How Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut Changes The Movie (For Better Or Worse)

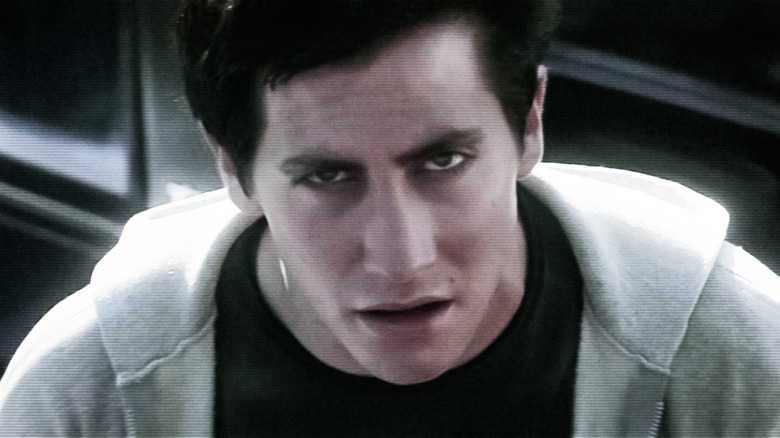

"Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut" immediately establishes itself as a different viewing experience from the original 2001 film, as Jake Gyllenhaal's teen protagonist rides his bike home in his pajamas to a new soundtrack song. Echo & The Bunnymen's "The Killing Moon" is such a signature needle drop that it feels a little off to hear it replaced by INXS's "Never Tear Us Apart."

It's as if writer-director Richard Kelly is now cueing the audience through music that it's about to enter a new "Tangent Universe," apart from the Primary Universe, just as Donnie himself does in one interpretation of the film. That interpretation gets a stronger push in "Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut," which introduces those capitalized terms onscreen and pulls another soundtrack switcheroo later when it replaces composer Michael Andrews' recognizable "Liquid Spear Waltz" with a piece of opera music.

George Lucas famously changed a song at the end of "Return of the Jedi" when he did the Special Edition re-release of the original "Star Wars" trilogy, but by then, almost 15 years had elapsed since the first version of the movie hit theaters. "Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut," by contrast, did its liquid spear waltz into theaters in 2004, just three years after Kelly's original film — which had bombed at the box office, only to find renewed life as a cult classic on home media. (Hence, the theatrical re-release.)

"The Director's Cut" contains almost 20 minutes of additional footage not found in the first theatrical cut of "Donnie Darko," including new and extended character interactions. We're not going to laundry-list every single change here, but what we will do is talk about how those changes alter the film's overall narrative thrust — for better or worse.

The Tangent Universe and ending explained

As Radio Times notes, the most significant alteration in "Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut" is the appearance of pages from Roberta Sparrow's book, "The Philosophy of Time Travel," onscreen. These pages give the film appropriately non-linear chapter headings, and if you can get over the esoteric wording, they explain in no uncertain terms what's happening throughout the movie.

Rather than use common phrases like "parallel universe" or "alternate reality," Sparrow, a.k.a. Grandma Death (Patience Cleveland), writes of an unstable Tangent Universe that will last "for no longer than several weeks." This goes along with what Donnie's seemingly imaginary friend — the six-foot-tall rabbit, Frank — says at the beginning of the movie when he warns him about the world ending in 28 days. That warning comes after Frank has lured Donnie out of his house, just before a jet engine falls out of the sky and crashes through his bedroom ceiling.

Donnie was supposed to die, but as one of his friends says, he "cheats death," and everything from that point forward (until the end of the movie, when it returns to Donnie laughing in his bed on October 2, 1988) is a Tangent Universe. Viewers of the original "Donnie Darko" could certainly arrive at this interpretation on their own, but "The Director's Cut" puts the text up onscreen confirming it and explaining how the Tangent Universe will eventually "collapse upon itself, forming a black hole within the Primary Universe capable of destroying all existence."

