A.I. Filmmaking Is A Terrible Idea, And One Underseen Movie Shows Us Why

As the writers' strike pushes against Hollywood's embracing of A.I., one underseen drama, "The Congress," reminds us why humanity in filmmaking matters.

After months of speculation and failed negotiations, the Writers Guild of America put down their pens and went on strike this month. The entertainment industry has shifted exponentially in the past 15 years since the last WGA strike, thanks to the dominance of streaming services and changes in the residual process. One of the key areas where the guild is fighting for security is the growing presence of artificial intelligence in their field. In a list of their proposals, sent to the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), the WGA sought to regulate the use of A.I. in writers' rooms and wanted assurances from studios that it would not be used to write or rewrite material. They also want to block it from being used as source material. The AMPTP rejected these proposals with a counter-offer of annual meetings to discuss advancements in technology.

The WGA's fears are certainly not unfounded. The tech already has some fans in its corner, most notably "Avengers: Endgame" co-director Joe Russo. In an interview with Collider, Russo, who serves "on the board of a few AI companies," said,

"Potentially, what you could do with [A.I.] is obviously use it to engineer storytelling and change storytelling [...] You could walk into your house and save the A.I. on your streaming platform. 'Hey, I want a movie starring my photoreal avatar and Marilyn Monroe's photoreal avatar. I want it to be a rom-com because I've had a rough day,' and it renders a very competent story with dialogue that mimics your voice."

Russo also theorized that A.I. will be able to "actually create" a movie within "two years." Many people have already noted the vast problems with Russo's vision of the future, one where the creative process is bereft of creative people. Stripping people from art seems antithetical to its entire purpose, as well as a sign of a bleak anti-human future. A curious and underseen sci-fi drama from ten years ago examined this potential future. There's no better time than now to revisit it.

The Congress is a very different animated film

Filmmaker Ari Folman made a major impact on cinema in 2008 with "Waltz with Bashir," a documentary about a soldier's experiences during the 1982 Lebanon war. To capture the surrealistic frenzy of war and a soldier's struggles with PTSD, Folman animated the narrative, using a dreamlike style that evoked old-school rotoscoping techniques. It became the first animated film to receive a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and offered a fascinating new path forward for the medium. For his next film, Folman decided on a speculative tale that would blend live-action and animation, all in the name of dissecting humanity's divorce from reality.

2013's "The Congress" takes light inspiration from the novel "The Futurological Congress" by Stanisław Lem, but the meat of its story is entirely Folman's. Robin Wright plays an aging actress named, uh, Robin Wright, whose diva-esque reputation and series of box office flops have seen her career take a hit. After her son is diagnosed with Usher Syndrome, a condition that will eventually leave him blind and deaf without treatment, she makes a drastic decision. A film studio, Miramount (get it?), offers to buy her likeness, which will allow them to digitize Wright and put her in whatever movies they want. Robin agrees, for a hefty sum, under the condition that she never act in real life again. Her body is scanned, and soon Miramount has made "Robin Wright" a major movie-star. Over the decades, she becomes the face of the tech, which soon sees Miramount become the monopolistic power of an entire A.I. society. Eventually, she questions the seeming utopia she helped to normalize.

