Jurassic Park's Paleontologist Adviser May Have Inspired Its Main Character

When Michael Crichton was cooking (which was a lot less frequently than his bestselling output suggests), he used real-world scientific fears and advancements to craft bestselling corkers that could zap the boredom from a cross-country flight. Books like "The Andromeda Strain," "The Terminal Man," "Congo" and "Sphere" hooked us because Crichton either had the expertise (he received a BS in biological anthropology from Harvard and briefly attended the institution's prestigious medical school) or did the research to write conversantly about highly specialized topics like psychosurgery and semiconducting diamonds.

Crichton perfected this formula, at least in terms of book sales, when he knocked out "Jurassic Park" in 1990. His melding of genetic engineering and humanity's fascination with the giant creatures that ruled the earth long before our evolution into sentient beings capable of ending our own existence sans astronomical assistance was a blockbuster before a single copy was sold. When word got out that he'd written a techno-thriller that plausibly posited the return of dinosaurs to the planet, a bidding war broke out. Steven Spielberg, who'd been developing a hospital project with Crichton that would eventually become "ER," had the inside track and implored Universal Pictures to spare no expense in acquiring the rights.

Commercially, this was a perfect marriage. Spielberg wound up needing a bonafide smash after "Always" and "Hook," and the narrative elements played to his strengths — particularly the kid-hating protagonist, Dr. Alan Grant (Sam Neill). A rugged paleontologist who values digging above all else, Grant gave Spielberg an engaging character through which to explain dino behavioral theories that reached beyond the monster-movie silliness of "One Million Years B.C." We like Grant. We trust Grant. And this is because Grant kinda-sorta exists.

Jack Horner loves dinosaurs, but how does he feel about kids?

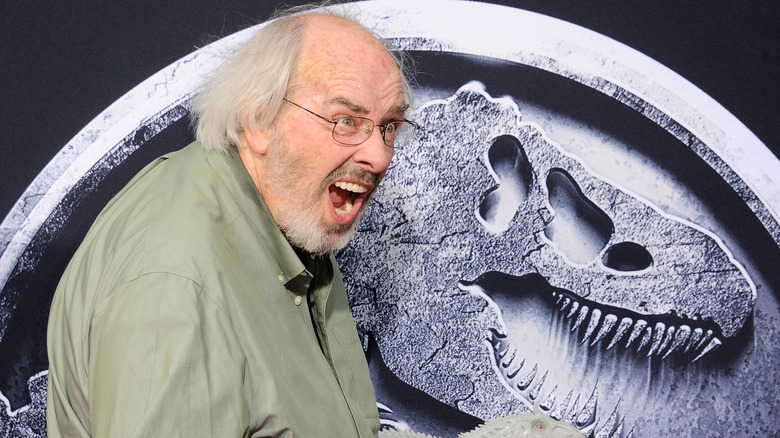

Michael Crichton's "Jurassic Park" might not exist without paleontologist Jack Horner. He advanced the theory that some dinosaurs were social creatures, meaning that they nested and traveled in flocks like birds. Like Grant, Horner is from Montana and has made his name as a digger. Though Horner did not read the novel upon its release, a friend checked it out and informed the dino expert that the character of Grant seemed to be inspired by him.

According to a December 2014 interview with Smithsonian Magazine, all Horner wanted to know at the time was whether he got eaten by a dinosaur. He was pleased to learn that the answer was no. Horner had the same question for Steven Spielberg when the director asked him if he would serve as a technical advisor on his movie. Upon learning that Grant would not serve as dinner for a carnivore, he signed on.

One of Horner's roles on the production was to help Sam Neill with his portrayal of Grant. But his most important function was to be an expert sounding board for Spielberg. As he told Smithsonian:

"My job really was to work alongside Steven and answer his questions for him [and] to confirm with the computer graphics people ... My job was to make sure that [the dinosaurs] looked accurate and that the movements that we're sure of, that they would be accurate. Basically I was there to make sure that sixth graders didn't send him nasty letters about something being wrong."

Alan Grant might exist, but dino DNA does not ... yet

If Steven Spielberg received any nasty letters from sixth graders, it was likely because their favorite dinosaur didn't make the final cut. Fortunately, Jack Horner hung around for the next two "Jurassic Park" movies (and returned for the second trilogy) to ensure that other genera would be portrayed with some degree of accuracy.

As for the potential of a real Jurassic Park in the near future, Horner was down on the extraction of DNA from mosquitos in 2014, telling Smithsonian:

"We have tried for years to get DNA out of a dinosaur and out of a mosquito and out of amber, and tried to get the DNA out of the amber itself, and haven't had any luck yet. DNA is a huge molecule and it doesn't hang together very well, so it comes apart. And as far as we know, to date we certainly have no DNA from a million years ago."

But there have been two significant discoveries of late. In 2020, paleontologists probing the 75-million-year-old fossilized remains of Hypacrosaurus nestlings uncovered evidence of proteins, chromosomes and, yes, DNA. As for our fragile genetic building blocks surviving in amber, researchers recently found DNA preserved in the two-to-six-year-old remains of ambrosia beetles encased in the resin of amber in Madagascar.

So if you're rooting for science to keep pioneering new ways to jeopardize the future of humanity, take heart! We'll never live to see it, but one day our successors could very well get to live in fear of being a Tyrannosaurus Rex's midday snack, at which point the revolutionary visual effects of "Jurassic Park" might at long last look antiquated.