A24's Men Ending Explained: They're Just Normal Men - Or Are They?

Since she first gained national attention in the UK on the BBC talent show "I'd Do Anything," Jessie Buckley has made a memorable impression playing women who find themselves in the company of dangerous men. On the show, she competed the role of Nancy, the tragic wife of abusive Bill Sykes in a new stage version of "Oliver!" Nine years later, she made her film debut in "Beast" as Moll, a young woman who falls for a charismatic drifter who may or may not be a murderer. In the same year, she aided Tom Hardy's brutish protagonist wage his personal war against the powerful East India Company in "Taboo."

More recently, in the Oscar-nominated "Women Talking," she joined an excellent ensemble playing a group of women who are systematically drugged and sexually assaulted by the men in their community. Is it that she's drawn to roles where she can tackle toxic masculinity? Or is it just that men in real life often behave toxically towards women, and that is reflected in the roles on offer?

Either way, Buckley has become one of the most compelling actors around and Alex Garland's "Men" gave her the chance to face off against a whole village full of malevolent blokes, all of whom look uncannily similar. In the #MeToo era, there is simply no avoiding the klaxon-blast of the title and that its central premise is a literalization of the old saying that "men are all the same." Also contained within the film is a thoughtful exploration of grief and trauma, which gets a little lost in the noise of Garland jumping up and down on his hot-button topic and the much-talked-about body horror finale. The result is a film that feels simultaneously on-the-nose and obtuse, stuffed with symbolism and ideas. There is a lot to unpack, so let's get into it.

So what happens in Men again?

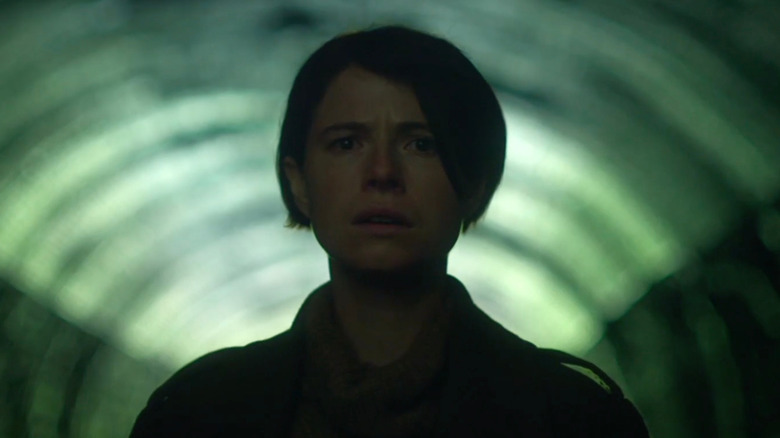

Grieving the death of her husband James (Paapa Essiedu), Harper Marlowe (Jessie Buckley) decides to get away from London and take some time for herself. She splurges on renting a gorgeous country house in the small village of Cotson, where she is welcomed by genial homeowner Geoffrey (Rory Kinnear).

Harper is traumatized by her last few moments with James before he died. In flashback, we see how he emotionally blackmailed her by threatening to take his own life if she divorced him, before growing violent and hitting her. We later learn that he fell to his death while trying to climb down to their balcony from the apartment above after she kicked him out. It isn't clear whether he slipped or made good on his threat and Harper is haunted by the image of him plunging past their window.

Things get creepy when Harper starts exploring her surroundings. She goes for a stroll in the woods and comes across a disused railway tunnel. Calling out and enjoying the echo of her voice, she is frightened when a man appears and the other end and sprints towards her. She runs away, only to spot a naked man standing brazenly outside a derelict cottage. The latter follows her back to the house and tries to break in. The police arrive and apprehend the vagrant, and that's when it becomes clear that all the males in this village have the same face (and all are played by Rory Kinnear).

After an unsettling encounter with an abusive schoolboy called Samuel and an inappropriate vicar, she checks out the village pub and is furious to learn that the police released the naked man, failing to take her concerns seriously. She decides enough is enough and wants to leave, but the men of Cotson aren't done with her yet.

Men's sensational body horror ending

Around the hour mark, "Men" switches from slow-burning folk horror to a hallucinatory home invasion thriller, culminating in a gloopy showstopper that is likely to go down as a classic body horror moment. Angered by her encounters with the men of Cotson, Harper calls her best friend Riley (Gayle Rankin) who decides to drive down to the village to join her. However, it is a four-hour drive, which is a long time to wait when the men suddenly besiege the house, attempting to break in and attack her.

