The Biggest 'Mistake' In Jurassic Park Isn't Actually A Mistake

When I was a young and dumb movie fan, I occasionally frequented one particular website (which will go unnamed but isn't that difficult to figure out) that painstakingly chronicled various movie "mistakes" submitted by readers. Long before the internet bullied HBO into digitally erasing Starbucks cups on the "Game of Thrones" set, this little community kept a running tab on every gaffe ever committed by the industry — continuity errors, factual inaccuracies, visible crew/equipment, and, naturally, the ever-popular "plot holes" concern. Those, dear reader, were dark days.

Many film enthusiasts of a certain age probably went through similar phases of cringe, contributing to a mindset that helped put film discourse in the gutter. I'm not saying this singlehandedly birthed the irritating, gallingly uninformed culture of YouTubers calling for Lucasfilm to fire Kathleen Kennedy and Pablo Hidalgo. It's not like that's how a video channel like CinemaSins could transform from a mildly amusing work of satire to an unstoppable phenomenon that all your former high school classmates on Facebook unironically hold up as legitimate film criticism. And it's certainly not the only reason why movie discussions on social media these days tend to boil down to, "Well, I wouldn't do what that flawed character did, so that's a bad movie." But it doesn't help!

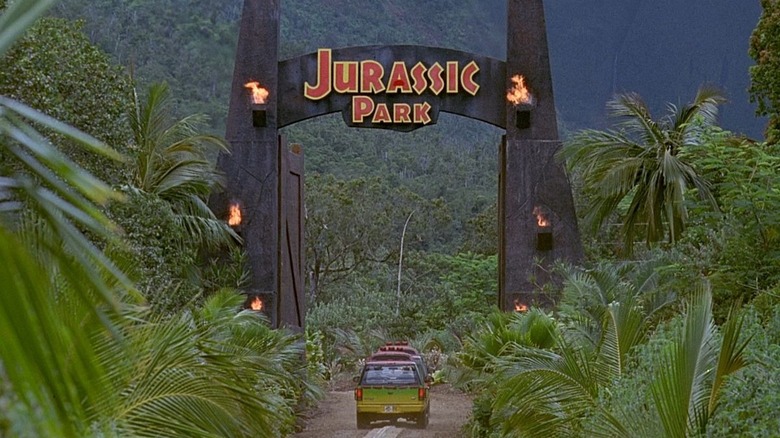

The 30th anniversary of my favorite movie ever, "Jurassic Park," represents the perfect intersection of a universally adored masterpiece that also happens to feature some famous flaws — the magically-appearing cliff in the T-Rex paddock! The T-Rex coming out of nowhere at the end! — that don't actually matter in the long run. But absolutely nothing is worse than the biggest complaint of them all: that the dinosaurs aren't scientifically accurate. Let's set the record straight on why that was never a "mistake" in the first place.

Missing the (dino-infested) forest for the trees

Spoiler alert: As an adventure 65 million years in the making, "Jurassic Park" requires a little suspension of disbelief. Fundamentally premised on the idea that paleontologists could dig up fossilized amber from hundreds of millions of years ago (factually true!), extract perfectly preserved DNA from long-dead mosquitoes (less factually true!), and reverse-engineer living, breathing dinosaurs out of them (absolutely not), the movie is practically begging for experts to call it out as complete and utter fiction. Of course, nobody would ever accuse director Steven Spielberg or the author of the original novel, Michael Crichton, of making a documentary in the first place, but that hasn't stopped countless fans over the years from pointing their finger at the exaggerated depictions of those awe-inspiring creatures and crying foul anyway.

But those who do are also missing a much more important piece of context: Realism was simply never the goal in the first place.

This tends to be a common misconception among certain moviegoing circles, even though such a mindset ignores the fact that storytelling in general (and especially Spielberg's approach to this movie) operates on a different wavelength altogether — one that's completely uninterested in confining itself to rote facts, and rightfully so. Consider the funny anecdote (recounted in this Business Insider interview) where paleontologist and franchise science advisor Jack Horner remembers sitting down with Spielberg during pre-production on "Jurassic Park," explaining how Velociraptors likely featured brightly-colored feathers. As he puts it, "[Spielberg] just started laughing and said technicolor, feathered dinosaurs wouldn't be scary enough."

What Spielberg understood so intuitively is that, if the end result is a better movie, realism should be thrown out the window. Bending scientific fact, fudging geography, and making any other "mistake" is not only fair game. Sometimes, it's necessary.