This reduces the ambiguity of "Donnie Darko," which originally gave the audience more leeway to develop other possible theories. In order to save his girlfriend and the universe, Donnie has to go back in time, accept his fate, and allow himself to die at the end.

Show-and-tell with The Philosophy of Time Travel

Perhaps the most blatant example of "Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut" overexplaining things comes when a page from "The Philosophy of Time Travel" introduces the idea of a metal "Artifact" that provides "the first sign that a Tangent Universe has occurred." The movie superimposes this explanatory text over imagery of the jet engine being removed from Donnie's house, leaving very little room for imagination as to what the Artifact here is.

At the end, "Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut" also juxtaposes images of the people Donnie saved, waking up, with text about the Manipulated Living and Dead and how, when "they awaken from their Journey into the Tangent Universe, they are often haunted by the experience in their dreams." The unmasked Frank (James Duval) — whom Donnie shot in the eye after Frank accidentally drove over his girlfriend, Gretchen (Jena Malone) — touches his eye as if he remembers, and is indeed haunted, by what happened to him in the Tangent Universe.

Collectively, these book inserts function much in the same way as superfluous voiceover would, insofar as they tell what the movie's already showing. It's worth mentioning that the very term "Tangent Universe," when applied to "Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut," seems to openly acknowledge how this cut allows for unnecessary tangents, working back in deleted scenes and making it explicitly clear what the movie is about.

Contrast this with the original "Donnie Darko," which is much more fair-handed in its distribution of clues that Donnie might simply be a paranoid schizophrenic, as his own hypnotherapist, Dr. Thurman (Katherine Ross), suggests. "The Director's Cut" makes a big change undermining this interpretation when it has Dr. Thurman reveal that Donnie's medication is a placebo, "just pills made out of water."

'Increased detachment from reality'

To really appreciate how "The Director's Cut" changes "Donnie Darko," it's helpful to remember just how much the original movie planted hints that Donnie might suffer from paranoid schizophrenia. When we first meet him, he's lying in the middle of the road in his pajamas, having sleepwalked (or rather, sleep-cycled) across town. We subsequently learn that he's off his medication, and the viewer has no reason to believe that Donnie's pills are placebos, since that revelation is absent from the original theatrical cut.

It contradicts some of the other information Dr. Thurman gives us, especially the part where she tells his parents, "Donnie's aggressive behavior, his increased detachment from reality, seems to stem from his inability to cope with the forces in the world he perceives to be threatening." She goes on to imply that the hallucinations he's experiencing (of a giant bunny rabbit named Frank, and liquid spears inspired by the water tentacle in "The Abyss") are "a common occurrence among paranoid schizophrenics."

Why would she keep giving him placebos even after she's suggested this? That's just one question that "Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut" opens up as it, too, shows an "increased detachment from reality." Conversely, the possibility of paranoid schizophrenia causing Donnie to hallucinate keeps the original movie grounded, offering up a more plausible, reality-based explanation than Frank's through-the-looking-glass question, "Do you believe in time travel?"

Donnie's sister, Samantha (Daveigh Chase) — who received her own messy spin-off sequel, "S. Darko" — interrupts one of his early conversations with Frank, walking in on him and bursting his bubble (and ours) with another question: "Who are you talking to?" Donnie replies, "I was just taking my pills," and it instantly throws into doubt the reality of what we've just witnessed.

'The search for God'

In the original "Donnie Darko," religion is more of a background shading. There's a scene where Dr. Thurman asks Donnie if he feels alone, and he gives a long answer, but it's not until she chimes in again that the dialogue clarifies they're talking about "the search for God" and feeling alone in the universe. "Donnie Darko: The Directors Cut" adds another moment where Dr. Thurman explains to Donnie the difference between an atheist and agnostic (he's the latter, she says).

At one point, we hear how Roberta Sparrow was a nun who left the church to teach science and write "The Philosophy of Time Travel." Yet were it not for the students' uniforms, some viewers might not even realize that Donnie, as The Atlantic observes, attends a Catholic school. In 2017, Richard Kelly told the site, "The search for God in science is perhaps the greatest quest of our species, and I like to tell stories about characters confronting God through these science-fiction mechanisms."

