/Film's Top 100 Movies Of All Time

Making a list of the 100 greatest movies of all time is the definition of "damned if you do, damned if you don't." You're always going to leave something off. It's never going to feel complete. A particular genre, era, or filmmaker will be neglected. People are going to be mad at you no matter what, so why do such a thing?

Well, why climb Mount Everest? Because it is there. Because we must.

This isn't your list of the 100 best movies ever made. This is /Film's list of the 100 best movies ever made, as voted by a selection of writers and editors, with the final list determined via several hours of impassioned arguments and debates (which we recorded and you can listen to here and here). Those who participated were given simple instructions: Nominated films needed to be movies they truly love. Established canon should be thrown to the wayside, and obliterated if necessary. The movies you expect to be on a list like this shouldn't just waltz right in. Select, you know, your actual favorite movies.

The result is a list that we think is as exciting as it is maddening, a list composed of old and new masterpieces alike. We're proud that it covers areas lists like this often neglect (animation and horror, baby!) and annoyed by what it sidesteps (yes, it does skew a bit too Hollywood, we know). But one thing remains true above all else: This list was made honestly, and every movie on it is one the /Film team considers vital.

And now, in alphabetical order, here are the 100 best movies ever made. According to us. Your favorite movie is number 101. We promise.

12 Angry Men (1957)

Taking place essentially in real time, almost entirely in one room, and with a cast of characters who are almost all unnamed except for their juror numbers, Sidney Lumet's "12 Angry Men" is a masterclass in the push and pull of dialogue. As the jury gathers to convict an accused teenage murderer in what seems like an open-and-shut case, Henry Fonda's lone holdout — Juror #8 — suggests that they simply take an hour to talk things out. Tensions rise, prejudices are revealed, and human nature itself is put on trial. "12 Angry Men" is as gripping as any action film, set in an arena where words are the weapons that make the difference between life and death.

It's also a film that has only grown more relevant with time — particularly now, when opinion seems so deeply divided and factional that good faith debate seems impossible, and people changing their minds even more so. "12 Angry Men" delves deep into how opinions are formed, whether it's simply by following the crowd, or innermost resentments rising to the surface. And though the crime in question can't be solved in a jury room, there's a tinge of murder mystery to it that draws the viewer in, inviting them to become a thirteenth angry man.

The Alternate Take: In 2022, Sarah Polley delivered an answer to "12 Angry Men" with "Women Talking," the story of a group of Mennonite women who have only a day to resolve through the debate about what they should do in response to their colony's serial sexual assaults: do nothing, stay and fight, or leave. (Hannah Shaw-Williams)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

In his wry 1978 sci-fi comedy novel, author Douglas Adams tried to communicate the infinity of the cosmos: "Space is big. You just won't believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it's a long way down the road to the chemist's, but that's just peanuts to space."

What Stanley Kubrick's 1968 science fiction film "2001: A Space Odyssey" communicates best is the vastness of space and time. This is a film that begins millions of years ago when humans were still primates and ends in a heady space "Beyond the Infinite" where human consciousness and the fabric of spacetime begin to merge into one. "2001" is about the enormity of all things, and how the human race is only, just now, beginning to wrap our heads around it.

It's worth remembering that when Kubrick and his collaborator Arthur C. Clarke were constructing "A Space Odyssey," Earth was preoccupied with looking up. The United States and Russia were embroiled in a space race, and it seemed like the next step of human evolution — our movement into the stars — was immediately nigh. Traveling into space wasn't merely a feat of engineering, but a positive sign of humanity's ultimate fate as denizens of the cosmos. Our tools can kill, of course — whether it be a bone or a hyperintelligent computer named HAL — but they will lead us into the stars to meet beings we cannot understand. Only then will we be ready to be born.

The Alternate Take: If thinking of time as an enormous, interconnected fabric of human consciousness is your jam, then definitely try out Terrence Malick's "The Tree of Life" (2011). (Witney Seibold)

Alien (1979)

Depending on how you choose to look at it, "Alien" is either a ruthless statement on the gears of corporate capitalism chewing up and spitting out blue collar workers without remorse, an incisive commentary on sexual violence inflicted on a primarily male-dominated crew, or a straightforward sci-fi/horror flick that can be thoroughly enjoyed when taken exactly at face value. The true magic of this unparalleled movie isn't the wealth of fascinating concepts and provocative ideas present in Dan O'Bannon's screenplay, or the immediate influx of world-building provided by H.R. Giger's profoundly disturbing designs, or even how far director Ridley Scott elevated the production despite a minor budget. Instead, it's that all-too-rare feeling of a picture somehow exceeding the already-formidable sum of its parts.

As perhaps the peak example of "Less is more," this classic hails from a long-gone era when we were forced to reckon with the unknown hanging just on the edges of the frame. A derelict ship and a dead pilot carrying a mysterious alien cargo with no other explanation; a refreshingly practical crew of protagonists given no backstory or tragic origins to make them any more relatable than they already are; and a singularly terrifying villain that would provide nightmare fuel for entire generations of moviegoers for decades to come. "Alien" stands the test of time as the kind of horror that redefines a genre — a perfect organism.

The Alternate Take: After the stripped-down, functional brutality of "Alien," yet another Ridley Scott movie inspired a sequel exploring the extreme other end of the sci-fi spectrum. Where "Alien" embraced minimalism, "Blade Runner" and especially its follow-up set decades later, "Blade Runner 2049," leaned into their gaudy, noir, neon-lit trappings for all they were worth to delve into even more heady, existentialist themes — the fact that both franchises may or may not share continuity is only the cherry on top. (Jeremy Mathai)

All the President's Men (1976)

"The truth is these are not very bright guys, and things got out of hand." This blunt assessment of the men behind the Watergate break-in, spoken by Hal Holbrook's Deep Throat, will be the epitaph of the United States. We didn't know this when Alan J. Pakula's spellbinding dramatization of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein's pivotal role in hastening President Richard M. Nixon's resignation hit theaters in 1976. Pakula transforms recent history into a gripping paranoid thriller, while crafting a paean to the power of dogged journalism. It holds that when would-be despots take the White House, the country's fourth estate will instinctively hold these cretin's accountable.

Pakula wrings maximum suspense from Woodward and Bernstein's relentless digging. These men are so hellbent on piecing together the architecture of an inexplicable own-goal that they don't realize their lives are in jeopardy. Pakula wisely refuses to explicate the multitudinous conspiracy theories swirling around this incident and American politics in general. The story is getting the story, and getting it right. Robert Redford, Dustin Hoffman, Jason Robards, and Jack Warden inhabit their roles like they've been working the D.C. beat their entire lives. The victory is hard won, and the film ends as it began — with the gunshot blast of a typewriter hammer hitting paper. Democracy survives. At least, it did 49 years ago. Alas, the not-very-bright-guys run every institution of consequence today, including our free press. Pakula's film now resonates with the ache of a high-school yearbook. What a time that was.

The Alternate Take: The darkly manipulative power of the press is on full, cynical display in Billy Wilder's arsenic-laced "Ace in the Hole." Kirk Douglas' slimy journo is the anti-Woodward & Bernstein; rather than report the truth, he contorts it for his own professional/financial benefit. (Jeremy Smith)

Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy (2004)

Mainstream comedy was searching for an identity in the early 2000s in a post-"Scary Movie" world. One could argue that identity was found with 2004's "Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy," which served as the first mighty feature collaboration between "SNL" star Will Ferrell and director Adam McKay. Their first trip up to bat was a home run, even if critics of the day didn't see it that way. The absolute absurdist humor centered on Ferrel's Ron Burgundy as a newsman in the '70s struggling to get with the times, filled with non-sequitur gags and endlessly quotable lines such as "I'm in a glass case of emotion" or "60% of the time, it works every time."

This film would tee up the ball, not only for other Ferrell/McKay hits such as "Step-Brothers," but also comedies such as "The 40-Year-Old Virgin" that would further help give this era of studio comedy an identity it sorely needed. Well beyond its importance though, "Anchorman" plays like gangbusters as a laugh-a-minute, tight, singular motion picture experience. From all-time great names like Wes Mantooth (Vince Vaughn) to an all-timer of a silly performance from Steve Carell as Brick Tamland, this movie has aged like a big, tall glass of scotchy, scotch, scotch, cementing itself as not only one of the best comedies of all time, but one of the most important as well.

The Alternate Take: "Anchorman" owes a lot to "Caddyshack," a 1980 comedy about a different, very specific form of employment (caddying at a golf course) with a diverse cast of wacky characters featuring the who's who of comedy at the time. It's not a stretch to say that the Adam McKays or Judd Apatows of the world wouldn't exist without director Harold Ramis' seminal classic. (Ryan Scott)

Back to the Future (1985)

"Back to the Future" is perfect. Full stop. Director Robert Zemeckis gave audiences a crowd-pleasing motion picture that has a little bit of everything: a high concept sci-fi premise, some zany comedy, a dose of action and adventure, and even a bit of romance. With a brilliant, high strung, career-defining lead performance from Michael J. Fox as teen Marty McFly, a hilariously eccentric supporting turn from Christopher Lloyd as inventor Doc Brown, the adorable charm of Lea Thompson in an admittedly awkward family situation as Marty's mother, the social ineptitude of Crispin Glover as the clueless George McFly, and the unrivaled meathead douchebaggery of Tom F. Wilson as Biff, "Back to the Future" is filled with unforgettable characters, memorable quotes, and pure entertainment. We haven't even mentioned the fact that the DeLorean time machine is one of the most iconic props in cinema history.

