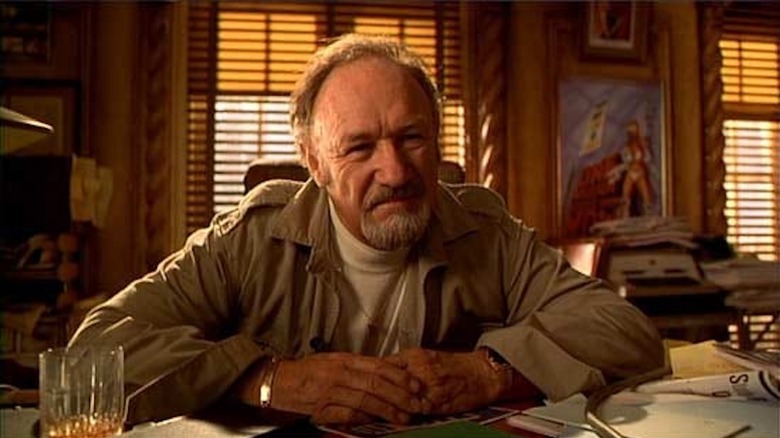

Gene Hackman Is The Best Actor Ever

Between 1964 and 2004, there wasn't a more reliably excellent actor in the film industry than Gene Hackman. He'd knock out two or three (or more!) movies a year, and even when they were dire propositions — like the Kryptonite-ridden "Superman IV: The Quest for Peace" or Bob Clark's laugh-free buddy-cop comedy "Loose Cannons" — you knew Hackman would be present and compelling. He also never went too long between watchable films, so the charge that he was phoning it in (which was also leveled at his prolific contemporary Michael Caine) never made sense.

Hackman was a true working actor. He was grateful for the gigs and took them eagerly. He knew what it was to not only struggle but to be told there is no future in this business because you flat-out stink. Hackman heard this from his instructors at the Pasadena Playhouse in the 1950s (as did his friends Dustin Hoffman and Robert Duvall, which says nothing complimentary about the company's leadership during that era), and used this as fuel to prove them embarrassingly wrong.

Hackman was so good, so immediately (he received his first Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor a mere three years after his big-screen debut in Robert Rossen's underrated "Lilith"), and so comfortable onscreen that he became a mainstay. He played his share of eccentrics, but there was nothing sweaty about his portrayals.

And it's only now that he's gone for good, having passed away at the age of 95 after retiring from acting 21 years ago, that we realize how rare of a talent he was.

The breakout role

Hackman's first bit of good fortune was appearing in "Lilith" alongside Warren Beatty. The psychological drama received mixed-to-negative reviews at the time, but Hackman impressed his co-star enough to earn the plum role of Buck Barrow in the Beatty-produced "Bonnie and Clyde." As the garrulous older brother of Beatty's outlaw protagonist, Hackman knocks the film off-center. He's a bit of a dope, but he loves his brother and has a high time accompanying him on his bank-robbing errands.

Hackman's best moment finds Buck drawing out a joke about a sick mother and a cow to the delight of Clyde as they barrel down the road. Buck is not a gifted humorist, and the punchline is hardly worth the effort he puts into the telling, but the enjoyment both men get out of it communicates their essential dimness. This gang — which includes Faye Dunaway's Bonnie, Estelle Parsons' Blanche (Buck's wife), and Michael J. Pollard's C.W. Moss — might be able to shoot straight, but there's no endgame. Bonnie is the sharpest of the bunch, while Buck and Blanche are dull drags on the haphazard operation.

They're all doomed, but Buck meets a particularly bad end, dying by bloody degrees after catching a bullet to the head. It's here that Hackman's alternately ingratiating and annoying portrayal of this doofus pays off. We pity Buck. He's a poor, uneducated Texan driven to crime by the harsh circumstances of the Great Depression. The climactic execution of Bonnie and Clyde is the scene, but Buck's death hits the hardest. At any other moment in U.S. history, he would've been a good-natured yokel pumping gas at a rural filling station. Hackman conveys the tragedy of this man's existence by just being. His effortless ability to just be would become the hallmark of his career.

The career part I

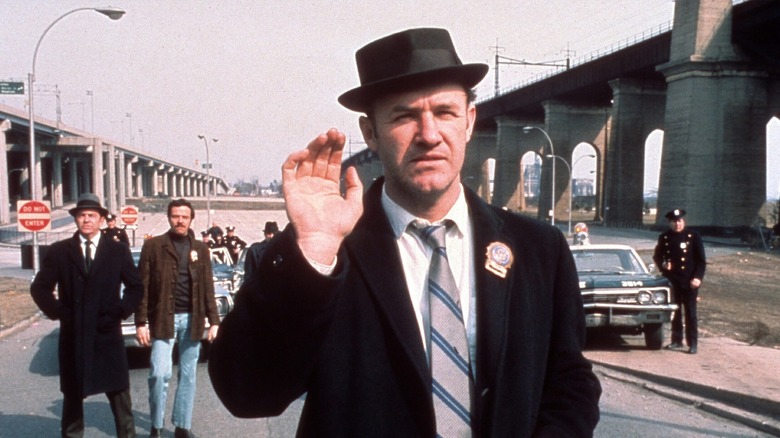

There were many historically great cinematic runs during the New Hollywood era of the 1970s, and Hackman's is about as good as it gets. He won the Best Actor Oscar for his performance as the abrasive NYPD detective Popeye Doyle in William Friedkin's "The French Connection," but this now feels like a premature coronation. He's busting his hump as Doyle, which is a lot less interesting than what he did with the oddball duo of butcher/crime boss Mary Ann in Michael Ritchie's deliriously twisted "Prime Cut" and the corrupt, jogging-obsessed cop Leo Holland in Bill L. Norton's weirdo L.A. noir, "Cisco Pike."