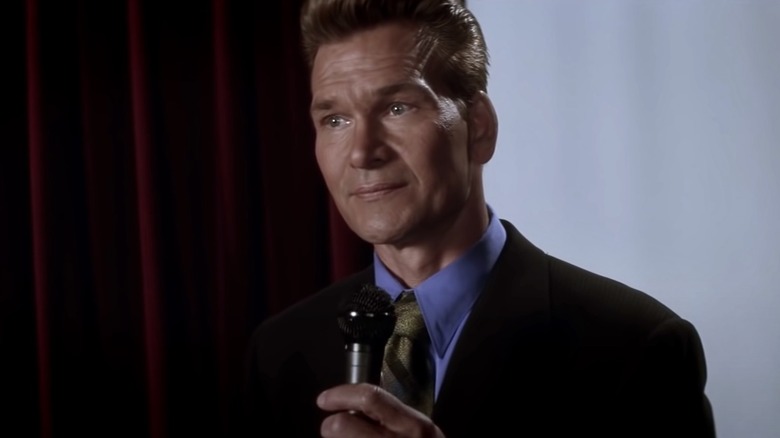

Like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, whose moonlit bike ride this movie evokes, Donnie Darko, the self-sacrificing teen with a superhero name, can be seen as something of a sci-fi Christ figure — as improbable and oxymoronic as that might sound. Despite his initials, this would surely make Jim Cunningham (Patrick Swayze), with his kiddie porn dungeon, "the Anti-Christ," as Donnie calls him.

When Donnie and Professor Monnitoff (Noah Wyle) are discussing "pre-formed destiny," Donnie talks about God controlling time and how a time traveler could theoretically avoid negating destiny by traveling "within God's channel." This is what Donnie does in the Tangent Universe, which is like the vision of earthly life that Willem Dafoe's Jesus has in "The Last Temptation of Christ" (a title that appears on the movie marquee behind Donnie).

'The dreams in which I'm dying'

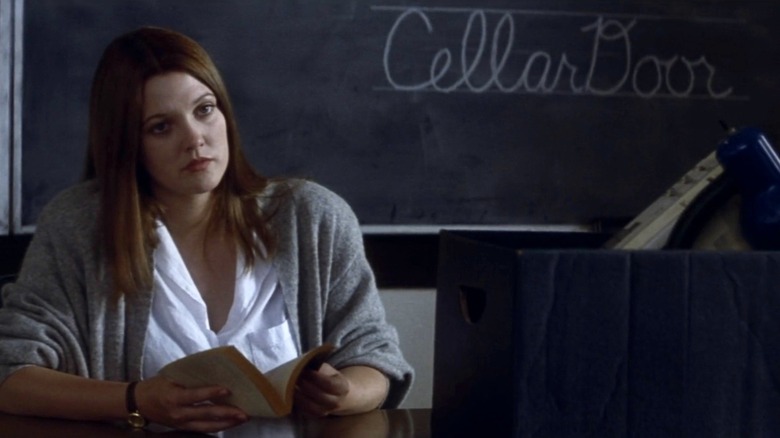

With one-liners like, "Sometimes I doubt your commitment to Sparkle Motion!" and, "Why are you wearing that stupid man suit?" "Donnie Darko" remains as quotable as ever. Drew Barrymore's final scene as Donnie's teacher, Ms. Pomeroy, popularized the idea that "cellar door" is the most beautiful phrase in the English language. In "The Director's Cut," Donnie reads a poem about Frank in her class, and she substitutes the rabbit-laden "Watership Down" for the outgoing Graham Greene book. Classroom discussion among hormonal teens about the breeding habits of rabbits ensues.