How has "Back to the Future" endured after nearly 40 years? It's a flawless screenplay by Zemeckis and co-writer Bob Gale, one that stands as a sterling example of how to craft a rousing blockbuster. The structure of the story doesn't have a single set-up that doesn't pay off in a significant way. It's the cornerstone against which every other time travel movie is judged. Movies like this aren't often nominated for Academy Awards these days, but "Back to the Future" landed a nod for Best Original Screenplay, and honestly, it should have been nominated for Best Picture.

The Alternate Take: If you're looking for another example of a finely tuned screenplay turning into a masterful movie, look no further than "Tootsie," a comedy starring Dustin Hoffman as a struggling actor who finally finds gainful employment on a soap opera by pretending to be a woman. Funny and irresistibly charming, "Tootsie" is just a delight. (Ethan Anderton)

The Blair Witch Project (1999)

"In October of 1994, three student filmmakers disappeared in the woods near Burkittsville, Maryland while shooting a documentary. A year later their footage was found." So begins "The Blair Witch Project," the 1999 found footage horror film that became a cultural phenomenon. Thanks to some clever marketing that sold this tale of terror as 100% real — complete with "MISSING" posters for its three lead actors — "The Blair Witch Project" was a massive box office success, scaring up $248.6 million against a shoestring budget. Filmmakers Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez came up with a simple but effective concept: a faux documentary about three film students — Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard, all using their real names — who venture into the Maryland woods to make a doc about the legend of a local witch. Sure enough, these three hapless kids get lost in the woods and quickly learn that the so-called Blair Witch is more than a legend.

There was so much hype surrounding the film that a backlash was inevitable, and sure enough, many viewers took issue with the film's shaky camera work and the fact that you never really see anything in the film, although that's not quite true — you see plenty, it's just done in a subtle way that doesn't quite announce itself, which makes things all the more frightening. But it's a testament to how effective this film is that even after its release, many still thought it was completely real and that the three leads were really missing and presumed dead.

Dread hangs over the film from the start, and the grainy footage only adds to the unsettling vibe. This feels real, and when the supernatural stuff starts happening, that feels real, too. By the time the film reaches its terrifying climax, all hope is lost, and only the legend remains.

The Alternate Take: "The Blair Witch Project" ushered in a new era of found-footage horror films, many of which just don't cut it. But one of the best of the best is Joel Anderson's "Lake Mungo," a faux documentary about a family that swears their dead daughter is haunting their house. Thick with ominous dread, "Lake Mungo" ends up being a treatise on death itself, and how it's coming for all of us sooner or later. (Chris Evangelista)

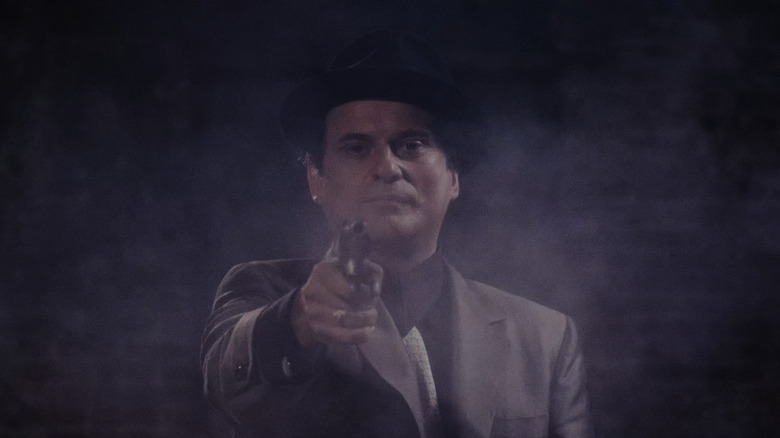

Blow Out (1981)

The paranoid style transmogrified into personal tragedy. Brian De Palma blends the buckshot satire of his early comedies with his precision-crafted suspense films and comes away with a work that's as brutally cynical as it is heartbreaking. John Travolta stars as a bored sound man whose work leads him to witness and record a fatal car crash involving a top presidential candidate. When he pieces his sound together with a Zapruder-like presentation of the accident, he becomes convinced that the blown tire was shot out by a hidden gunman.

De Palma tones down the eroticism of "Dressed to Kill" to vent his frustration with the house-wins rules of political cover-ups, particularly the JFK assassination. Travolta's character, desperate to atone for a lethal mistake from his past, believes he can expose the plot, and he's capable enough to get us believing in him. De Palma hooks us with dense technical details, and gets first-rate performances out of his leads. Karen Allen works an adorable riff on Shirley MacLaine's perky "Some Came Running" wastrel, while John Lithgow horrifies as a hitman turned serial killer. De Palma expertly tightens the screws before walloping us with a corker of an ending. It's his finest hour as a filmmaker.

The Alternate take: Rebecca Romijn sizzles as a diamond thief who double-crosses her accomplices in De Palma's wildly underrated "Femme Fatale." It's an erotic fever dream, and, like "Blow Out," the purest of pure cinema. (Jeremy Smith)

Brazil (1985)

Director Terry Gilliam's "Brazil," a portrait of a sci-fi dystopia dominated by cruel and casual fascism, infuriating bureaucracy, and a population too comfortable to do a damn thing about it, has aged like a wine you wish didn't taste so familiar. The film's grim comedy is matched only by its sweeping eye for romance and beauty in the face of oppression — what can save us from a nightmare if not a beautiful dream?

With a cast of game actors leading the charge (including Michael Palin playing against type as a disturbing family man with a successful career as a government torturer), Gilliam's film borrows the rib-jabbing satire of his Monty Python days but instills it with an anger that resonates, all brought to life with a camera whose mobility reflects the chaos and confusion of the world it depicts. And that world, cluttered and ugly and gray and utilitarian to the point of suffocation, remains one of the great cinematic landscapes, one that fascinates and sickens in equal measure.

Gilliam famously fought the studio to preserve his vision, pessimistic ending and all. But the real miracle of "Brazil" is that the movie itself is better than the story of its making. And that's one of the most interesting stories in Hollywood history, so that's saying something.

The Alternate Take: For a less intentionally idiotic and more beautiful and haunting vision of a science fiction dystopia that hits far too close to home, you can't go wrong with Ridley Scott's immortal "Blade Runner." (Jacob Hall)

The Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

James Whale's brilliant, groundbreaking, haunting "Frankenstein" feels almost quaint compared to his energized and subversive follow-up. "The Bride of Frankenstein" finds the Monster, played from living corpse to childlike naiveté to tortured adulthood by the iconic Boris Karloff, growing beyond his creator's horrified dreams, and longing for a creature just like him to ease his lonely, man-made soul. Meanwhile, the guilt-ridden Doctor Frankenstein (Colin Clive) finds himself goaded into recreating his ill-fated experiment by an old college... friend... named Doctor Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger), who laughs in the face of normativity and toasts "a new world of gods and monsters."

"The Bride of Frankenstein" abounds with innovative visual effects, eerie makeup, stunning cinematography. It takes Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's literary masterpiece and adapts it into ecstatic cinema, keeping all the horror, but adding new layers of camp, and all the while needling at social convention. Religion, sexuality, and morbidity of the weirdest kind. To watch "The Bride of Frankenstein" today is to wonder at how Whale ever got away with it amidst the constrictive morals of the Hayes Code, and to marvel at just how fresh and bizarre it all still is. The early horror films from Whale — two "Frankensteins," the ingenious "The Invisible Man," and the wonderfully bizarre "The Old Dark House" — make up one of the genre's great oeuvres, and "Bride" is the masterpiece.

The Alternate Take: Did somebody say "religion, sexuality, and morbidity of the weirdest kind?" Ken Russell's endlessly controversial and deliriously fascinating "The Devils" (1971) couldn't be described better. The film's perverse yet pointed exploration of nuns claiming to be possessed by sexually-depraved demons in the 17th century has the power to get under anyone's skin, and it loves to squirm around in there. (William Bibbiani)

Casablanca (1942)

The astonishing thing about Michael Curtiz's "Casablanca" is that, despite being removed from modern sensibilities by 81 years, it still plays like the Devil. Curtiz, a Hungarian-born director who had made hundreds of films all over the world prior to "Casablanca," was known in America for making action pictures like "Captain Blood" and "The Adventures of Robin Hood." His propensity for action and pacing allowed "Casablanca" to emerge as a feisty, energetic romance, full of intrigue and melodrama, without ever feeling artificial or contrived. Humphrey Bogart's embittered WWII bar owner Rick has become something of a Jungian archetype, while Claude Rains' Renault, comfortable with his corruption, remains one of cinema's great scoundrels.

"Casablanca," despite its status as a classic, was constructed as "just another studio film" by Warner Bros. It had some contract stars, and was tapping into popular trends at the time: romance, exotic locations, spy-type intrigue, and concerns about World War II. It seems that sometimes, through strange ineffable alchemy, the studio system can produce an indelible and timeless classic kind of by accident. Just this once, everything fell into place. The drama is beautiful, the romance is moving, the politics are assertive, the characters sublime. Even "As Time Goes By," written for the movie to sound like an old standard has, in itself, become an old standard.