Harper tries to flee the village, only to be assaulted and chased back to the house by Geoffrey. He suddenly transforms into the Naked Man, who has transformed into the mythological Green Man. As he approaches her, his belly bulges and he falls to the ground. She watches in horror as a figure emerges from a vagina that has appeared where his anus should be. It is a newborn but fully formed Samuel, who screams like a baby as his own stomach begins to distend.

The cycle continues: Samuel gives birth to the Vicar, who in turn gives birth to Geoffrey. By this stage, Harper has seen enough. She walks away into the house, followed by the pathetic creature. Finally, Geoffrey gives birth to James, who is back to guilt-trip her again from beyond the grave. Harper can only look on with pity, picking up an ax to defend herself. She asks what he wants from her and he simply says, "Your love." She ambiguously replies, "Yeah," testing the sharpness of the ax blade with her finger.

In the morning, Riley pulls up at the house. She discovers evidence of the previous night's mayhem and fears the worst, but then spots Harper sitting calmly in the garden. Harper sees her friend and smiles.

The men in Men

To fully appreciate the ending of "Men" it is worth digging into the many themes that feed into the shocking conclusion. The most obvious is Alex Garland's approach to toxic masculinity, which hinges on the film's central "Twilight Zone" style gimmick: All the men in the village are literally the same! The multiple parts are brilliantly played by Rory Kinnear, who finds many clever non-verbal ways to differentiate each character. It's a virtuoso performance, but at times I couldn't shake the feeling that I was watching a feature-length sketch from "The League of Gentlemen," the black comedy folk horror series with Reece Shearsmith, Steve Pemberton, and Mark Gatiss all playing various characters in the sinister village of Royston Vasey.

Every man in the film behaves badly towards Harper, from careless micro-aggressions to full-on murderous misogyny. The most unforgivable is James, a man who supposedly loves her but tries to exert control with physical and emotional abuse. While he is clearly a physical threat to her, we also see how his attempts to overpower her come from a place of neediness and psychological weakness, which is a theme that re-emerges in the film's surreal conclusion.

Once in the village, we see a range of behavior from the male folk. Her landlord Geoffrey is initially the most benign of the bunch, but he oversteps boundaries with his clumsy small talk, old-fashioned notions of gentlemanliness, and bumbling gallantry. Next, she meets the Naked Man, who is a more ambiguous figure than he first seems. At first, he comes across as a flasher, flagrantly imposing his nakedness on her. Later, we see that he's probably naked all the time and not just when he's revealing himself to women, as he transitions into the physical embodiment of the Green Man.

How the men in Men reflect aspects of British society

The range of ages and occupations of the male characters in "Men" illustrate how toxic masculinity permeates all aspects of British society, from supposedly innocent schoolchildren to law enforcement and the clergy. The Police Officer, who is respectful enough towards Harper but casually dismisses her fears, can be seen to represent the depressing statistic that under 1% of reported sexual assaults in the UK lead to a conviction.

The troubled schoolboy, Samuel, shows that misogyny can be inherent from an early age. He petulantly calls her a "stupid b****" when she refuses to play with him and, during the finale, we see him messing with a dead crow that crashed into the house earlier. He has put a plastic mask of a blonde woman over its head and moves it rhythmically on the kitchen counter, suggesting intercourse. In Britain, "bird" is a sexist slang term for a woman, and a recent survey revealed that one in five teenagers watches porn regularly, correlating with a rise in sexual assaults in schools. It isn't a stretch of the imagination to think that Samuel is mimicking the motion he has seen in pornography.

The worst figure in the village is the Vicar, a lustful hypocrite who represents society's willingness to turn a blind eye to abuse against women. He initially seems sage and compassionate as he comforts Harper outside the church, but oversteps the boundaries by putting his hand on her knee. To add insult to injury, he suggests that she was to blame for James's death and that men hitting women is just a fact of life. Notably, when she walks away from him, he rests his hand where she was sitting and lets his finger fall between the slats, a suggestive gesture that foreshadows what is to come.

Symbolism in Men

"Men" is loaded with symbolism. Alex Garland intermingles Christian and pagan imagery, which should come as no surprise given its setting in the English countryside, where ancient monuments still have a powerful hold on the landscape and the imagination. The most obvious Christian reference comes when Harper arrives at the house and helps herself to an apple from the tree in the garden. In case we missed the nod, Geoffrey jokingly scolds her for taking the forbidden fruit. Further invoking the tale of Original Sin, Naked Man also takes an apple when he follows her home, his nude form alluding to Adam.

As Harper explores the village church, she discovers two mythological figures carved on the font. On one side, there is a classic image of the Green Man commonly found on the masonry of medieval churches, not to mention pub signs across the country. On the other side is Sheelagh na gig, unapologetically spreading her oversized vulva. Despite the lewd gesture, she is also found in churches, with hundreds of examples in Ireland.

