The 1969 Oscars Were Old Hollywood's Last Gasp Of Life, And It Probably Came Too Late

(Welcome to Did They Get It Right?, a series where we take a look at an Oscars category from yesteryear and examine whether the Academy's winner stands the test of time.)

If you're ranking the most important years of American cinema, it's pretty difficult not to slot 1967 at number one. That year brought forth a major cultural and artistic shift in the medium, forever changing what American audiences thought cinema could be. This was the arrival of the New Hollywood and featured films that did more than just push the boundaries of mature subject matter, violence, and politics on screen. They destroyed them. The two pillars of the year were Arthur Penn's bloody, sexy "Bonnie and Clyde" and Mike Nichols' coming-of-age dramedy "The Graduate," each becoming two of the three highest-grossing films of the year.

When the 1968 Oscars ceremony rolled around, both films found themselves in the best picture category. However, the filmmaking landscape they were destroying was still popping its head in with the reviled mega-musical "Doctor Dolittle" and the gentle race comedy "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner." Ultimately, "In the Heat of the Night" won the top honor, which was a fine middle ground between the two camps.

New Hollywood was here, but the establishment wasn't going down without a fight. They wanted to make it known their old-school models were as successful as ever. While that wasn't really true culturally, the Academy itself was going to double down on this mentality. Just look at the best picture nominees from the following year: "Funny Girl," "The Lion in Winter," "Rachel, Rachel," "Romeo and Juliet," and the winner, "Oliver!" They pulled away from the New Hollywood ethos so far that they awarded what is still to this day the only G-rated film to win best picture.

The allure of the giant-scale musical

If you wanted to win best picture in the 1960s, you adapted a big hit Broadway musical. "West Side Story," "My Fair Lady," and "The Sound of Music" all took home the top award. These were mega-budget spectaculars and the last guaranteed moneymakers in Hollywood. The only one that wasn't also the highest-grossing film of its year was "My Fair Lady," which came in second place to "Mary Poppins," another musical. Television was on the rise in a major way, and Hollywood's way of combatting that was boosting the scale and the spectacle, giving audiences something they could never get at home.

The previous year, "Doctor Doolittle" was the first indication that this trend could only last so long, but plenty of other films were still in production of a similar ilk. Luckily for the studios, two of them hit in 1968: the highest-grossing film of the year "Funny Girl" and the fifth-highest "Oliver!" Both films were helmed by celebrated masters in William Wyler and Carol Reed, respectively, and convinced Hollywood that the new fad in filmmaking from the previous year could've just been some kind of aberration; a momentary blip of radicalism before everything settles back to what Hollywood dictates the trends to be.

As for why "Oliver!" overtook "Funny Girl" for the win despite it not being quite as starry or financially successful, I think it just comes down to something simple: it's a better movie. "Funny Girl" is a star-making vehicle for Barbra Streisand — who won the Oscar for best actress (in the only tie in an acting race in history) — but it's not the most satisfying dramatic piece. Meanwhile, "Oliver!" is pretty lovely. Not particularly ambitious, but a lovely rendering of a lovely show. That was enough.

The prestige of stage-to-screen adaptations

Beyond the fact that there were two Broadway musical adaptations nominated for best picture this year, there were a total of four nominees based on works from the stage, as "The Lion in Winter" and "Romeo and Juliet" were also plays — be it non-musical ones. There is a long-held belief in the prestige of the theatre. Cinema is for the masses, but the theatre is for those who care about art. Of course, this is a silly frame of mind, but in positioning films for awards races, being able to point to it being a successful adaptation from a celebrated stage work lends it a lot of credibility in the Academy's eyes.

Don't let this make you think I am not a fan of these movies. I have already written about how I believe Peter O'Toole should have won his Oscar for "The Lion in Winter," and despite its highly controversial use of nudity, Franco Zeffirelli's "Romeo and Juliet" is my favorite William Shakespeare film adaptation of all time. My point here is that these films snuggly fit inside Hollywood's box for what an Oscars film should be at a time when the culture was in turmoil. Cinema was changing and being embraced for it, yet the Academy used 80% of its best picture slate to recognize costume dramas adapted from the stage. That goes beyond not having your finger on the pulse. That's ignoring the pulse altogether.

A small glimmer of change

The final film nominated for best picture at the 41st Academy Awards is not something I would exactly categorize as a New Hollywood movie, but it certainly contains far more in common with that movement than the other four nominees in the category. That fifth slot went to "Rachel, Rachel," the directorial debut from Paul Newman and starring Joanne Woodward. Like "In the Heat of the Night" the year before, "Rachel, Rachel" acts as a sort of bridge between the two Hollywood camps that both sides could ultimately agree upon.

On the side of old Hollywood, Paul Newman is a long-established and beloved movie star. Prior to "Rachel, Rachel," Newman had been nominated for four Oscars for best actor with his most recent coming just the year before for "Cool Hand Luke" — yet he won none (and wouldn't until "The Color of Money"). The film was also based on the recent award-winning novel "A Jest of God," and next to theatrical adaptations, the Academy also loves a literary adaptation. On the side of New Hollywood, though, this is a contemporary story — the only one in the bunch — and deals with the sexuality of the day, notably female sexuality.

"Rachel, Rachel" is very much a classical American melodrama that Newman updates for the modern day. It successfully accomplishes being a good transitional film between the two phases of Hollywood, but for something to represent a transition, both sides need to be accounted for. The Academy presented a slate where "Rachel, Rachel" was the furthest out there in what subject matter you could cover on film, and that's not exactly far out.