The Alternate Take: If Curtiz's career as a genre filmmaker interests you, one would do well to check his 1932 horror mystery "Doctor X," a film shot in then-new color techniques and featuring a murder mystery wherein all the suspects are mad scientists. It's dynamic, fast-paced, and exciting. It's like a sci-fi noir version of the play-within-a-play segment of "Hamlet." (Witney Seibold)

Children of Men (2006)

"Children of Men" is a harrowing experience that lets its audience know that nothing is safe from its first scene, when former activist Theo (Clive Owen) narrowly escapes a terrorist bombing in a coffee shop. Alfonso Cuarón's brutal-but-hopeful dystopian masterpiece has it all: Christian virgin birth allegory, harsh commentary on nationalism and racism, and some of the most heart-pounding action sequences ever put to film. The film is a carefully orchestrated symphony that uses silence like a weapon, where even moments that might feel like a reprieve in other films are still menacing and tense.

The movie takes place in a world where no babies have been born for 18 years, but a young refugee woman named Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey) is trying to find asylum in London, and she's miraculously pregnant. The problem is that refugees are treated as less than human, and there's a good chance her baby would be taken away from her (and possibly even killed). Theo, along with his ex-wife Julian (Julianne Moore), and their allies from their activism days, are tasked with getting Kee to the coast and on a boat, where she will be taken to safety. Cuarón and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki utilize an always-moving camera, even inventing a masterful rig specifically for an intense one-take sequence during a violent car chase that feels more intimate than even documentary filmmaking. "Children of Men" is incredibly made, and sadly only grows more relevant as time goes on.

The Alternate Take: For another thought-provoking dystopian story with bold cinematography, look no further than Terry Gilliam's 1996 film "12 Monkeys," starring Bruce Willis as a prisoner tasked with time-traveling to prevent an apocalyptic plague unleashed by terrorists. (Danielle Ryan)

Citizen Kane (1941)

The greatness of Orson Welles's directorial debut has been so widely accepted, and for so long, that putting it on a list of the greatest movies ever made might seem like a cliché. But "Citizen Kane" is no stuffy art house venture. Indeed, Welles's youthful enthusiasm, his eagerness to push boundaries, and his desperate desire to entertain keeps this classic timeless. The 25-year-old wunderkind throws everything at his audience to keep our attention rapt, injecting a serious indictment of American capitalism — in which a young impoverished boy gets raised by a corporate tycoon, and tries to fill the void in his soul with a lifetime of empty acquisitions and superficial victories — with humor, music and Shakespearean melodrama.

"Citizen Kane" is such a lively and impassioned affair that its many subtleties aren't visible without multiple viewings, they're too buried under exciting camerawork and crackling dialogue. Even the film's famous ending — there's no sense in spoiling it here — takes on new dimensions, when you realize only in retrospect how close "Rosebud" was to Charles Foster Kane all along, what distracted him from his pursuit of it, and what it ultimately meant to him beyond the obvious, yet no less tragic interpretation offered by the film's stunning final moments.

The Alternate Take: Orson Welles rewrote the cinematic language when he was 25, with a film that's been called the best ever made. How fitting, then, that the most recent film to grab that title — Chantal Akerman's "Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles" (1975) — was also the work of a 25-year-old genius, challenging cinematic norms as she took the seemingly mundane life of a stay-at-home mom and sex worker and transformed it into the audience's whole universe, to the extent that even subtlest changes in routine become gigantic and powerful. (William Bibbiani)

Clueless (1995)

The pantheon of teen cinema exists in two timelines: Before "Clueless," and after. Amy Heckerling's updated adaptation of Jane Austen's "Emma" impacted fashion, language, pop culture, and cinema forever. This "way existential" piece is a slice-of-life comedy centered on ultra-rich Beverly Hills teenagers, but beneath the seemingly vapid and shallow exterior is a deeply layered story not just about growing up, but embracing a life of self-aware maturity. Alicia Silverstone's Cher Horowitz is an all-time feminist protagonist, banishing the misogynistic idea that being a smart and respectable woman requires disavowing stereotypical feminine behaviors or expressions.

At the same time, "Clueless" is a brilliant satire on white, wealthy elites. Heckerling embraces the smart rom-com beats of Austen's literary work, and uses Cher and her friends as a vehicle to point out the ways folks who already "have it made" still have a lot of growing up to do.

Cher may be the central focus, but "Clueless" is ultimately a story about the power and necessity of female friendships, and how women are at their best and brightest when working together and learning from one another, rather than trying to teach each other down the way society wishes we would. It's only when Cher, Dionne (Stacey Dash), and Tai (Brittany Murphy) stop trying to fall in line with the arbitrary societal requirements of high school and instead do what truly makes them happy that they're able to feel less clueless about what comes next.

The Alternate Take: "Heathers" (1988) completely changed the landscape of teen cinema, a pitch-black comedic satire unafraid to acknowledge the mortifying realities of teenage existence with just as many quotable lines. How very, indeed. (BJ Colangelo)

Coraline (2009)

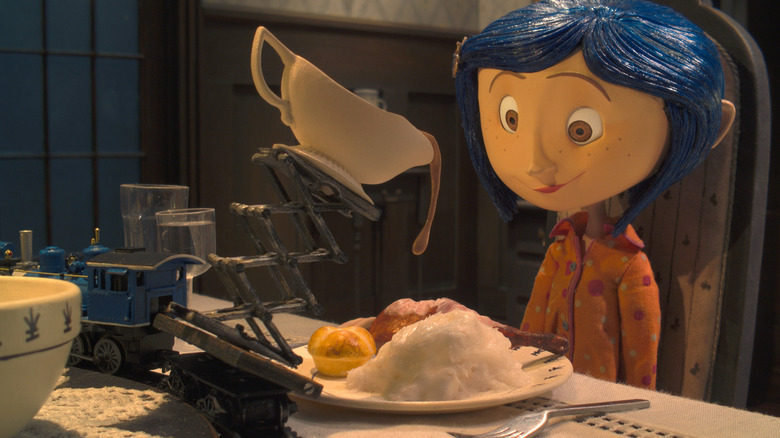

Leave it to the twisted mind of Henry Selick to do justice to Neil Gaiman's writing on the big screen. Selick's "Coraline" is the rare movie to fully capture the delicate mixture of terror, whimsy, and poignancy that characterizes Gaiman's literature. It also suggests that animation might be the ideal medium for adapting the multihyphenate's work. Gaiman's stories tend to morph from one genre to another in the blink of an eye and "Coraline" is no exception. But Selick's film never struggles to maintain the pace, its ever-moldable and gorgeous stop-motion animation shifting through a spellbinding array of colors and shapes to match every twist and turn in its narrative.

Speaking of, there are few modern animated movies quite as tightly-structured as "Coraline." Nary a scene nor interaction fails to move the story forward or develop its characters in some meaningful way, even when it's simply Coraline herself (Dakota Fanning channeling her inner moody tween to perfection) moping about her family's new apartment. At its core, though, Selick's film is more than just an extra-scary coming-of-age fantasy in the style of "The Wizard of Oz." It's a movie that teaches kids that adulthood is not actually something to be afraid of, while at the same time reminding grown-ups what the world looks like through the eyes of a child. And what better way to impart those lessons than a movie that will mildly traumatize the kiddos of the world?

The Alternate Take: 30 years (and counting) after its release, Selick's "The Nightmare Before Christmas" remains a fiendish holiday delight. But beneath Danny Elfman's cheerfully macabre tunes and the movie's gorgeously warped stop-motion visuals is a timeless reminder: Even the Pumpkin King struggles with ennui and creative burnout every now and then. (Sandy Schaefer)

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

"Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" is more than just the best Ang Lee film, it's also the most Ang Lee film. Thematically, Lee's Wuxia epic cuts to the heart of the director's electric filmography, exploring the ways repressed desires and emotional subjugation — most of which is imposed by social practices — wreak havoc on people's lives. It's what makes "Crouching Tiger" so deeply romantic yet at the same time melancholic. So much of the movie's conflict and eventual tragedy might have been avoided, had its characters not been forced into the boxes deemed appropriate for them by society (be it because of their gender, class, or lifestyle).

The other defining quality of Lee's artistry is his knack for pushing the envelope technically — and in that regard, "Crouching Tiger" soars higher than two martial artists clashing swords over the treetops of a bamboo forest. Working in tandem with cinematographer Peter Pau, legendary Hong Kong fight choreographer Yuen Woo-ping, and the rest of his cast and crew, Lee crafts some of the most breathtaking martial arts brawls in cinema history. Decades later, the film's gorgeous real-world locations and awe-inspiring practical effects retain their power, and yet it's the combination of spectacle and its unique perspective on the Wuxia genre's motifs that give the movie its true staying power.

The Alternate Take: Substitute the martial arts sequences in "Crouching Tiger" with delectable foodie porn and the action-adventure story with a plot involving a widower and his daughters, and what do you get? Ang Lee's thoroughly captivating 1994 romantic dramedy "Eat Drink Man Woman," a must-see for anyone who enjoys the filmmaker's work. (Sandy Schaefer)

The Dark Knight (2008)

If any popular filmmaker of the 2000s has a shot at making their way onto the eventual Mount Rushmore of cinema, it is almost certainly Christopher Nolan. Much of that has to do with his originals such as "The Prestige" and "Inception," yes, but it's the man's work with one of the biggest pop culture icons of all-time that cements his status as a legend behind the camera. "The Dark Knight" picked up where "Batman Begins" left off, but that first film only teed up the ball for something far greater — one of the greatest comic book movies ever made. Period.