If you're carving a Mount Rushmore of great Hackman performances, you'd be remiss if you ignored Max Millan in Jerry Schatzberg's "Scarecrow." As a grumpy drifter who's gradually won over by the loopy ambition of Al Pacino's Lion Delbuchi, Hackman cycles through annoyance, fury, glee, and grief like it's nothing. The following year, he delivered another all-timer as surveillance expert Harry Caul in Francis Ford Coppola's "The Conversation." And, just for giggles, brought the house down as an overly friendly blind man ("You must've been the tallest in your class") in Mel Brooks' "Young Frankenstein.

Hackman reunited with his "Bonnie and Clyde" director Arthur Penn for the moody neo-noir "Night Moves," working a dour variation on John D. MacDonald's Floridian sleuth Travis McGee (he's not playing McGee, but, really, he is). He also revisited Popeye Doyle in John Frankenheimer's "French Connection II," where, via the character's cold-turkey withdrawal from a forced heroin addiction, he finds the rough texture lacking in the original.

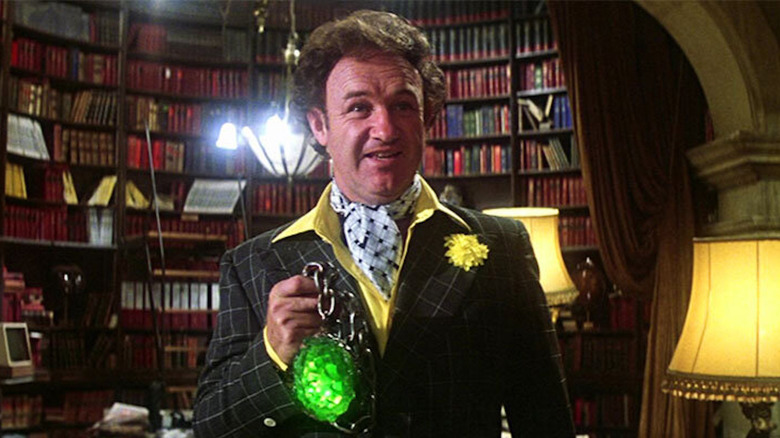

Then Richard Donner tapped Hackman to play evil mastermind Lex Luthor in "Superman," for which he was shockingly well-suited. I was five years old when I saw that film in theaters, so the broadly comedic treatment of Luthor and his cronies didn't bother me. Hackman is my Luthor. Even after the trauma of "Superman IV: The Quest for Peace," that will never change.

The career part II

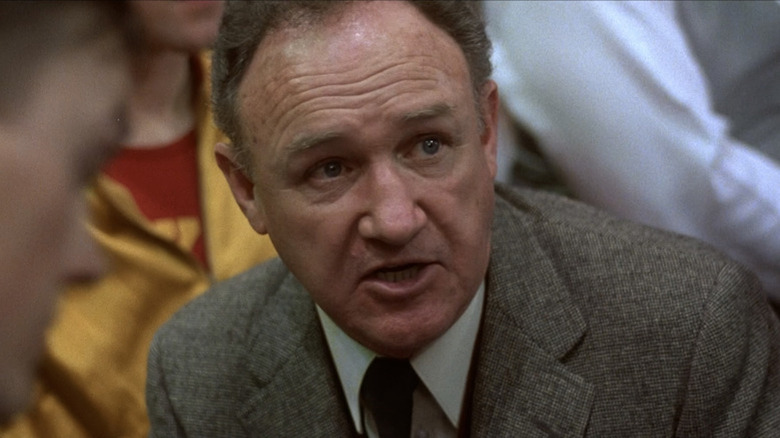

Hackman's 1980s were a skillful two-step. He danced between leads and supporting roles, and you never questioned his choices. He was at home and wholly his character regardless of the character's significance to the plot. His most underrated turn during this period might be as the fatally curious journalist Alex Grazier in Roger Spotiswoode's excellent "Under Fire." He's also especially loathsome as Defense Secretary David Brice in Roger Donaldson's Cold War thriller "No Way Out." But there's no topping Hackman's portrayal of basketball coach Norman Dale in David Anspaugh's "Hoosiers." As the fundamentals-obsessed leader of a ragtag Indiana high-school basketball team, he's stern and principled. Actually, he might be too likable. When we learn that Dale's career was derailed by striking a player, we have a hard time imagining someone this controlled flying off the handle.

