapy for his parents' divorce. After his happy boyhood home fell apart, he lived alone with his dad, as we see Indy and Sammy Fabelman doing at the beginning and end of their respective movies. Yet Spielberg was only half the Indiana Jones brain trust, with George Lucas having created the franchise and helped conceive the story for the first four installments.

Lucas retained sole story credit for "Temple of Doom," and it's there that the franchise began to evolve along more immature, misogynistic lines, in part because George and his wife and editor, Marcia Lucas, had gone through their own bitter divorce three weeks after the theatrical release of "Return of the Jedi." As Marcia and her "Jedi" co-editor Duwayne Dunham later recalled, she was the one who spoke out after viewing an early "Raiders of the Lost Ark" cut, asking, "What happened to Marion?"

Spielberg had left Marion Ravenwood tied to a stake on Nazi Island, but after hearing the reaction of a woman he respected and loved, Lucas went back and shot a new ending as second unit director. This is the ending viewers know, with Indy and Marion together on the steps of the government's "war office," per Lawrence Kasdan's script.

While not a villain, Willie Scott, played by Spielberg's future wife, Kate Capshaw, seems purposely written to grate on the viewer's nerves in "Temple of Doom." Then comes Elsa, the femme fatale who poses as an ally until her true Nazi villainy emerges in a stunning betrayal. By the time we get to "Kingdom of the Crystal Skull," the Indiana Jones series has abandoned all pretense: the woman, Irina Spalko, is now a KGB villain right out the gate.

Guys and dolls

As a gal who can drink men under the table and who, dialogue-wise, gives as good as she gets, Marion Ravenwood has been called a feminist icon, and Karen Allen remains unimpeachable in any and all Indiana Jones franchise criticisms. However, Marion is still a woman written by men, and there are times, even within the same scene, when she reverts, situationally, to being a damsel in distress. In "Kingdom of the Crystal Skull," where screenwriter David Koepp took over for Jeffrey Boam, even Indy seems exasperated by this as he delivers the line, "Oh, Marion. You had to go and get yourself kidnapped. Same old, same old."

Men sling both Marion and Elsa Schneider over their shoulders, but with Elsa, there's that juicy heel turn in the Austrian castle, where she takes charge. It lands like the franchise fielding the prompt: Tell us how you really feel (about women). In this respect, though its gender politics are more regressive, "The Last Crusade" is at least a more truthful representation of where George Lucas and Steven Spielberg were at in their personal development. The movie lets Elsa be what Willie Scott secretly wanted to be: the woman you love to hate, not because she's a shrill gold digger, but because she had the power to hurt Indiana Jones — and used it.

In "The Last Crusade," Indy shows vulnerability. Instead of calling Elsa "doll" (like when he tells Willie he's "allowing" her to tag along and she should give her mouth a rest), he calls her "honey" in a concerned voice. Finally, we're getting somewhere: like good archeologists, digging ever deeper below the façade of boyish wish fulfillment, in which Indiana Jones is the unflappable icon of rugged masculinity and emotional detachment.

An 'aging graverobber' and cradle-robber

"Raiders of the Lost Ark" loses a few points against "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" once you realize that Indy had a relationship with Marion when he was ten years her senior and she was underage (a daisy-fresh girl of 15, going by Lawrence Kasdan's script). As she says to him in her Nepali tavern, where his shadow looms large, "I was a child! I was in love! It was wrong and you knew it!"

"You knew what you were doing," Indy retorts. George Lucas originally wanted to go even younger and make Marion 11 at the time of their forbidden romance, which is not a good look in the year of our Ford 2023, and which would have turned Jones the "aging graverobber" (as Helena Shaw calls him) into more of a cradle-robber with a professorial backstory like something out of "Lolita."

Granted, the Indiana Jones franchise isn't exactly a beacon of progressive values. It traffics in cultural stereotypes from pulp serials of the 1930s, and anyone seeking to impose a modern mindset on movies that old is likely to come up short of agreeable viewing optics. This is a series that knows nothing of walking on eggshells because it's too busy having a Chinese boy (hero of '80s kids everywhere) utter orientalist lines like, "Feel like step on fortune cookies!"

Like Willie Scott sings in her Mandarin musical number: "Anything goes." All the more reason to uplift "The Last Crusade" as a better, more guilt-free Indiana Jones movie, where you never have to think about how awkward it is in "Kingdom of the Crystal Skull," for instance, to see Marion (who once fumed, "Do you know what you did to me, to my life?") beaming up at Indy like the schoolgirl she was when he victimized her.