With a great deal in common with expert crime dramas such as "Heat," Christian Bale's second solo "Batman" film feels so grounded and real (especially compared to the camp of "Batman & Robin," released just over a decade earlier) that it hardly feels like a superhero movie in the traditional sense at all. From the opening frames of the bank robbery to the film's superheroic closing moments where Batman becomes the hero we all understand him to be, this is what all summer blockbusters wish they could be. The entire thing is elevated by the late Heath Ledger as The Joker, which easily ranks as one of the most memorable performances ever committed to film. If there's ever been a case that comic book movies can and should be taken seriously, this is it.

The Alternate Take: 2008, as it turns out, is the most significant year in the history of making superhero movies an ongoing, cinematic concern. Case in point, "Iron Man" was also released that year, which launched the Marvel Cinematic Universe by turning a B-list hero into an A-class comic book movie. Remarkable that these movies were released within mere weeks of one another. (Ryan Scott)

Die Hard (1988)

There is a convincing argument that great cinema does not require perfection. So many of the best movies ever made (many of them on this list) have their flaws. But every so often, a movie does come our way that is downright perfect no matter how one slices it. One of those movies is "Die Hard," the action classic to top all action classics, not to mention one hell of a Christmas movie. This is Bruce Willis at his finest, working under the direction of the brilliant John McTiernan. It's deceptively simple yet brilliantly executed, centered on a bunch of vaguely European criminals who just want a bunch of money with one rogue cop standing in their way. That's cinema, baby.

When the greatest movie villains of all time list is put together — be it on this site or elsewhere — "Die Hard" belongs in the conversation. But part of what makes this movie stand out is the sheer perfection of Alan Rickman as Gruber. From the moment he enters Nakatomi Plaza to the moment he falls from the top of that glorious building, it's everything we popcorn-loving moviegoers yearn for. Endlessly quotable lines, relentless re-watchability, and unabashed entertainment of the highest order, "Die Hard" is what all action movies aspire to be.

The Alternate Take: For those who love this brand of action, McTiernan had arguably the greatest three-movie run in history, following up "Die Hard" with "The Hunt for Red October." But that run started with another all-timer in the form of 1987's "Predator," which helped cement Arnold Schwarzenegger as an action star who had more than one trick up his sleeve. Another beautiful marriage of the right star with a brilliant premise that is just as deserving of immortal status. (Ryan Scott)

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Watching Sidney Lumet's beautiful and blistering 1975 film about a bank robbery gone wrong feels a bit like stepping on a live wire for 125 minutes straight. This is a film that jolts audiences from our stupor as well now as it did upon release, thanks to a stunning performance by a young Al Pacino, a funny, dark, and melancholy script from "Cool Hand Luke" scribe Frank Pierson, and a ripped-from-the-headlines true story.

"Dog Day Afternoon" pulls from the real life of John Wojtowicz, a man who, according to the Life magazine piece on which the script was based, held up a bank in 1972 in order to help pay for his transgender girlfriend's gender-affirming surgery. The film's subjects would eventually sue the project for its inaccuracies, but there's certainly an emotional truth to "Dog Day Afternoon" that transcends its true story moniker. Pacino's volatile yet charming performance as Sonny Wortzik is countered perfectly by a rare appearance from John Cazale, whose robbery accomplice Salvatore Naturile may be the most tragic character in a film that's full of them. With sympathetic criminals and overtly queer characters at its core, "Dog Day Afternoon" is a transgressive and unforgettable anti-authority shout of a film.

The Alternate Take: 1976's "Network" is the other half of Lumet's mid-'70s cinematic one-two punch, and it's just as classic as "Dog Day Afternoon." "Network" features another American man on the brink, only this time around, it's Peter Finch's fed-up TV news anchor Howard Beale. (Valerie Ettenhofer)

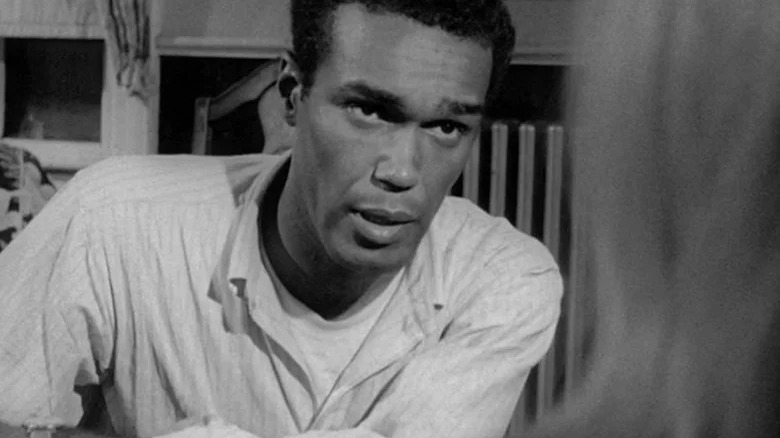

Do the Right Thing (1989)

It's well established that Spike Lee's sizzling-day-in-the-life of a block in Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood is the definitive cinematic depiction of race relations in this busted country, but people often overlook how entertaining and downright joyous it is for most of its runtime. For some urban dwellers, this was a rare opportunity to see themselves on screen in all their festive, loving, good-naturedly quarreling glory. Every community has a Da Mayor (Ossie Davis) or a Mother Sister (Ruby Dee), and there's always some middle-aged men hanging out, sucking down suds and talking trash on a hot summer day. Lee's Bed-Stuy isn't a paradise, but it's a place where people who've grown up knowing each other tend to take care of each other when s*** goes down.

At the center of the drama is Sal's Famous Pizzeria, and the conflict that explodes out of this establishment is depicted without a clear slant. Lee wisely leaves his audience to draw their own conclusions about the dispute between Sal (Danny Aiello), Buggin' Out (Giancarlo Esposito) and Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), but he makes it plain that the most intrusive, destabilizing force in the neighborhood is the police. The conclusion is tragic and infuriatingly unnecessary, and a reminder that cops who patrol an area where they do not live take an antagonistic approach to the people they are supposed to protect. This element of Lee's film feels more searingly palpable in 2023, and makes his masterpiece more essential than ever.

The Alternative Take: Lee's "Malcolm X" is, like "Do the Right Thing," as entertaining as it is provocative. He gets an all-time great performance out of Denzel Washington as the slain religious leader, and humanizes a man who, for too long, was viewed as a fire-breathing demagogue. (Jeremy Smith)

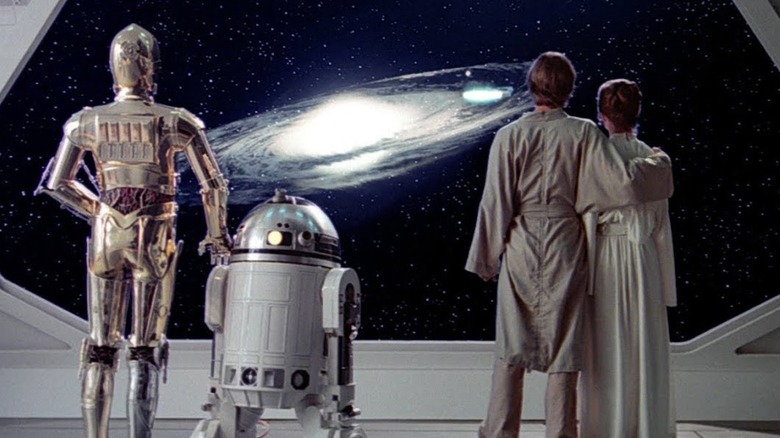

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

"Star Wars" changed American movies forever, but "The Empire Strikes Back" is the reason the franchise is still thriving today. Lawrence Kasdan's crackerjack screenplay supplies Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) with lively banter that would be right at home in a screwball comedy. It also, miraculously, downshifts to imbue the Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) and Yoda relationship with a Buddhist spirituality. The stakes are gently raised as we invest in Han and Leia's blossoming romance and the deeper meaning of The Force. Who knew that a giggly, green, 2'2" puppet would get a generation of young moviegoers considering their life's purpose?

Of course, when it comes to action, "The Empire Strikes Back" has it where it counts. The Hoth battle, with T-47 airspeeders buzzing AT-AT walkers is thrilling stuff, as is the Millennium Falcon's frantic flight through a dense asteroid belt. It all builds to a masterfully orchestrated feat of parallel action on Cloud City, where Leia and company scramble to escape the clutches of the Empire, while Luke takes his first crack at Darth Vader (and learns something awfully disquieting about his heritage in the process). Audiences freaked out over the cliffhanger finale, but that didn't stop them from lining up time and again to compile intel on where the concluding installment might be headed. This is the apex of the franchise, and it still hasn't been topped (though Rian Johnson got awfully close).