They are both symbols of fertility and rebirth, although the true nature of Sheelagh na gig is still a little hazier. Was she meant to scare away evil or serve as the embodiment of sin? The Green Man, along with the phallic maypole, is a masculine symbol of fertility while Sheelagh na gig is fearlessly female. In more recent years, feminists have reclaimed her as a symbol of empowerment.

The decision to include both is important to the film's central thesis. Later, we see that the Naked Man has morphed into the Green Man to continue his pursuit of Harper. This casts her as Sheelagh na Gig, although it isn't quite clear what he wants from her. As we find out, he doesn't need a female counterpart to continue his cycle of reproduction.

Further allusions in Men

If the Green Man in "Men" harks from medieval English folklore and the Sheelagh na gig is predominantly Irish, there is another element of aggression in play in the form of Anglo-Irish relations. Jessie Buckley reverts to her native Irish accent for the film and Geoffrey thoughtlessly calls the Naked Man a "gypo," the British derogatory term for Irish Travellers, common in mainland Britain but who have no relation to Romani "gypsies."

If Harper is the Sheelagh na gig of the story, then the idea of her private parts is both a source of intense lust and terror for the men in the village, reflecting the duality of the stone effigies of Sheelagh found on churches: Is she attracting evil or warding it away? This is clarified by the vicar's speech during the home invasion:

"You are singing to me, not as Ulysses but a sailor, to dash me to pieces on the rocks of this... these rocks... this cave... this slit... this... what is this? Yes, exactly. It's the tip of the blade."

This scene bursts with allusions and psychology, and the Vicar blaming his lust on Harper is reminiscent of the misogynistic excuse that women invite sexual assault by wearing revealing clothing or giving off certain signals. He is clearly obsessed with Harper sexually, but he is also afraid of her sexuality. His speech brings in elements of Sigmund Freud's theory of castration anxiety and the folk tale of Vagina Dentata (toothed vagina), which threatened genital mutilation or castration of a man attempting intercourse. Lastly, when Harper discovers that the Green Man is pregnant, it seems that he is suffering from a literal case of Vagina Envy. He's about to give birth, but from where?

Alex Garland's take on the final scene

All these themes and symbols come together in the finale of "Men," but to what end? As much as I appreciate a director crediting the viewer with intelligence, I couldn't help the nagging sensation that Alex Garland hedged his bets by making it both allegorical and literal. As he told Indiewire:

"There are different ways of interpreting the film or deciding what it's about, but in terms of what I felt it was about, if it turned out to be all in her head, it would have made the film borderline unethical. There was never any intention to do that."

That is all well and good and I usually feel a bit cheated when the events of a movie turn out to be something that's going on in a character's mind, but the ending of "Men" is also a cop-out by trying to be all things at once. From the moment the male attackers start appearing at random and all showing the same ghastly vaginal wound on their arm (which also corresponds with one of the injuries James suffered in his fatal fall), it scans as a psychological horror like Roman Polanski's "Repulsion," where the character's state of mind is projected onto reality.

For this story to work and pay off allegorically as no doubt intended, some of it has to be in Harper's head. Otherwise, what is the point of having all the men in the village look the same, something that she doesn't seem to pick up on? Without her making the connection, the gimmick is solely there for our benefit and doesn't add to her experience at all. If she doesn't notice, then you might as well have a straightforward survival horror where she comes under attack from various blokes played by different actors.

My take on the ending of Men

So here's my take on it from the standpoint that some of it must be in Harper's head for the film to work. After the trauma of her break-up with James and his death, Harper projects her pain, grief, and wariness of men onto the first guy she meets in the village, Geoffrey. He makes her feel uncomfortable, causing her to unconsciously see all the other men in Cotson as the same.

Despite his bungling demeanor, Geoffrey is the one and true villain of the piece. His comments in the pub suggest that he has been following her as he seems to know exactly where she went during the day, and the man in the tunnel wears a jacket of a similar length to his and runs with the same lumbering gait.

It is Geoffrey who chases her and attacks her in the house, In her distress, she sees him as all the horrors that women suffer at the hands of men personified by the endlessly rebirthing creature. All the symbolism from Christian and pre-Christian times suggest that toxic masculinity, including the gaslighting and victim-blaming she encounters in the village, is an age-old problem that keeps reproducing itself to this day.

Finally, she projects her feelings about James onto Geoffrey and kills him with the ax to end the torment. When Riley arrives she finds Harper transformed. She has survived the ordeal and exorcized her demons by slaying her pursuer, and she is now ready to move on with her life. But, as Alex Garland said, it's up to the viewer to decide what it's all about, making the film more successful as a talking point than a horror movie.