How The Congress tackles A.I. in film

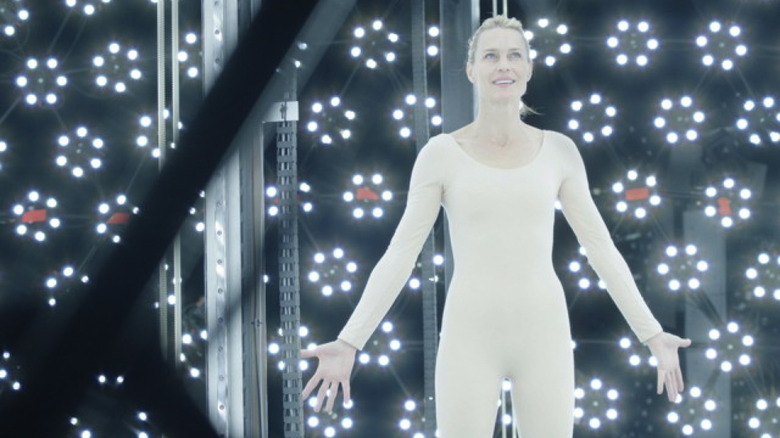

After agreeing to sign away her likeness, Robin is scanned in a machine that captures as much of her persona as possible. She's asked to smile, cry, react, do everything one would expect from an actor. The studio CEO says he wants to keep her young forever, to make her the Robin of her "prime." Soon, "Robin Wright" is the star of a seemingly never-ending schlocky franchise called "Rebel Robot Robin." This action-focused assembly line of movies doesn't seem to require its leading lady to do much acting, using her more as a hot girl who punches robots. Indeed, it's not exactly the kind of movie one would expect Robin Wright to make. But that's the point: remove the actor from the process and you can make them do whatever you want, their own desires or consent utterly inconsequential.

Twenty years pass, and the real Robin (whatever that means in this narrative) is invited to speak at a Miramount conference. The event is held in an animated city, a world where anyone can become a cartoon avatar of themselves, but do to so, they must use addictive hallucinogenic drugs to enter a passive state of mutual distortion. This world is undoubtedly beautiful, the Fleisher brothers-inspired magical mystery tour that the Metaverse wishes it was. It's a place where anyone can pay to be Robin Wright, or do basically whatever they want with her, including putting her in pornographic situations. This evolution in the tech becomes a step too far for Robin, but it's out of her control, and as the decades pass, more people choose to live a drugged-up life in an A.I. utopia than deal with the crumbling recesses of the real world that Miramount has monopolized into oblivion.

A.I. actors are already happening

Wright becoming a computer actress, independent of her instincts and organic talent, seemed like pure fantasy only a decade ago. Now, however, it's so commonplace that we're no longer dazzled by it. Even 13 years before "The Congress," we saw how "Gladiator" recreated the late Oliver Reed to give his character a proper conclusion after the actor died mid-production. Since then, the technology has only grown more sophisticated and more ordinary a filmmaking tool. This VFX has been used to de-age multiple actors in Marvel movies. Carrie Fisher was brought back to life in "Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker" after she passed before production could begin. Bruce Willis sold his likeness so a deepfake version of him could appear in Russian telecom adverts. In 2019, it was announced that James Dean, who has been dead since 1955, would be digitally resurrected for a role in a new film (although there hasn't been any news on that project since.)

This is the future that actors must prepare for, one where they must negotiate for rights to their own body in projects that could happen long after they've died. The late Robin Williams ensured that, after his death in 2015, nobody could use his likeness or image for 25 years after his passing. Earlier this year, SAG-AFTRA announced that "the terms and conditions involving rights to digitally simulate a performer to create new performances must be bargained with the union," suggesting the issue is now so frequently raised in negotiations that a solution is required. If studios are so eager to have A.I. take over the writing aspect of filmmaking, what's to stop them from hoping to do the same with the actors?

The Congress understood the problems of A.I.

Stanisław Lem's novel was an allegory for living under a communist dictatorship, but through Folman's gaze, he utilized its themes to explore the growing and near-unstoppable force of the entertainment industry. At a time when media monopolies are larger than ever and workers' rights are being smudged away, the looming shadow of A.I. hangs overhead. The advancement of A.I. is a mere symptom of a much larger and more pervasive problem, which "The Congress" understands. The continued supremacy of artificial intelligence in all its forms presents such possibilities but in corporate practice, it usually leads to job losses, stripping of identity, and total fragmenting of community and society. The dehumanization of everything for the purpose of profit is not one where art or humanity can truly survive.

"The Congress" deeply believes in the power and necessity of art, particularly cinema, to revolutionize change. But great art can't be calculated by data or downloaded from a series of pre-planned movements. The A.I. Robin clearly isn't the same as the true Robin, an actress of deft talents who can do far more with her spontaneity as an actress than a program. In the world of "The Congress," the desperation to push A.I. forward as much as possible exacerbates the decline of our own world. Hollywood might not be heading into waters so dystopian just yet, but the eagerness to prioritize A.I. as a money-making tool is dependent on the continued dilution of artistic and human-driven worth. That's why the writers are striking. Their work has value that no computer could capture. No A.I. would have the self-awareness to create "The Congress," not when it's a film that cares far more about people than profit.