The Alternate take: George Lucas handed Irvin Kershner the reins on "The Empire Strikes Back" based on the director's spooky thriller "Eyes of Laura Mars." Written by John Carpenter, it's a nifty, high-style American giallo wherein fashion photographer Faye Dunaway envisions a killer's acts as they happen. (Jeremy Smith)

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Over a long career spent assembling deeply personal stories in crowd-pleasing packages, "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial" is still Steven Spielberg's most emotionally naked work. It's a film that taps deeply (even painfully) into the universal experience of being a lonely child who's hurt and confused to learn that life doesn't always go the way we would like. It might be an other-worldly visitor with a magic touch who teaches Elliott the power of empathy and compassion for others, yet it's the film's fantastical elements that free up Spielberg and writer Melissa Mathison to deal with harder emotional truths as authentically as they do.

Framing is also key to the power of the movie's story. Spielberg meticulously films "E.T." from the perspective of a child, presenting most of the adult characters as blurry figures or, during a particularly harrowing moment, as faceless beings invading Elliott's home. This emboldens "E.T." to run the gamut in terms of its tone, shifting effortlessly from scenes of terror and heartbreak to whimsical comedy and the ebullient wonder of the iconic flying bicycle rides (fueled by John Williams' stirring and wondrous score). It's the type of pure, unrestrained cinematic magic that the very term "Spielbergian" has come to encompass.

The Alternate Take: Who could've predicted Spielberg would see so much of his own life in the true(-ish) tale of a runaway teen con artist? "Catch Me If You Can" is brisk and amusingly risqué for a Spielberg film, but it's the affecting story of a kid yearning to repair their broken family that makes this one of the director's essential offerings. (Sandy Schaefer)

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Director Michel Gondry brings his makeshift moviemaking mind to this lo-fi sci-fi romance starring Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet as two star-crossed lovers. Well, maybe. It depends on how you look at it this magnificent motion picture. Either the melancholy Joel (Carrey) and the impulsive Clementine (Winslet) are doomed to repeat a failed romance for the rest of their lives, even after they have any memory of each other erased from their minds, or they're destined to be together, no matter how many times they screw it up. That's part of the undeniable beauty of "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind." Either it's a tragic reminder of the relationships that fall apart or an encouraging reminder that true love will endure.

What makes "Eternal Sunshine" even more special is the practical camera tricks and visual effects used to bring the story to life. Our story cuts back and forth between present day and memories of the past in reverse chronological order as two technicians erase the memory of Clementine from Joel's memory. As each memory is erased, Joel realizes he doesn't want to forget about Clem, and we watch him desperately try to hold onto as much as he can, even as the memories crumble around him. The way Gondry brings such a grand concept to life in a deceptively simple way is just good old fashioned creative filmmaking, and everything comes together to make this movie a masterpiece.

The Alternate Take: Much of the same grounded, surreal filmmaking style and quirky storytelling that makes "Eternal Sunshine" so great can also be seen in "Being John Malkovich," which makes sense since both were written by acclaimed writer Charlie Kaufman. It's more of a dark comedy than "Eternal Sunshine," but it's a stellar, original piece of cinema. (Ethan Anderton)

The Exorcist (1973)

Just five years after the Hays Code and its strict rules of self-censorship lost its grip on film industry, Regan MacNeil was bloodily using a crucifix in a deeply inappropriate manner as the demon possessing her screamed uniquely blasphemies and her mother watched in horror. You could say it was quite a transformative time for Hollywood.

That sheer, unrestrained depravity and malevolence are a big part of what makes "The Exorcist" such a terrifying film: once it smashes through those boundaries, the audience has no idea where the guardrails are — or if they even exist at all. Fear is often dismissed as a cheap emotion that's easy to wring from audiences, but it takes a lot of skill to make a film as relentlessly terrifying as this one. The initial slow build of dread lulls you into expecting a slow burn suspense, until "The Exorcist" starts to hit you with stings of chaos, monstrosity, and blasphemy extreme enough to shock even the staunchest atheist.

There is a lot of depth to "The Exorcist," underpinning the green projectile vomit and those sneak-attack glimpses of Captain Howdy. Ultimately, though, its place in the top 100 is earned simply because few films have ever scared so many pants off so many people.

The Alternate Take: If another movie were to make it into this list by sheer virtue of leaving audiences too frightened to move, it would have to be "Ju-On: The Grudge." There really isn't much of a plot — it's a movie where a series of people go to the same house and see a horrible thing — and yet with the simplest of set-ups director Takashi Shimizu delivers a masterclass in crafting horror. (Hannah Shaw-Williams)

Get Out (2017)

With some movies, it can take years of reevaluation and evolving mindsets to finally recognize what a certain filmmaker — typically considered to be "ahead of their time" — was trying to accomplish. With others, you just know an instant classic the minute you see it. Jordan Peele's feature debut "Get Out" belongs to a highly specific class of movie that stands out because of how precisely and unapologetically it remains of its time. Releasing in theaters barely a month after Donald Trump's inauguration, the circumstances of the movie's timing clearly enhanced the power of its themes — although even that would mean little if it weren't for the technical precision Peele demonstrates behind the camera, too.

Every choice in "Get Out" is made in service of putting audiences in the perspective of a Black man living in America, under systemic racism both insidiously subtle and obviously violent. For much of the story, the film's main antagonist is embodied by Bradley Whitford's Dean Armitage, a well-meaning white liberal father lacking in self-awareness. After the big reveal, Daniel Kaluuya's Chris Washington must reckon with the lingering effects of the oldest and most deep-rooted example of racial bigotry in American history. "Get Out" starts with a Black man lost and kidnapped in a wealthy white neighborhood. It ends by successfully convincing even its white viewers to share the same dread that its Black main character feels when flashing police lights arrive at the most inopportune moment. That's movie magic, baby.

The Alternate Take: From one modern horror movie acting as a feature-length metaphor for complex social realities to another, Leigh Whannell's "The Invisible Man" bears the distinction of somehow managing to remix a familiar property into something shockingly relevant, turning a classic Universal monster story into a parable about abusive relationships and gaslighting. Like "Get Out," its potent themes are matched by the razor-sharp script and filmmaking acumen that combine to make each scare land, squeeze every ounce of tension out of the story, and leave viewers thrilled and horrified by the carnage left in its wake. (Jeremy Mathai)

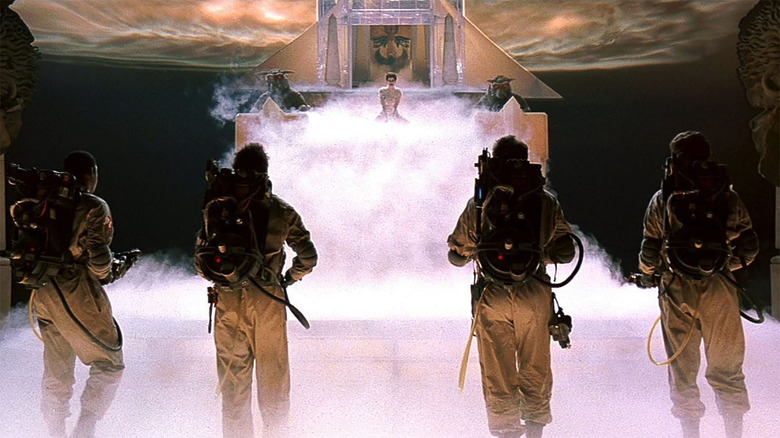

Ghostbusters (1984)

Who ya gonna call? Immediately knowing the answer to that question may be enough to solidify "Ghostbusters" as one of the greatest movies of all time. Powered by one of the most famous movie theme songs of all time, "Ghosbusters" is more than your average comedy. Director Ivan Reitman delivered a gamechanger by combining the sarcastic wit of comedy legends Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, and Harold Ramis with a blockbuster premise, making for a new kind of cinematic experience back in 1984.

Rarely had this level of laugh out loud humor been paired with earnest genre filmmaking on this large of a scale. While the buddy cop subgenre had achieved a similar feat in the blending of gunfire and car chases with big laughs, the VFX-driven paranormal spooks, specters, and ghosts at the center of "Ghostbusters" turn it into something else entirely, giving us a wry, blue collar approach to an apocalyptic threat in the heart of New York City. The film goes from sliming Bill Murray and calling an EPA agent d***less to fending off a destructive god and a massive marshmallow man. It doesn't get much better than this. In fact, many movies have tried to capture the undeniable magic of "Ghostbusters," but even the franchise itself couldn't capture lightning in a ghost trap again with "Ghostbusters II."

The Alternate Take: If there's one movie that manages to capture the same comedic spirit of "Ghostbusters" while also maintaining the blockbuster scale, it's "Men in Black," featuring the unlikely fantastic teaming of Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones and the unparalleled movie magic of special effects master Rick Baker. (Ethan Anderton)

The Godfather (1972)

"That's my family, Kay. It's not me." Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) means this at the outset of Francis Ford Coppola's mafia epic, but their blood is the thickest of thick. Marlon Brando's disappearing act as Don Vito Corleone was the hook that had moviegoers circling blocks on opening weekend, but the central tragedy of "The Godfather" is Michael's transformation from war hero to cold-hearted kingpin. He surrenders his future to avenge an attempt on his father's life, and, after a grave personal tragedy, returns from Sicily a man of unrepentantly corrupt industry. He is the apotheosis of a corporate operator in that the family business condones murder as a means to a perpetuating end. This is how Vito gained a foothold in America, and Michael, having killed for his country, is shockingly comfortable with the bloodletting aspect of his chosen profession.