Best director couldn't avoid New Hollywood

For those who don't know, every single member of the Academy votes on what the nominees for best picture should be. All the other categories, however, are voted on by the people who represent those branches. That means the best director category is voted on by directors, and they saw the value of the New Hollywood movement, which makes sense as it was an artistically-minded, director-driven movement. While a few best picture nominees were represented, including "Oliver!" winning it for Carol Reed, the directors' branch paid heed to some big swings.

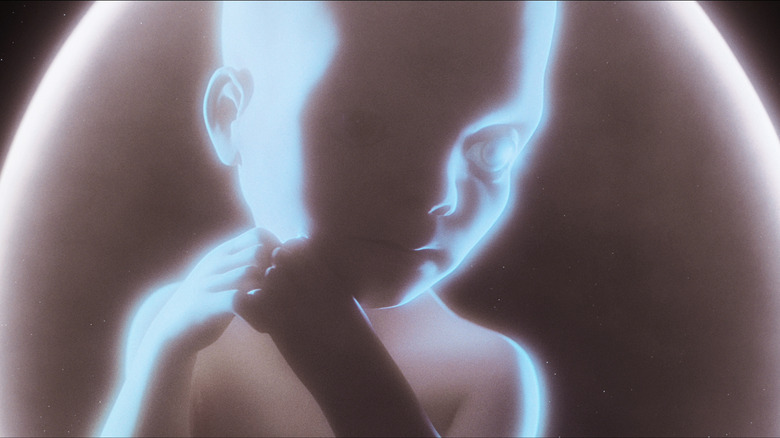

Most notably, they nominated Stanley Kubrick for "2001: A Space Odyssey." Not only was Kubrick's austere sci-fi masterpiece a major technical breakthrough and pushed the intellectual boundaries of what a genre picture like this could be, but it was also a massive hit and the second highest-grossing film of the year. It made the cultural impact the Academy of the era likes to reward, but it did it in a way that deviated greatly from its ethos, giving so much power to the filmmaker. Another big sci-fi hit tackling big themes, "Planet of the Apes," also failed to get in.

The other best director nominee not represented in the best picture category was Italian filmmaker Gillo Pontecorvo's war film "The Battle of Algiers." This gritty, anti-war picture — released in the U.S. as the anti-Vietnam movement was in full swing — went hard against Hollywood's tendency to glamorize and valorize war. The directors knew it was a staggering achievement, but the Academy as a whole said, "No, thanks."

Roman Polanski's "Rosemary's Baby" and John Cassavetes' "Faces" were also there for the taking, but they couldn't get more than nominations in the screenplay and supporting actor categories. The Academy had plenty of options, and they decided on none.

Next year, New Hollywood took over

Old Hollywood may have won the battle at the 1969 Oscars, but they would ultimately lose the war. The crown jewel of the old guard was to be Gene Kelly's incredibly expensive adaptation of the Broadway smash "Hello, Dolly!" starring Barbra Streisand. If you've ever taken a film history class, you'll know that "Hello, Dolly!" basically killed the mega-musical model Hollywood had built over the decade. Even though the film performed decently well at the box office, it cost so much that it still lost millions upon millions. It's also a pretty lackluster picture with a terribly miscast Streisand in the titular role.

It got its perfunctory best picture nomination at the 1970 Oscars, like "Doctor Dolittle" before it, but it lost the award to the true-blue New Hollywood film "Midnight Cowboy," the only X-rated film to win the award. This is a film about crushing poverty, and it won best picture, director, and screenplay. Not only was "Midnight Cowboy" in there but so was the jaunty outlaw tale "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" and the French-language thriller "Z" from Costa-Gavras.

The whole Academy could no longer ignore what was happening in the world of cinema any longer and had to respect the daring, inventive work being made. Instead of the best director category trying to represent this new wave, it solely featured it, as Arthur Penn and Sydney Pollack rounded out the category for "Alice's Restaurant" and "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?"

New Hollywood may have begun a few years prior, but 1970 cemented it to be the dominant cultural force for the movies. When even the Oscars have to relent and recognize it, that's how you know a tide has really turned.

If I picked the nominees

My personal five-film slate of nominees for the best picture of 1968 would feature just one film that actually received a nomination, and that would be "Romeo and Juliet." I already mentioned that it's my favorite Shakespearean film adaptation, as it is a film that expertly mixes the understanding of the language with the vitality and immediacy that only cinema can provide. It would be the second-place finisher to the Oscars' most egregious snub that year, "2001: A Space Odyssey," which obviously makes my five and ultimately wins. Two more aforementioned films would also make my list: "The Battle of Algiers" and "Rosemary's Baby."

As for the fifth slot, I would give that to the film that took home the best foreign language film at that year's Oscars, Sergei Bondarchuk's epic adaptation of "War and Peace." And when I say "epic," I mean EPIC. Across four parts, this thing runs a massive 431 minutes and is truly one of the most impressive and unfathomable works ever committed to film. This is a filmmaker given all the resources they could possibly desire, including from the Soviet government, and making something basically no other movie could possibly match in scope and scale.

Not only do I just prefer this five-film lineup because of how much I like the movies, but I also feel that these five do a much better job of representing how cinema was evolving at the time. This is arguably the most exciting era in film history, and the Academy wanted to play it safe. They wanted cinema to stagnate at a time of revolution, but when art stagnates, it dies. For art to thrive, it needs to constantly move forward, and more people in the business should understand that.