The 1990s and 2000s offered more of the superb same. Hackman was by far the best thing in Sydney Pollack's bloated "The Firm," and a brilliantly hard-nosed bastard of a submarine commander, going toe-to-toe with Denzel Washington, in Tony Scott's "Crimson Tide." He cheekily paid homage to Harry Caul in Scott's underrated surveillance thriller "Enemy of the State," and had a ball as a tobacco magnate preyed upon by Sigourney Weaver's con artist in David Mirkin's "Heartbreakers."

Hackman's portrayal of the title patriarch in Wes Anderson's "The Royal Tenenbaums" should've been his crowning achievement, but he's often disengaged from the material. It's one of the only times I felt like he might've been miscast. Anderson wrote the role for Hackman and maybe that was the problem. You didn't write for Hackman, you just cast him. Clint Eastwood got this.

The defining performance

We were inclined to trust Gene Hackman. He projected intelligence. He was capable. Even when he was the villain, we willingly gave him the floor — mostly because we didn't want to piss him off.

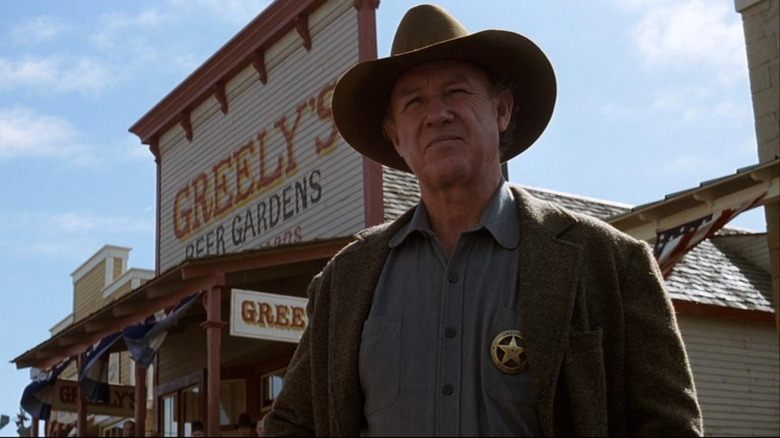

Hackman's Little Bill Daggett, the sheriff of Big Whiskey, Wyoming in Eastwood's "Unforgiven," is a man of reason. He has created a relatively civilized fiefdom in the not-yet-tamed Western United States. He has one simple rule. No guns. You surrender your iron when you cross into his city limits, and you get it back when you ride out.

In an era when there are mass shootings just about every day in America, this sounds like bliss. But there are wicked men prowling the badlands, and they can commit life-altering violence with their fists or a blade. When a young sex worker is carved up by a drunk cowboy, Bill's code compels him to keep the peace. He demands horses for the brothel's owner as recompense for the damaged human property. This is when Bill signs his death warrant.

Hackman's Bill is sympathetic. He's building a house on the outskirts of town. Poorly. But he's building it. When Bill runs Richard Harris' English Bob out of town, he keeps the gunfighter's biographer around so as to relate his version of how the West was won. Hackman's reasonableness fades. We begin to see a man who is as vicious as the evildoers from whom he purports to protect his populace. Shades of the chatty Buck, the racist Doyle, and even the pompous Luthor darken the landscape. Bill's claim to civility is that he's building a house. Hackman fully sells this lie. We see it in his panic-stricken eyes as Eastwood's Will Munny chambers the coup de grace.

Hackman's characters weren't prefabbed heroes or bastards. They're men who believed to the core of their being that they were right. And this could be as inspiring as it was frightening.

Gene Hackman was the best actor ever

No one begrudged Gene Hackman his retirement from acting in 2004, but those of us who'd grown accustomed to the actor showing up for work several times a year in movies great or terrible or somewhere in between had a hard time accepting that we weren't going to see him grace the big screen again. It didn't feel real, so some of us shrugged his decision off and figured he'd be back when he got bored with his new career as a novelist.

But Hackman, citing health issues, never felt it was worth it to step back in front of a camera, not even when Tony Scott offered him a role in the crime thriller "Potsdamer Platz" in 2010 (an unmade project that would've teamed the star with Javier Bardem, Jason Statham and Mickey Rourke). He seemed happy to write and cycle around his homes in Key West and Santa Fe (even after he was struck by a pickup truck in 2012). Yet, I know directors still made inquiries, all hoping to be the one who ensured "Welcome to Mooseport" wouldn't be the last movie on Hackman's filmography. (He did narrate a couple of military documentaries and appeared on an episode of "Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives.")

Hackman's final great performance was probably as a meticulous professional thief in David Mamet's taut 2001 thriller "Heist," but he was also quite good two years later opposite his old roommate Dustin Hoffman in Gary Fleder's sturdy adaptation of John Grisham's "Runaway Jury." I guess Hackman simply wasn't the sentimental sort, and, thus, never felt compelled to deliver a poignant swan song à la John Wayne in "The Shootist" or his hero James Cagney in "Ragtime." In the end, acting was a job — one that he did as well as anyone ever has until he just didn't feel like doing it anymore. He left us wanting more, but he also left us with so much to savor that he'll never truly be absent from our lives. Gene Hackman is forever.