This was a make-or-break movie for Coppola, and he did himself no favors by hiring Gordon Willis to shoot the film in shadowy earth tones. But this dimly lit gambit, abetted by Nino Rota's mournful main theme, imbued Mario Puzo's pulpy narrative with a dark soul. The casting is top-to-bottom perfection, and Coppola's mise-en-scène is a literal master class (his staging is taught in film schools all over the world). "The Godfather" is every bit as captivating as it was 51 years ago. It is as timeless as "The Wizard of Oz" and "Casablanca." You're throwing it on right now, aren't you?

The Alternate Take: "The Godfather" and "The Godfather Part II" are masterpieces in their own right, but the ideal version of Coppola's first two installments might be found in "The Godfather Saga." The chronological telling of the Corleones' story threads both movies together, and sticks that Lake Tahoe ending like a knife through the heart. (Jeremy Smith)

Goodfellas (1990)

Martin Scorsese's masterpiece, "Goodfellas" is an endlessly rewatchable look at three decades of life in the mafia as viewed through the eyes of Henry Hill (Ray Liotta). Based on a true story, we follow Hill as he grows up around and eventually becomes a gangster, guided by local hoodlum Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro, who has never been cooler than he is in this movie) and pal Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci in an Oscar-winning role).

Scorsese weaves a rich tapestry here, focusing on tiny details that burn themselves into our minds — the pinky rings, the silk suits, the bad jokes, the dimly lit nightclubs, the bursts of violence, and of course, the food. So much food. (Don't forget to stir the sauce!)

Slick, stylish, and hilarious, Scorsese's film looks like it's glorifying a life of crime — until it all comes crashing down in a coke-fueled, murder-filled haze. Henry is not a big name in the mafia, he's a low-level crook who just happens to be our Dante, guiding us through several circles of hell. Using a showstopping one-take, brutal violence, a darkly comedic script, a soundtrack full of wall-to-wall pop music, and an energy that absolutely no one has ever been able to recreate (except for Scorsese), "Goodfellas" is brilliant, nasty, and one of a kind. The fact that it lost Best Picture at the Oscars to Kevin Costner's hum-drum "Dances With Wolves" should be considered a crime against cinema.

The Alternate Take: "Goodfellas" is a young man's look at a life of crime. Decades later, Scorsese created a much different gangster movie with "The Irishman," bringing back "Goodfellas" stars De Niro and Pesci and adding Al Pacino to tell a winter's tale — a story of violent men who slowly watch the world pass them by until they're irrelevant bones in a box. A massive, staggering work, this is one of Scorsese's best pictures, and the fact that he made it so late in his career is a testament to his power. (Chris Evangelista)

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966)

It's almost funny that Sergio Leone considered "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly" a satire of Hollywood westerns because, in hindsight, the film is more of a reconstruction than a deconstruction. Just a year before the similarly transgressive "Bonnie and Clyde" kicked off the New Hollywood era in earnest, the sheer power of Leone's filmmaking reconfigured the cinematic west into a landscape that's, to use Leone's own words, just as "violent and uncomplicated" as the people who live there. When people heard the word "gunslinger," they used to picture John Wayne. Now, they think of Clint Eastwood.

"The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly" didn't do this alone, of course. Not by a long shot. Sam Peckinpah had something to do with it, as did a number of other great spaghetti westerns, including many from Leone's filmography. But "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly" is the best of the bunch, and its influence transcends genre boundaries. You'll see its imprint in "Star Wars," "Logan," Stephen King's "The Dark Tower," and every film Quentin Tarantino has ever made.

That's the level of craft we're talking about. Eastwood, Wallach, and Van Cleef's trio of treasure-hunting outlaws are the perfect guides to the horrors of the Civil War, and while the film's long and languidly paced, it never drags. And then there's Ennio Morricone's score, which might as well be the film's fourth main character. Close your eyes and listen; even without the visuals, the music tells you everything you need to know.

The Alternate Take: "Unforgiven" is a sequel to "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly" in all but name, and while William Munny isn't technically an older version of the Man with No Name, the whole enterprise gives Eastwood an opportunity to dissect the films of his early career in the same way that Leone tackled the westerns of Hollywood's golden age. (Christopher Gates)

The Graduate (1967)

Mike Nichols' bright, incisive, endlessly stylish film about post-college malaise is the coming-of-age genre at its best and most emotionally complex. When Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) meets seductive family friend Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), the recent California grad who's prone to spending his days floating in the pool finds his life exploding in vivid color. The pair's memorable tryst is the focal point for many a retrospective on the film (how many times have you heard "Mrs. Robinson, you're trying to seduce me, aren't you?"), but "The Graduate" has a whole lot more on its mind than the illicit affair at its center.

When Benjamin ends up separately involved in a relationship with Mrs. Robinson's daughter Elaine (Katharine Ross), the film evolves into a surprising and potent exploration of the trappings of the status quo — the moment in a man's life when "sow your wild oats" turns into "when are you going to get serious?" The film's most famous shot is its last, a stunning oner on the back of a bus that conveys more in silence than the film ever did in words. Still, though, every moment of "The Graduate" feels gorgeously expressive, from those pool shots to a sequence that frames Bancroft as a small, wounded creature in a hallway — not to mention each moment that brims with the energy of the film's Simon & Garfunkel soundtrack.

The Alternate Take: Hal Ashby's 1971 black comedy "Harold and Maude" takes a softer — yet ultimately more melancholy — approach to the May-December romance. In this beautiful and bittersweet classic, death-obsessed teen Harold (Bud Cort) strikes up an unorthodox friendship (and more) with life-loving septuagenarian Maude (Ruth Gordon), and the result is offbeat and indelible. (Valerie Ettenhofer)

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Wes Anderson has only further refined and fine-tuned his so-called dollhouse aesthetic with each new movie, yet it's 2014's "The Grand Budapest Hotel" that continues to reign triumphant in his filmography. The storyteller's magnum opus of pleasing colors and symmetrical compositions is, of course, a feast for the eyes full of candy-colored scenery and the type of droll visual comedy that's rarely found in modern cinema.

There's also a whole lot going on below the decadent surface here. Anderson and his co-writer Hugo Guinness are telling a story that's been passed down by a nostalgic old man and then repackaged by an author within the movie, freeing it up to deal with some heavy subject matter (the spread of fascism in early 20th-century Europe) while retaining a touch as delicate and light as one of Herr Mendl's baked treats. In other words, "The Grand Budapest Hotel" is knowingly romanticizing the past by focusing primarily on its fanciful plot and doing its best to keep the sadder moments in the margins — an act that only serves to make them all the more moving and haunting.

As a whole, "The Grand Budapest Hotel" is much like Monsieur Gustave H. (a never-better Ralph Fiennes): enchantingly ridiculous, comically posh, and more than a little bit naughty, but above all else a truly remarkable one-of-a-kind specimen.

The Alternate Take: Anderson's ode to childhood and young love (in all its ungainly glory), "Moonrise Kingdom" is idiosyncratic, pensive, mischievous, and bittersweet, often at the same time. That is to say, it's a Wes Anderson joint through and through, effortlessly marrying classic film homages with Anderson's quirky original ideas to the point where you can't tell where one ends and the other begins. (Sandy Schaefer)

Groundhog Day (1993)

Every single time loop movie that has been made since "Groundhog Day" has been trying to replicate the greatness of this 1993 wonder. The mere existence of this movie is a bit of a miracle when you consider how it tore apart the friendship of director/writer Harold Ramis and his "Ghostbusters" cohort Bill Murray, but the fact that it's actually a perfect and genuinely funny romantic comedy that manages to fit in tinges of darkness and existential crisis makes it even more special.

Bill Murray has never been better as he slowly loses his mind while living the same Groundhog Day over an over again. Though he may have earned an Oscar nomination for his turn in "Lost in Translation," this is truly the best performance of his career, tapping into everything that makes him a joy to watch. Time loop movies can be especially difficult to crack because they require repeating the same beats over and over again, which means a decent chunk of your movie has to be downright amazing in order for audiences to even tolerate watching scenes over and over again. Witnessing Murray slowly descend into madness, hit rock bottom by killing himself in a variety of creative ways, and then rising up out of the ashes to find meaning in his life never gets tired. "Groundhog Day" finds comedy in the mundane with a little bit of mayhem sprinkled throughout, and it's not just one of the best comedies of all time, it's one of the best films ever made.

The Alternate Take: "Edge of Tomorrow" (or "Live. Die. Repeat.") is perhaps the only time loop movie that has come close to being as good as "Groundhog Day," and it's all thanks to the meshing of some surprising comedy chops from Tom Cruise and the absolute badass Emily Blunt alongside him in some stunning sci-fi action sequences. (Ethan Anderton)

Halloween (1978)

John Carpenter invented the slasher film as we know it with "Halloween," a so-simple-it's-brilliant story of unspeakable, unstoppable evil. It's Halloween and murderer Michael Myers has escaped from an insane asylum to head back home to Haddonfield, Illinois. There, pursued by his psychiatrist, Dr. Samuel Loomis (Donald Pleasence, creating an iconic character by wearing a trench coat and uttering uber-dramatic lines about evil), he begins targeting a group of babysitters who have the misfortune of crossing his path. One of the babysitters, virginal Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), is soon the last girl standing.

