How A Real D&D Campaign Between The Cast Of Honor Among Thieves Influenced The Film's Script [Exclusive]

At its heart, "Dungeons & Dragons" is an improv exercise. Put six people in a room together, give them a common goal, and sooner or later they'll embrace the fantasy so long as everybody else is playing along. There's a magic to tabletop that rewards anybody willing to roll with the punches, regardless of where the dice fall. "D&D" isn't the only tabletop role-playing game of its kind, and it likely isn't even the best. But it is the best known, which at least ensures that everybody knows what they are getting into.

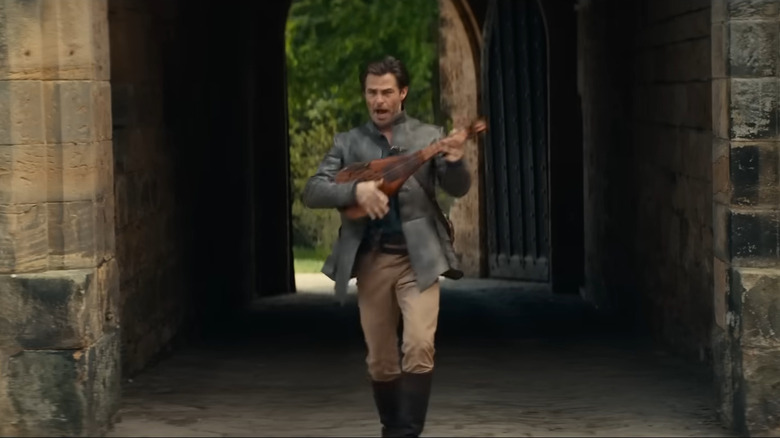

Chris Pine said at the screening of "Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves" at SXSW that "D&D" "is an actor's game." Pine plays the bard Edgin, a good-natured rapscallion of the classic school. Bards in D&D can do a little of everything; succeeding in the role means backing up teammates with songs, making smart use of low-level spells, and being the life of the party. A player must "play" the role of bard in the same way that Pine plays Edgin, just as other members of the cast embody archetypes like Sorcerer and Druid. It's enough to make you think: if Pine can be a Bard on screen, why not have him do it at the table in "D&D"? According to /Film's own Eric Vespe, that is precisely what they did. An interview with directors John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein reveals that during rehearsals, the crew ran a session of "Dungeons & Dragons" together with the cast. But it wasn't just about tabletop authenticity. During the height of the pandemic lockdown, safety regulations separated the cast and crew. To ensure that Edgin and his crew had believable chemistry on screen, Daley and Goldstein needed a good old-fashioned ice-breaker.

Relentless optimism

"They got right into it, and played their own characters," said Goldstein. "We started to see the potential and actually incorporated some of the qualities they brought to that game into the movie." Goldstein also confesses that he participated in the game as "a two-headed Aarakocra, the bird guy." Still, there remain so many unknowns. Who was Chris Pine's Dungeon Master? How long did their campaign last? Was it recorded, to be released by Wizards of the Coast as a future promotional stunt? Did Chris Pine sing in real life when his character Edgin performed bard songs? We may never know the answer to these questions. Similarly, I can't help but imagine a world where instead of playing the bard Edgin, Chris Pine instead played the real-life Chris Pine. Then we would really have "the most Chris Pine a Chris Pine performance has been in a long time."

Goldstein also spoke of the "can-do spirit" Pine exhibited throughout the campaign. John Francis Daley went further to say that "in the face of what's going on in the world right now, to have a character that exudes relentless optimism in the face of the greatest adversity is really inspirational ..." Edgin is no product of George R.R. Martin's school of hard knocks. He and his friends are heroic characters who strive to do well by others despite their own foibles. I imagine that "Honor Among Thieves" was meant to be light entertainment from the very beginning. After all, the original "Dungeons & Dragons" film from 2000 was widely hated for being an overly ambitious clunker. But Pine and company surely gave the film a push with their own efforts at the table.

Rolling dice

A cynic might say that the "relentless optimism" of "Honor Among Thieves" is less about sincerity than pragmatism. The most popular movies in the world, after all, remain Marvel's quippy superhero blockbusters. In his review at Chron.com, A.A. Dowd says that "Honor Among Thieves" "seems built for the tastes of a multiplex crowd that likes its geek fare with a side of sarcasm." In other words, the film is less notable for its good-heartedness than it is for "its canny exploitation of the Marvel model." Cast attractive actors making jokes at the expense of the source material, and you can carry the audience through any amount of fantasy exposition. It just so happens that Chris Pine and company were chosen this time rather than Robert Downey Jr.

While "Honor Among Thieves" probably is borrowing from the Marvel playbook, it's worth noting that riffing on fantasy tropes has long been a "Dungeons & Dragons" tradition. The game always owed less to Tolkien than it did to Fritz Lieber, whose "Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser" were a world removed from the likes of Frodo and Aragorn. They killed people, had sex, and occasionally came to blows. Another reference point is Jack Vance, whose adventure stories had plenty of dry humor. "Dungeons & Dragons" has been used to tell serious stories, but there's always been something absurd about its systems. Anybody who's played the game has a story to tell about mistaking a Mimic for a treasure chest, giving an NPC the run-around or even rolling a natural 1 die at the worst possible time. It's no surprise that many "actual play" podcasts like "The Adventure Zone" lean into absurdity. "D&D" is improv, and good improv is hilarious.

Friends at the table

Perhaps the best parallel for "Honor Among Thieves" is "The Dragonlance Chronicles," a trilogy of fantasy door stoppers written by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman. Per AV Club, the world of Dragonlance was originally "developed ... as part of a game module they'd created — and extensively play-tested — for D&D's parent company, TSR." Hickman himself remembers that novels were "only a 'secondary product' at best..." But Hickman and Weis believed in the world they created, and so they extensively rewrote their play sessions into the very first licensed "Dungeons & Dragons" novels. These books were loaded with cliches, including sarcastic wizards, thieving halflings and world-ending stakes. They were propelled by enthusiasm rather than style or substance. Even so, that enthusiasm made up for a lot. "D&D" has never been about originality. What mattered was that readers could live vicariously through the imagined campaigns of the books.

"Honor Among Thieves" is no different. The film stitches together fantasy epics, heist thrillers, and the Marvel formula into a Frankenstein's blockbuster. The final result lacks the coherence of organically grown fantasy epics like "The Lord of the Rings." But coherence was never the point. After all, real tabletop games are incoherent. What matters is that the players are having fun. Like podcasts and actual play campaigns, the film is yet another example of the appeal of parasocial fantasy. Chris Pine might never be your friend, just like you may only ever play D&D with Vin Diesel in your dreams. But you can imagine yourself in the room together with him and his stylish, funny coworkers for the cost of a movie ticket. How else are they supposed to encourage folks to come back to theaters?