Marlon Brando Only Made One Movie With Jack Nicholson, And It Was A Mess

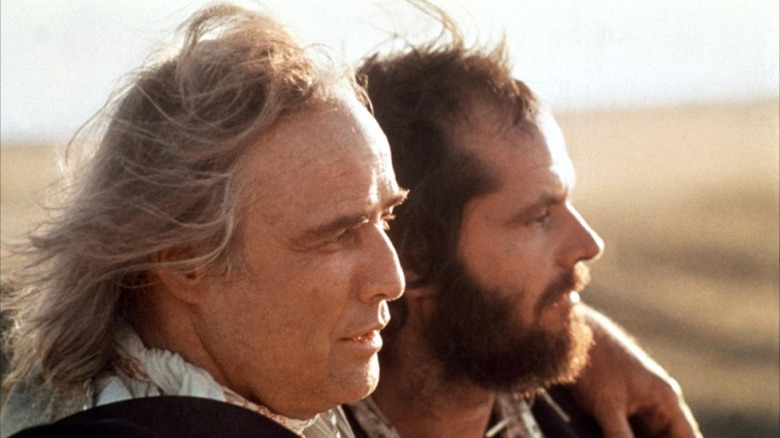

When Marlon Brando signed on to star opposite Jack Nicholson in Arthur Penn's revisionist 1976 Western, "The Missouri Breaks," he'd just reestablished himself as arguably the greatest actor of the 20th century. His Oscar-winning portrayal of Don Vito Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola's "The Godfather" was a transformative coup de cinema, which he followed up with a shockingly primal performance in Bernardo Bertolucci's "Last Tango in Paris." Brando had achieved new, previously inconceivable heights. He had, in the words of The New Yorker's Pauline Kael, "altered the face of an art form."

No one expected an encore. They expected another revelatory turn from this unruly god of method acting. He ramped up expectations by taking a four-year break, upon returning, teaming with Nicholson, who'd just won Best Actor for setting the screen ablaze as Randall McMurphy in Miloš Forman's "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest." Penn had proved with 1970s "Little Big Man" that he knew his way around a revisionist Western, and, perhaps most importantly, that he could manage run-amok movie star egos (like Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman). The conditions seemed perfect for the crafting of something special.

"The Missouri Breaks" is certainly special. Written by Thomas McGuane (and rewritten by Robert Towne), this tale of Montana horse rustlers being hunted by an eccentric regulator is an aimless amble that amuses and confounds in equal measure. It's a classic of the your-mileage-may-vary form, and, unsurprisingly, the most divisive figure in the film is Brando.

A Western epic that rides its own path

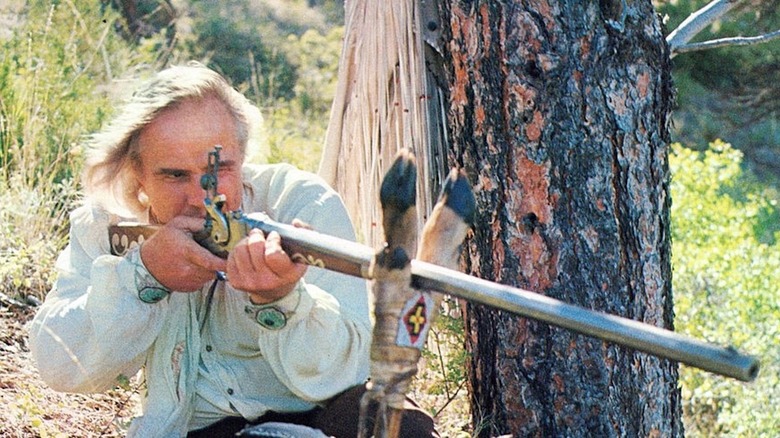

Brando's Robert E. Lee Clayton makes his entrance late in the first act riding off to the side of his horse, all the better to surprise Jane Braxton (Kathleen Lloyd), the progressive daughter of vicious land baron David Braxton (John McLiam). Clayton comes off as a dandyish kook at first, but his reputation as a sharpshooting murderer soon comes into view. This sets him on a path toward a confrontation with Jack Nicholson's Tom Logan, who's nursing a grudge against Braxton for hanging one of his horse-thieving companions, and one of the film's most attractive elements is Penn's eschewal of narrative convention. The story moves at its own pace and presents its violence in a messy fashion, which stood apart from Sam Peckinpah's elegiac, slo-mo gunfights.

"The Missouri Breaks" was also a rough shoot, and not just due to Brando's antics (which Penn humored at every turn). If you've seen the film, the scene where Clayton leaves Little Tod (Randy Quaid) and his horse to drown in a swollen patch of the river is hard to watch because that animal is clearly struggling to keep its head above water as the scene plays out. According to the Billings, Montana humane society, that horse, named Jug, drowned due to negligence on the part of the production. There is also a scene where Brando kills a rabbit with a bladed implement of the actor's own devising. This is obviously unacceptable.

As for the highly touted Brando-Nicholson showdowns, they're strangely inert. Why?

How Brando rattled Nicholson

Would you believe Jack Nicholson was intimidated?

Nicholson, like every actor of his generation, worshiped Brando. He was 13 years younger than Marlon and had been waiting for this moment his entire life. Alas, as he wrote in his 2004 remembrance of the actor for Rolling Stone, Nicholson, after a day's worth of decent work, psyched himself out. Per Jack:

"It started off fine. In our first scene, he's a killer, and I'm hiding out from him. Whatever feelings I had of being intimidated seemed to fit this scene. Then one night after that I made a big mistake: I watched some of Brando's dailies. This was a scene where he's sitting there with John McLiam. I watched nine or 10 takes of this same scene. Each take was an art film in itself. I sat there stunned by the variety, the depth, the amount of silent articulation of what a scene meant. It was all there. It was one of the wildest things I ever put my eyes on."

From that point forward, Nicholson was "annihilated" by Brando, and you can see it. He couldn't hang with him. Nicholson is in the moment, especially during their garden banter where Brando shoots up his crops, but Logan is nowhere near Clayton's equal. Perhaps this is why Penn reduces their final encounter to an extreme close-up that leaves all the acting and (spoiler) dying to Brando.

The film's penultimate scene between Logan and Braxton is far more interesting, but it also drives home how imbalanced the film is dramatically. Brando is in a completely different movie, one that Nicholson, by his own admission, lacked the stones to act in. This was the rest of Brando's career. He sought to dominate and unnerve. Andrew Bergman's screwball lark "The Freshman" is probably the sole exception. It was a good spectacle at times, but it was also a freak show. At least Brando was having a good time.