Over the years, "Halloween" sequels would expand on the mythology, adding weird new footnotes and caveats. And while those films are entertaining, none of them can match the raw, primal power of the original. What could've easily been a forgotten B-movie became a phenomenon; a film audiences couldn't get enough of, even as they screamed in terror. As the great Roger Ebert wrote in his four-star review of the film, "We see movies for a lot of reasons. Sometimes we want to be amused. Sometimes we want to escape. Sometimes we want to laugh, or cry, or see sunsets. And sometimes we want to be scared."

The Alternate Take: While "Halloween" is perhaps one of the most famous holiday-themed horror titles, it wasn't the first. A few years before Carpenter took us to Haddonfield, Bob Clark gave folks the chills with his creepy slow-burn "Black Christmas," focusing on a group of sorority sisters targeted by a killer. Stylish and scary, it's actually one of two big Christmas movies Clark made. The other? "A Christmas Story." (Chris Evangelista)

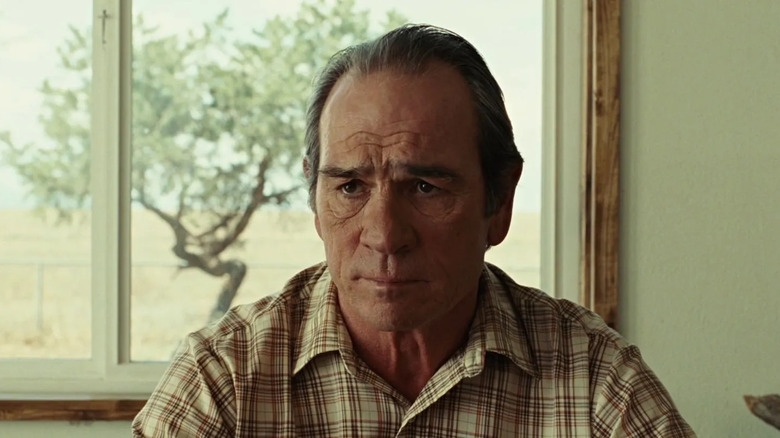

Heat (1995)

"Heat" was advertised as the first time legendary actors Al Pacino and Robert De Niro would share the screen (they previously both appeared in "The Godfather Part II," but never occupied the same scene), but the big Pacino/De Niro meet-up is just one scene in a vast, sprawling crime epic. Career criminal De Niro and his crew are planning one big score when they catch the eye of cop Pacino, and director Michael Mann weaves in and out of the lives of these characters and those around them to weave a brilliant tapestry. It's one of the best crime movies ever made because it's about so much more than crime. It's about the lives these characters live and the traps they build for themselves along the way. At any moment, one of these men can walk away and save themselves and the lives of others around them. But they can't. They're both obsessed with their work because their work is all they know, and if that creates collateral damage along the way, so be it.

All of this culminates in one of the greatest shoot-outs ever captured on screen — a loud, brutal blast of bullets on the streets of Los Angeles as De Niro and his crew do battle with Pacino and his guys. Pacino and De Niro's characters respect each other, but they also won't hesitate to put each other down if need be. Such are the lives of violent, driven men. Mann is obsessed with the locations these characters inhabit, from the parking lots, to the restaurants, to the airports, to the balconies overlooking landscapes of twinkling city lights. "The view right here of the underpass is one of the most beautiful underpasses in the world of beautiful freeway underpasses," Mann says at one point during the director's commentary on the Blu-ray. That's poetry, baby.

The Alternate Take: What's better than this, guys being dudes? Michael Mann's "Miami Vice" was not a box office smash or a critical darling, and yet it's one of his best films, a no-nonsense story of two cops (Jamie Foxx and Colin Farrell) willing to push things to the limit and beyond in order to get their work done. Nestled in the middle of this, like so many other Mann movies, is a doomed love story that will make a mark even if it doesn't survive. (Chris Evangelista)

Inception (2010)

Christopher Nolan built an entire career on stories about men avoiding their emotions, and it's fitting that his greatest work takes that concept and literalizes it within an inch of its life. "Inception" tells the story of Cobb, a thief played by Leonardo DiCaprio, who steals not from your wallet but from your very subconscious, using technology that allows him and his expert associates to venture inside your dreams. Cobb has been tasked with a nearly impossible mission — to give someone an idea instead of taking it — but his personal baggage is so overwhelming that it follows him into other people's heads, and threatens to destroy him, everyone around him, and everything he's built.

"Inception" takes what could have been merely an exciting sci-fi thrill ride and packs it full of overwhelming portent, a tidal wave of uncontrollable psychic damage that threatens to wash away an already exhilarating heist picture. Nolan borrows heavily from Satoshi Kon's anime masterpiece "Paprika," there's no question, but "Inception" feels like a personal expression anyway. It's a disarmingly populist rendition of the filmmaker's own notorious perfectionism, undone or perhaps only made artistically valid by the subconscious chaos he can't prevent from creeping into the periphery. Blockbuster filmmaking rarely gets more inventive, more thrilling, or more personal.

The Alternate Take: Nolan's cold and calculating attempts to control the subconscious make "Inception" a perfect double feature with David Lynch's "Mulholland Dr.," another film about a traumatic relationship and human frailty endangering a perfectly good fantasy. Lynch's film about a naive ingenue who falls in love with a mysterious amnesiac in a phantasmagorical Los Angeles never pretends to be fully logical, and perhaps that's why it feels so perfect; our dreams are a mess, because so are we. (William Bibbiani)

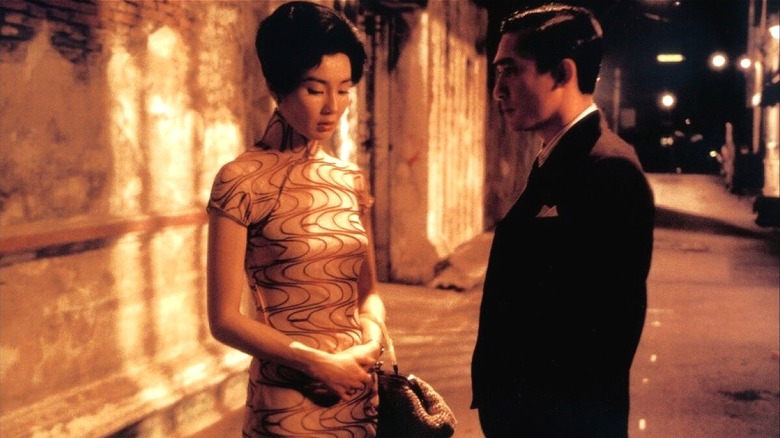

In The Mood For Love (2000)

Never has a love story set in Hong Kong been so beautiful and devastating as Wong Kar-Wai's "In The Mood For Love," which paints a bittersweet picture of loneliness in the midst of a bustling city. While unrequited love evokes pain, reciprocated, yet unfulfilled love alters the very soul of the ones involved, as they exchange longing glances near rain-drenched street corners or share a hotel room and pine for the other in restrained silence.

Adultery sets the plot of "In The Mood For Love" forward, but the focus is on the victims of such an act — Chow (Tony Leung) and Su (Maggie Cheug) share a love that can never be freely uttered or consummated, but only whispered in subtle gestures of affection, the air between them charged with intense sensuality. Wong uses bold, vibrant shades of red to convey these unspoken emotions while weaving character portraits that are deeply flawed, humane, and unforgettable.

The precious moments spent with the one you desire, but cannot have, feels transient and timeless at the same time, and "In The Mood For Love" captures this unique sentiment in heartbreaking ways, etching a tale about a love that endures, a dramatically distinct stance from "Chungking Express" or "Fallen Angels." Moreover, Wong's highly stylized, charged visuals are always a treat to witness, and there is something special about how he frames the simple act of eating streetside noodles alone after work, capturing a range of un-uttered emotions in a single frame.

The Alternate Take: Wong's "2046" anchors love across space and time, where lovers haplessly look for companionship in the wrong places. The sleek, futuristic aesthetic of "2046" is truly one of a kind, as Wong leans into a masterful, experimental examination of the very fabric of human longing and suffering. (Debopriyaa Dutta)

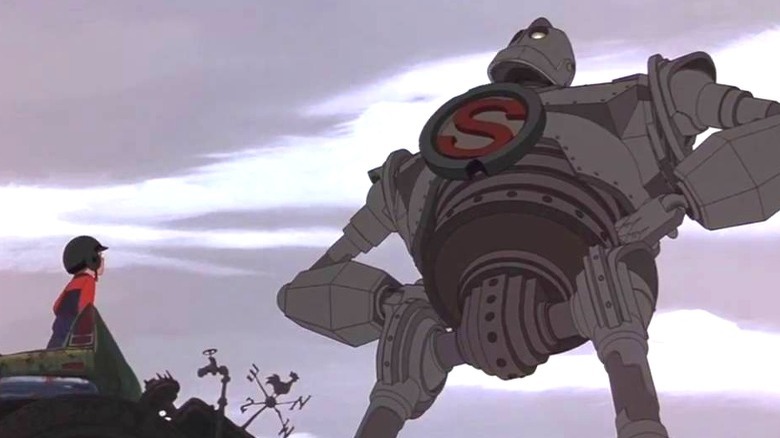

The Iron Giant (1999)

"The Iron Giant" is the best Superman movie ever made, period. A being with unlimited power crash lands on Earth, learns empathy and kindness from its residents, and decides to use his abilities to save humanity, not destroy it? That's the Superman myth in a nutshell. The Iron Giant's choice of Kal-El as his role model shows why Siegel and Shuster's creation has endured for over eight decades, and if that were all "The Iron Giant" had to offer, it would be enough.

But, of course, there's more. So much more. "The Iron Giant" remains one of the best fusions of hand-drawn art and CGI; while the human characters and the backdrops were animated traditionally, the Giant is a digital creation, and his precise, mechanical movements go a long way towards selling his otherness. The story of a living gun who rejects violence felt remarkably potent in summer 1999, when America was still reeling from the Columbine massacre, and hits even harder in today's firearms-plagued world.

And then there's Hogarth Hughes, one of the rare children in an animated feature who acts like a real kid. While the Giant gets all the attention, Hogarth is the one who provides all the heart. He's an over-active, imaginative, and unwaveringly optimistic little guy searching for the Hobbes to his Calvin, and the bond that results once he finds it is unforgettable. "The Iron Giant" is still the only film that makes me cry every single time I watch it.

The Alternate Take: "Superman: The Movie" doesn't have the pathos or tragic sacrifice of "The Iron Giant," but, in addition to providing the framework for the past 15 years of Hollywood blockbusters, it shares the perspective that everyone — human or otherwise — has the innate capacity for good. These days, that couldn't be more refreshing. (Christopher Gates)

It's A Wonderful Life (1946)

Few American traditions are as pure in spirit as the annual "It's A Wonderful Life" rewatch. Nearly 80 years after its release, it still feels like a miracle that Frank Capra's life-affirming portrait of a man on the brink of suicide has become a holiday season staple. That a two-plus-hour black-and-white emotional epic can become among the most popularly revisited classics is music to movie-lovers ears; that "It's A Wonderful Life" is actually a film deserving of this endless love is even more incredible.

James Stewart gives an earnest, effective performance as George Bailey, the man whose life takes a Charles Dickens-inspired turn when he's pushed to the brink by his circumstances. Here, though, the guardian angel who guides him through the past and present is less moralizing and more realistic, as "It's A Wonderful Life" reckons with surprisingly modern-feeling problems involving money, family, and reputation. Even among the best movies ever made, very few feel like they possess the power to change a life, but "It's A Wonderful Life" has a sort of transformative spirit that can bring a tear to the eye of even the most cynical among us. With each rewatch, George's fresh start feels like it can be ours, too, and we're left, above all else, with a weightless feeling of possibility. "It's A Wonderful Life" is movie magic at its finest.

The Alternate Take: Another Capra classic, "It Happened One Night," is a pre-code gem about love and money that features scintillating turns by Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert. A formative rom-com before the term existed, it's clever, bold, and surprisingly sexy. (Valerie Ettenhofer)

Jaws (1975)

The movie that gave birth to the summer blockbuster! What, exactly, can one even say about "Jaws" at this point that hasn't been said a thousand times over? It's the tale of a page-turner morphing into a movie shot by a still relatively green filmmaker (you know who he is), running over budget and overschedule, complete with a robot shark that kept malfunctioning. And yet from that mess rose one of the biggest movies of all time — and one of the best.

Steven Spielberg's "Jaws" is a lean-mean machine of a movie; a man-vs-nature tale where nature just happens to have huge freakin' teeth. Roy Scheider is Martin Brody, the police chief of Amity Island, and he's one of the first people to sound the alarm when a great white shark starts munching on swimmers. But capitalism reigns supreme, and the mayor and other greedy townsfolk want to keep the beaches open for the summer. Big mistake, guys.

When things get too deadly, Brody, marine biologist Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss), and local salt Quint (Robert Shaw, who chomps more scenery than the shark) head to sea to stop the beast once and for all. Spielberg stages big, show-stopping set pieces, but he also focuses on little moments — like one of Brody's kids mimicking his father's actions at the dinner table, or the three men bonding over their various scars while they wait to kill the damn shark. It all works, and works perfectly, aided by John Williams' brilliant score full of primal notes that immediately trigger dread every time we start to hear them.

The Alternate Take: If "Jaws" was Spielberg's ascension into blockbuster filmmaker stardom, "Schindler's List" is the film where he finally proved once and for all that he wasn't just a popcorn entertainment guy — he was an artist. Spielberg had been trying his hand at "serious" movies before "Schindler's List," but none of them quite clicked. Then he got his hands on the true story of Oskar Schindler, who used his munitions factory during the war as a cover to save the lives of 1000 Jews. Spielberg uses every populist filmmaker trick he had learned up until that point to tell a harrowing, crushing, ultimately hopeful story that never flinches away from the horrors of the Holocaust. And the end result finally won the filmmaker the Best Director Oscar he so craved. (Chris Evangelista)

Jurassic Park (1993)

Steven Spielberg may well go down as the best to ever do it when all is said and done. That's why you see his name on this list more than once. And when Spielberg is firing on all cylinders, true movie magic happens. Such was the case in 1993 when he made "Jurassic Park," one of the most beloved and enduring blockbusters in the history of blockbusters. We may take it for granted now, but the film makes dinosaurs feel real for the first time ever. To this day, the T-rex breakout sequence is a shockingly convincing bit of filmmaking that allows even the most skeptical of viewer to suspend disbelief for the sake of sheer wonderment.

Perhaps more than the arguably perfect movie experience that the film itself represents, Spielberg also carved a path forward for the next three decades of filmmaking, introducing groundbreaking CGI that allowed for these creations to come alive, while also using equally groundbreaking animatronics to complete the picture. The marriage of the two in this adaptation of Michael Crichton's novel of the same name remains a touchstone for anyone trying to do the same. When we talk about groundbreaking films, this is right near the top of the list. More importantly, when we talk about great blockbuster entertainment that also functions as a pure expression of the art form, "Jurassic Park" is also right near the top of that list. Put simply? It's the definition of greatness.

The Alternate Take: Before Spielberg was making gigantic box office hits, he made what has been called the greatest made for TV movie in history in 1971 with "Duel." With limited resources and a tiny budget, what the director was able to accomplish is nothing shy of a minor miracle and demonstrates that, even then, he was a master of his craft, particularly in making a true edge-of-your-seat thrill ride. (Ryan Scott)

Kiki's Delivery Service (1989)

For its first half, Hayao Miyazaki's "Kiki's Delivery Service" is exactly what you'd expect from the legendary Japanese animation company Studio Ghibli. Its stunning blend of fantasy and naturalism — brought to life with hand-drawn animation so perfect and composed that you could happily frame every moment — immediately draws you into the world of Kiki, a young witch who sets off on her own and starts a delivery service, racing around her new community on broomstick. It's charming. It's funny. It's a world you want to live in and luxuriate in, populated by a sprawling cast of characters who win your heart within moments.

But it's the back half of the film that takes a sledgehammer to your heart, as Kiki learns that turning what you love into a career can have dire emotional consequences. Her magic falters and her ability to fly vanishes — everything she once loved now feels hopeless, joyless. It's a turn that's brutal but earned, the best-ever depiction of burnout, embedded into a tale of young witches and talking cats. Miyazaki's ultimately a big softie (he gives us the happy ending we want), but this is the greatest example of what the master animator and his team of geniuses at Studio Ghibli could pull off: A brilliantly realized fantasy universe given all the relatable emotional stakes of our own world.

The Alternate Take: You can't go wrong with literally any other Miyazaki movie, but "Spirited Away" is considered by many to be his masterpiece, and for good reason. But really, you can pick any of them. (Jacob Hall)

King Kong (1933)

Only a few years after sound became a mainstay in motion pictures, directors Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack assembled one of the greatest and most influential adventure movies ever made. An incalculable number of creature features came out in its wake, but the original "King Kong" still holds up where many of its imitators do not. A primary reason for its staying power is because Kong's emotions don't ever get lost in the wildly impressive technical wizardry of Willis O'Brien's stop-motion effects. He's more than just a lumbering brute or a gimmicky visual trick — he's an actual character with thoughts and feelings that you can track through facial expressions and body language, adding a layer of sophistication that separates this from its contemporaries. There's no getting around the rampant racism and misogyny on display here, which are indicative of the era in which it was released, but Fay Wray's movie star performance transcends the scream queen sobriquet and gives her the opportunity to convey real, human, relatable reactions to the chaos unfolding around her. More than 40 years before Steven Spielberg would essentially create the blockbuster with "Jaws," "King Kong" was the summer blockbuster to end all summer blockbusters.

The Alternate Take: For the most famous international riff on a giant monster movie, seek out the original 1954 version of "Godzilla," the best film ever made about the existential horror of nuclear war. (Ben Pearson)

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

There are "big" movies, and then there's "Lawrence of Arabia," arguably the very personification of epic filmmaking. This is not only the longest movie to win Best Picture at the Oscars, but it remains one of the purest examples of what you can only do with the format of cinema, of telling a story that only works when using the biggest possible screen.

David Lean takes the legendary tale of T.E. Lawrence and his role in the Arab Revolt and interrogates the myth that had been built around the man and the idea of white saviors and messiahs, of the British Empire and its history of colonialism. Even 60 years later, most of the many, many movies influenced by "Lawrence of Arabia" miss this part. And Peter O'Toole is integral to this. Impossibly handsome and enigmatic, O'Toole gives nuance to the character that grounds the grandiose elements of the story. He does not play to the legend, but keeps enough cards close to the chest that the audience doesn't never fully gets to know him. It's a legendary figure imbued with mystery and humanity.