Losing his religion

"The Last Crusade" gave Indiana Jones the perfect ending, one where he rides off into the sunset and the horizon is at the bottom, just as John Ford recommended to Sammy Fabelman. By the time "Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" arrived in 2008, the world was more cynical, Steven Spielberg's films were more desaturated (cinematographer Janus Kaminski steps in for Douglas Slocombe), and Hollywood had moved past Indy, his boys, and their horses into a new digital frontier. It wasn't at the point yet where actors could cheat death by being digitally de-aged (or resurrected), but here we are.

"Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" opened three years after the cancellation of the cult-favorite HBO series "Carnivale," which also featured a nuclear test — the very first one at the Trinity Site in New Mexico — as a plot point. Seeing Indy roll out of the infamous nuked fridge in the Nevada desert, come face to face with a chittering CG prairie dog, and walk up the hill to survey the mushroom cloud brings to mind the old "Carnivàle" line about how "a false sun exploded over Trinity, and man forever traded away wonder for reason."

Afterward, Indy leans back in his chair and asks his FBI interrogators, "What exactly am I being accused of besides surviving a nuclear blast?" The implied answer is: not keeping the faith.

In "Kingdom of the Crystal Skull," Indiana Jones forever traded away religion for sci-fi, and practical effects for CGI. What's ironic is that the franchise's newfound science fiction aspects — aliens and time travel — coupled with the lost tactility of the original trilogy, actually render it less believable. If the intent was to ground Indy's adventures in a kind of quasi-realism that 21st-century audiences could relate to more than spirituality, it backfired.

Choosing wisely at the end

If there's one constant about Indiana Jones, it's that he keeps collecting women, waifs, and weirdos (like this writer, who put "The Last Crusade" on his list of favorite movies here on /Film in 2021). Some of them even bear nicknames like stray animals, such as Wombat, Mutt, and Ox. "Dial of Destiny" sticks Wombat (a material girl living in an immaterial CG world) with another street-urchin sidekick like Short Round. It's fitting, in the way of "No Time to Die" (which Phoebe Waller-Bridge co-wrote), that hers should be the last face we see before the closing credits roll on the Indiana Jones pentalogy.

After all his time-traveling, there's a certain satisfaction to seeing Indy reunite with his real self-identified partner, Marion Ravenwood. That said, Helena Shaw has to punch Indy out and drag him against his will back to Marion in the present. He's lost the agency he had in "The Last Crusade," where the Grail Knight (Robert Addison) rewards free will with the pronouncements, "He chose poorly," and, "You have chosen wisely."

When he crosses the chasm to meet the Grail Knight, Indy makes a choice to believe at that moment. As much as "Dial of Destiny" might talk about proving things with math and science (insisting that the pseudoscientific Archimedes Dial is not supernatural), that's never what the Indiana Jones franchise was about. It was about the power of God melting Nazi faces.

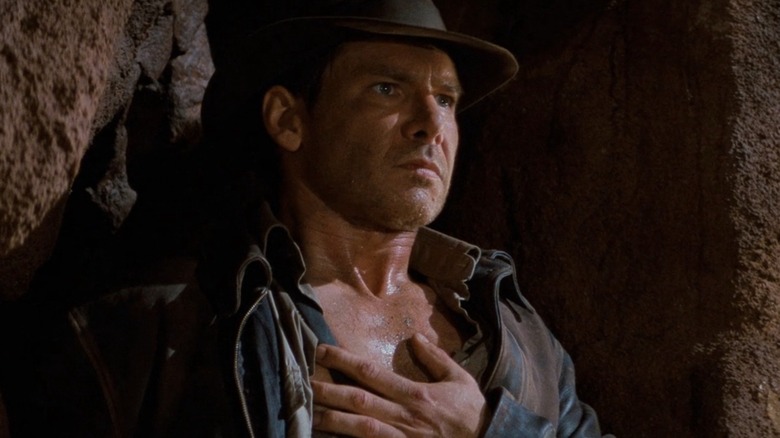

Indy actively flouts the scientific method by ignoring observable phenomena, anyway. The zenith of that comes with his leap of faith in "The Last Crusade." Here, instead of playing the heartbreaker and the bad guy in Marion's story, Indy has his heart exposed: not in a Mola Ram way, but in a quintessentially Steven Spielberg way.

For all these reasons and more, the cup that gives everlasting life is and ever shall be "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade."