Asteroid City Ending Explained: I Still Don't Understand The Play

One of the more frustrating frequent critiques I see of Wes Anderson's last few films is their lack of emotional resonance. There's this idea that the further he pushes the artifice in his visual style and amps up his storytelling fragmentation, the more difficult it is to pry into the hearts of the audience members. People look back at "Rushmore," "The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou," and especially "The Royal Tenenbaums" with such a fondness, seeing the way those films are done to be the perfect balancing act. I am not one of these people. In fact, I'm the exact opposite.

My favorite period of Anderson's career has been his 2010s and '20s output, precisely because of the evolution of how he tells his stories, both dramatically and visually. Through all the symmetry, the sets that pull apart, and the narrative framing structures, I find the emotions all the more potent because they are cloaked in so much style, and oftentimes, I am unable to pinpoint exactly why I am so moved by his work. I just am. And I feel Wes Anderson also can't fully articulate the sentiments he tries to get across, or perhaps he just doesn't want to.

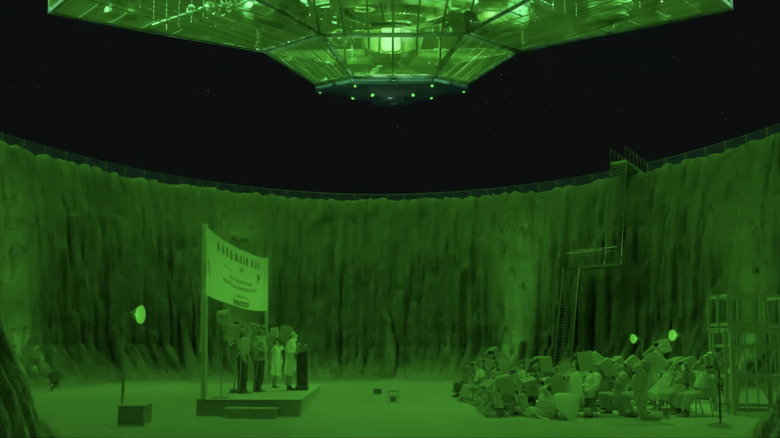

Anderson's latest picture, the magical, sci-fi-edged "Asteroid City," tackles this notion head-on, structuring the film as a play within the movie where members of the cast and crew directly question why the narrative of "Asteroid City" is told the way it is. Most notably is Jason Schwartzman's Jones Hall, the actor portraying the play's lead, Augie Steenbeck, who cannot wrap his head around why his character deliberately burns his own hand in the story's third act. In the arch world of Wes Anderson, the answer to a question like this is rarely straightforward.

Lonely souls forced to connect

"Asteroid City" ostensibly follows a group of people who wind up in the small desert town of the film's title, which boasts a population of under 100 people and features a motel, a gas station, a diner, an unfinished highway ramp, and an observatory along its single street. Amongst the visitors is war photographer and recent widower Augie Steenbeck (Schwartzman) who, along with his three young daughters and "brainiac" teenage son Woodrow (Jake Ryan), has come to Asteroid City for the Junior Stargazers Convention. He connects with career-focused actor Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), who is also there for the convention with her teenage daughter (Grace Edwards). There are several other convention-goers there with their parents, an elementary school class, and a country-western quintet, and all of them become sequestered in this one-horse town after an encounter with an alien.

However, all of this is presented through the prism of a television broadcast, emceed by Bryan Cranston's character, that also chronicles the creation of "Asteroid City" by playwright Conrad Earp (Edward Norton), a Thornton Wilder by way of William Inge figure, and director Schubert Green (Adrien Brody), a Harold Clurman by way of George Abbott type. We see renderings of the casting process, behind-the-scenes drama, and even bits of the story's creation when Earp visits an acting class akin to The Group Theatre, taught by a Lee Strasberg-esque Willem Dafoe. Those resistant to Anderson's storytelling evolutions may regard this simply as a bit of fun nesting doll stuff reminiscent of his other recent work, getting in the way of the "actual" story, but for "Asteroid City" to make an impact, this meta-narrative acts as the connection to the film's true heart.

'Why does Augie burn his hand on the Quickie Griddle?'

When Jason Schwartzman's actor character Jones Hall first meets Conrad Earp about wanting to play Augie, one of the first things he asks the playwright about the script is "Why does Augie burn his hand on the Quickie Griddle?" In the third act while conversing with Midge Campell through the windows of their respective motel cabins, Augie places his hand directly onto the hot grill on which he just made a sandwich. He does not announce he is going to do this, nor does it factor into the plot later, and at a number of points throughout the film, the question about why he does this crops up. During the climax, Jones Hall breaks character and walks off the set to find Schubert Green, his director, to see if he can get some answers. More importantly, he wonders if the performance he is giving is any good if he can't fully understand the motivation of that crucial moment, to which Green assures him that the work is excellent.

Needing a breather, he makes his way out to the balcony of the theatre, and in the adjacent balcony, he runs into the actor who was to have played his dead wife in a dream sequence that was cut, played by Margot Robbie, who recites to him all the dialogue from their emotionally poignant cut scene. The capper to that scene is "All my pictures come out," which is a repeated mantra of sorts the Augie character espouses. For most of the film, this sentence is something of an ego-driven quip, but in this case, it is the sentence that unlocks the actor to perform the remainder of the play.

'All my pictures come out'

Wes Anderson has been lucky to accrue one of the most dedicated and star-studded ensembles of actors in recent film history, who will show up to play in his world time and time again. Unlike most of the filmmakers these actors work with, though, Anderson's style can be exacting. I don't mean this in some dictatorial sense. I mean, the specificity of the composition in every single shot requires a precision rarely matched in other films, and for an actor to be successful within that, they have to give themselves over 100% to Anderson and his material to make the picture sing. Sometimes that amounts to saying a line, performing an action, or gesturing in a way that seems antithetical to one's own instincts and judgments to achieve a desired effect. They are in service to the picture.

When Jones Hall questions Conrad Earp or Schubert Green about why Augie burns his hand, they can't really give him a satisfying motivation, and this feels very true to Anderson's own way of working. Why Augie burns his hand is one of those moments that Anderson puts into his film because in that moment, it's what the story requires of him. The mystery of that spontaneous action is the point, not the logical steps the actor needs to take to have that moment make sense in their own head.

This is why I link this action to the line "All my pictures come out." Augie's pictures, like Anderson's own films, come out the way they are supposed to. It's a similar refrain to "Try to make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose" from "The French Dispatch." The movie is what it is, and Anderson leaves it to us, the audience, to work everything out.

'You can't wake up if you don't fall asleep'

So, if Anderson puts the onus of interpretation on the audience, why do we think Augie burns his hand on the Quickie Griddle? I am drawn to another oft-repeated line from the film's final act, "You can't wake up if you don't fall asleep." Conrad Earp enlists the help of this acting class to find the ending to this story, and one by one, they all directly address the camera with that line, which we have heard in various iterations earlier in the film.

"Asteroid City" examines a group of lonely souls forced to reckon with their situations. Augie, in particular, could not be more withdrawn. His wife died three weeks earlier, and he's been so struck with grief that he hasn't even been able to tell his own kids that their mother is dead. His entire life has been his photography work, and relating to his children without the aid of a partner just isn't in his bag of tricks, causing him to withdraw into himself even more. His only connection is with actor Midge Campell, who is as withdrawn as he is. The alien event and subsequent quarantine throw everything into a tizzy for Augie, and after wondering whether the alien spells doom for mankind, he places his hand on the griddle. That burn is Augie's "wake-up" moment. The griddle wasn't a specific choice. It just happened to be in front of him when he needed a shock to the system.

Whether or not people want to see it, emotion drives everything in a Wes Anderson picture. Those looking for a logic as precise as his framing will leave wanting. If you give yourself over to the picture, though, you'll find everything you need.

"Asteroid City" is currently in theaters.