Baked into its DNA

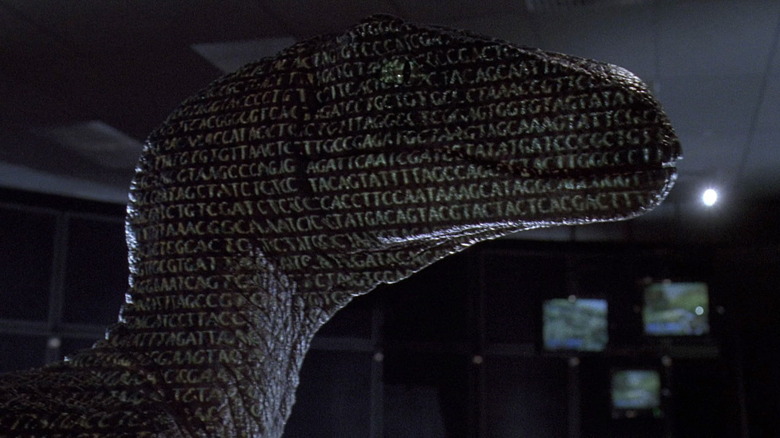

For the moment, let's forget the broader cultural implications of this obsession with holding movies to impossible, mistake-free standards. "Jurassic Park" comes built-in with an even better defense against accusations of its scientific inaccuracy with dinosaur biology. That's because, well, scientific inaccuracy with dinosaur biology was the entire damn point of this story.

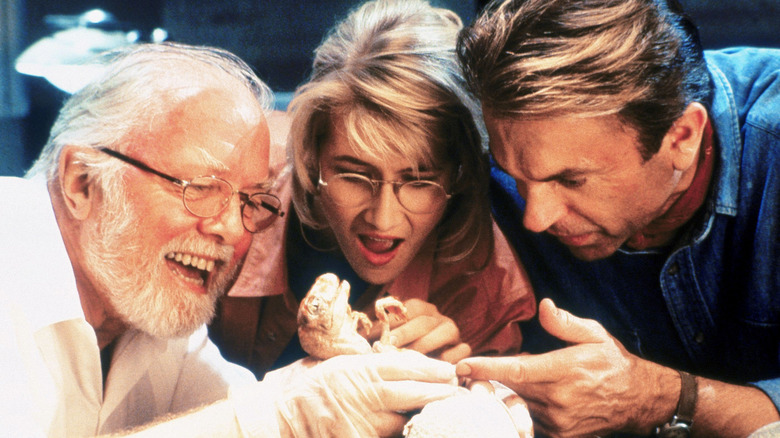

It's all laid out rather succinctly in one of the script's most effective exposition dumps. Scientists "borrowed" DNA from modern animals to plug the gaps in dinosaur gene sequences and, as our characters eventually learn to their peril, those actions have devastating consequences when "life finds a way" — such as when the island's female population of raptors ends up breeding through very un-raptor-like means — to outmaneuver every precaution John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) and everyone else behind Jurassic Park ever took. The inevitable realization is that, strictly speaking, these aren't truly authentic dinosaurs as they once existed in their natural environments in prehistoric times. Rather, these are exactly what Alan Grant would later call them in "Jurassic Park 3" — genetically engineered theme park monsters, created for the express purpose of entertainment.

"Jurassic Park" may not be as overtly (and obnoxiously) self-aware as "Jurassic World" was in 2015, but the original movie neatly addresses all the same concepts that its lesser sequel would attempt to tackle when it introduced the hybrid Indominus Rex. That was meant as a commentary on modern blockbuster audiences needing a bigger and better spectacle to stay engaged (as explained in further detail here). Yet even so, the 1993 classic was ahead of its time, showing how the motivation behind the first dinosaur theme park came from the exact same place of needing to impress visitors by any means necessary — even if that meant turning fact into fiction.

Leaving a mark

Given how much the "Jurassic" franchise has monopolized practically all depictions of dinosaurs in film lately (thank goodness for Apple's "Prehistoric Planet" and the recent Adam Driver-starring "65"), it's worth discussing how the original film set the template for these iconic creatures — not just for the subsequent sequels, but the general public's perception of dinosaurs in general.

How's this for the power of cinema? Those who watched "Jurassic Park" back in 1993 (and multiple generations thereafter) came away convinced that the T-Rex actually did hunt its prey with vision based on movement, that the human-sized Dilophosaurus must've had neck frills and spit venom, and that Velociraptors were genuinely six-foot-tall killing machines smart enough to open doors. In reality, the T-Rex was likely a scavenger with great vision, the Dilophosaurus was 20 feet long without any evidence of flashy ornamentation, and Velociraptors were more reminiscent of feathery chickens. Unlike any other movie, "Jurassic Park" did more to affect public perception of an entire group of extinct animals than any school textbook could hope to compete with. As much as paleontologists and teachers might (justifiably!) groan about having to undo such a lasting impression on our collective psyche, it also speaks to the inescapable truth of how the best movies and greatest feats of storytelling can influence our imaginations.

At its heart, "Jurassic Park" is a throwback to when summer blockbusters could multitask effectiveness, heart, and ambition without compromising one in favor of the others. Maybe audiences were a little less cynical back then, more willing to forgive perceived flaws in favor of an unforgettable experience. Most likely, we just need a reminder that the age of big-budget thrill rides — ones that know how and when to break rules — doesn't have to be extinct just yet.