To be clear, the original "Donnie Darko" seeds in plenty of hints in favor of time travel or a time loop theory, such as Donnie's conversation with Professor Monnitoff about "a wormhole with an Einstein-Rosen Bridge" and how the vessel for time travel could be a "metal craft of any kind." There are also hints that Donnie's destiny and Frank are putting everything into place for him to fall into what "The Director's Cut" calls an "Ensurance Trap," whereby he will want to "go back in time and replace all those hours of pain and darkness."

Witness the cellar door that leads to Donnie's doom, and Grandma Death puttering out to the mailbox at just the right moment so that the car swerves to hit Gretchen. In the original movie, however, these coincidences are counter-balanced with suggestions of mental illness. The trauma of seeing Gretchen run down could just as easily cause Donnie to project his imaginary friend's face onto the driver who killed her. His final portal trip could be a break from reality, where he imagines himself dying to prevent tragedy, in accordance with the "Mad World" lyric: "The dreams in which I'm dying are the best I've ever had."

Ego reflections and attitudinal beliefs

There's a lot going on in "Donnie Darko"; it's one of those movies where you can watch it and rewatch it and notice new things every time. Even scenes of comic relief like the self-help video with a bed-wetter exclaiming "I'm not afraid anymore!" betray hidden meanings. Case in point: there's a line right before that where a "fear survivor" says, "I looked through the mirror, and in that image, I saw my ego reflection."

According to one theory— yet another interpretation "The Director's Cut" debunks — this is what Donnie does with his giant bunny rabbit friend, Frank. As that theory goes, maybe there is no Frank, and Donnie's just talking to himself in the mirror as he grapples with the terrible knowledge, imparted to him by Grandma Death, that "every living creature on earth dies alone." Given that Donnie is destined to save the universe ("The Director's Cut" calls him "The Living Receiver" instead of the Chosen One, but same difference), it seems more likely, in this interpretation, that Frank reflects Donnie's self-importance, rather than his Freudian ego, which would normally help govern a human being's inflated sense of worth as they reckon with their place in the cosmos.

Jim Cunningham, who gives seminars about "attitudinal beliefs," calls Donnie "a very troubled and confused young man." Though Donnie exposes the hypocrisy of Cunningham and conservative teacher Kitty Farmer (Beth Grant), his history of juvenile delinquency repeats itself when he burns down Cunningham's house. (It's revealed in dialogue beforehand that Donnie already burned down a house once before.)

Ultimately, accepting Donnie — and "The Director's Cut" itself — as the Chosen One may just serve to reflect one's own beliefs about the need for narrative clarity, and whether we're alone in the universe or have someone "watching over" us, like Donnie.

The Director's Cut is a 133-minute Tangent Universe

"Donnie Darko: The Director's Cut" is an interesting supplement to the first theatrical cut of the film, but its added scenes also interrupt the flow of the narrative and rob the movie of some of its mystery, spelling out in onscreen text what's happening through the pages of "The Philosophy of Time Travel." Ultimately, the original version of the film is a cult classic that's fine as-is, while the trajectory of Richard Kelly's career in the years since "Donnie Darko" leaves some room to question whether his directorial judgment is always the best.

After the critical and commercial failure of "Southland Tales" and "The Box" in the mid-to-late 2000s, Kelly went into a long hibernation, and while it's never too late for a comeback, he still hasn't made a movie since 2009. In 2021, when "Donnie Darko" was celebrating its 20th anniversary, /Film's Jack Giroux interviewed Kelly, who indicated that he has done uncredited writing work on other completed films in the intervening years, and that he has ten different scripts or projects of his own that are ready to go next in various stages.

Until one of those materializes, fans are left to revisit "Donnie Darko." It's been said that every filmmaker has at least one great movie in them; this was Kelly's. Perhaps the best way to reconcile his director's cut with the "Donnie Darko" viewers first fell in love with is to think of it as its own 133-minute Tangent Universe, not unlike the 28-day one Donnie visits. In the end, having seen what the Tangent Universe has to offer (which isn't always better), the audience is free to let it collapse in on itself and return to the Primary Universe of the original "Donnie Darko."