Beau Is Afraid Subverts Ari Aster's Most Controversial Motif

This piece contains spoilers for "Beau is Afraid."

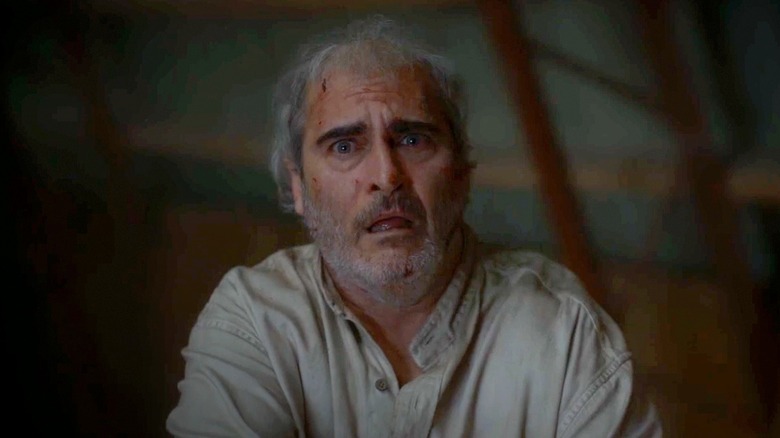

There is a lot to take in with "Beau is Afraid," perhaps the strangest studio movie to get a nationwide theatrical release in a bit. Sure, that sounds a little hyperbolic, but given the current theatrical outlook full of superhero schlock and sequels, it almost feels like a miracle that we're getting Ari Aster's weird three-hour dramedy on the biggest screens possible. It also seems really fitting that "Beau is Afraid" has become his most widely-marketed film, as it seemingly completes his transition from a promising indie director to one of the few true auteurs of his age.

This transition has been filled with its ups and its downs, something that "Beau is AFraid" seemingly acknowledges within its grand story. Perhaps the most significant mark against Aster's creative career was a particular motif from his first two films, "Hereditary" and "Midsommar," that critics said exploited facial disabilities for shock value. It's not hard to understand where they were coming from — both characters this motif was used for were exploited, with one "enhanced" with facial prosthetics, and both killed gruesomely as their stories' sacrificial lambs. While the general idea of these characters being pure souls forcibly corrupted and then killed for their purity is an interesting one, perhaps going the ableism route wasn't the best idea.

Thankfully, "Beau is Afraid" continues that intriguing motif in a new, arguably more impactful way.

Tragedy befalls you

What makes Aster's new take on this recurring symbol so interesting is that he has completely forgone the disability route in depicting it. Rather, the tragic sacrifice of the film is bestowed upon an unnamed man adorned with tattoos (Karl Roy), one of many that enter the crummy apartment building of the titular antihero (Joaquin Phoenix) for seemingly no reason. It's heavily implied that the drug manufacturing conglomerate that Beau's mother Mona (Patti LuPone and Zoe Lister-Jones) has caused the entire country to lose their minds, and this distinguishable man is no exception.

After having to sleep on the scaffolding outside his apartment complex, Beau returns to his ransacked apartment to find the tattooed man dead, apparently bitten by a brown recluse that's been terrorizing the building. What makes this reveal even worse is that he had gotten ahold of the hapless protagonist's phone and tried to call 911 on it, dying before he could type out that last "1" on the phone keypad.

Not only does this emphasize the character's humanity in a world where most people have had theirs taken from them, but it also shows just how depraved the film's society truly is. You can be killed by something so preventable, yet in a world gone mad, nobody will even try to collect your body. How this eventually ends up mirroring Beau's relationship with his mother, specifically how they accuse each other of forcing them to die alone, is surprisingly poignant even two hours later.

Peace refused

Although the tattooed man isn't as much of a character as his predecessors, his presence is still extremely impactful for the rest of "Beau is Afraid." In a weird way, he isn't unlike Beau himself — an aimless figure cast aside by the society that created him. However, what separates the tattooed man from Beau is his self-awareness. He was aware of his condition enough to try and get real help, even if the law enforcement in this universe consists of a bunch of gun-happy fascists. Beau, on the other hand, refuses to be self-aware, blaming Mona for his insecurities and fears rather than accepting that maybe he could've grown from them. His refusal to do so was a conscious choice, unlike the man's recognition of his brown recluse bite.

What was also a conscious choice was the framing of this man as the symbol of the central idea Aster has seemingly built his entire career on, without relying on ableist tropes. It's proof that he understands and accepts the criticism that has been thrown his way, something surprising for a filmmaker of his caliber. Auteurs are often stereotyped as being rejective of criticism, but there's no doubt that "Beau is Afraid" has garnered strong negative opinions since its release. The fact that Aster seemingly isn't too stubborn to evolve, at least to some degree, yet is still able to convey the themes that drive his work regardless, is surprisingly mature and admirable.

After all, what's the fun of being an artist if you can't allow yourself to grow?