Moon Ending Explained: Do Androids Dream Of Returning Home?

A critical darling at the time of its release, Duncan Jones' directorial debut, "Moon," leaves behind an enduring legacy of a mid-budget sci-fi premise that asks timeless and prescient questions about what makes us human. In hindsight, the ultimate "twist" in "Moon" might be fairly predictable for those well-versed in standard space isolation genre tropes, but a vague foreknowledge of the same does not dilute the thrills this experience has to offer.

In fact, the laid-back, slow-burn nature of the narrative only serves to enhance the quality of what comes next, lending a new tint to the moral dilemmas faced by Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell), an engineer stationed alone at the far side of the moon. Although Jones hones his focus on Sam's acute alienation and the disintegration of the self, "Moon" provokes multidimensional discourse about artificial intelligence, the unchecked rise of monstrous capitalist structures, and the ever-thinning line between organic and implanted memories. These themes undoubtedly evoke parallels to Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner," which also tackles thematic strands of genetic engineering and cloning, personhood, and the nature of reality.

The best way to dive into the heart of Jones' sci-fi drama is to delve deeper into Sam Bell himself, or the many versions of him that are a part of a replicated consciousness that is recycled to no end. Much needs to also be said about the unethical exploitation inherent in blue-collar jobs that offer a veneer of fairness and employee well-being, and the terrible underbelly of mega-corporations that function under the guise of the "greater good." While life back on Earth may or may not be something to truly yearn for in "Moon," Sam has every right to find out for himself.

Alone in the truest sense

The near-future setting in "Moon" doesn't seem too far off from the many possible realities that await us in the next couple of years. There's an energy crisis plaguing Earth and a multinational named Lunar Industries has managed to spearhead a mission that succeeds in finding an alternative. The isotope, Helium 3, can be found in abundance in the moon's lunar rocks and the combination of an automated enclosure and a one-man mission that lasts 3 years makes smooth extraction of the fuel possible. This man in question is Sam, who edges closer to the completion of his tenure and is motivated by the memories of life back on Earth. However, after a harvesting procedure goes wrong, Sam is forced into questioning the very fabric of his existence.

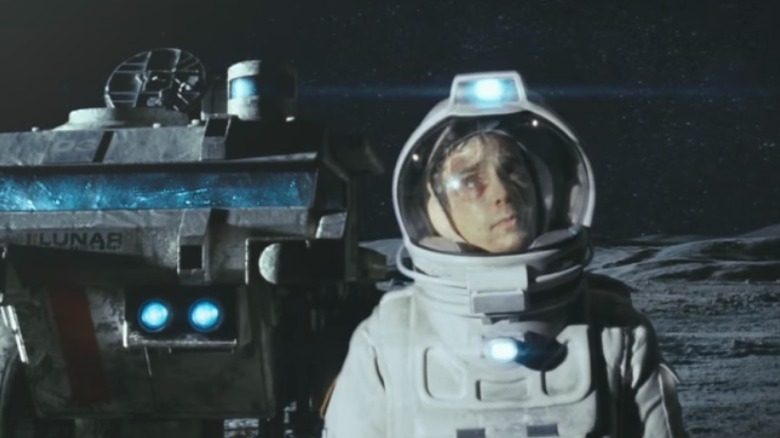

Even before this revelation, Sam leads a rather lonely existence in the Sarang Station facility, his only companion being an A.I. named GERTY. While GERTY doesn't have a structure that mimics human biology, they are sentient enough to quickly resolve hitches in the operation, which includes eliminating any threats that might expose the truth. The cross of total isolation that Sam bears makes him hyper-aware that he is a cog in the machine, but the hope of returning home sustains him through this dreary stretch of isolation.

Once this facade of normalcy shatters, Sam is left to look deep within himself and grapple with the true meaning of his existence. No one likes to feel utterly replaceable, even in an emotional sense; Sam has to contend with the fact that he is physically replaceable and is, in fact, not the "original" Sam, but actually a copy of a copy of a copy manufactured to retain real human memories, dreams, and desires.

What makes us real?

A.I. singularity is an extremely slippery slope filled with possibilities that can be both miraculous and damning, and the recent rise in A.I.-automated "art" that threatens to replace human labor only scratches the surface of this discourse. The line between inspired replication and artistic theft was blurred decades ago and is now spilling into an era of deep fakes and moderately-convincing A.I.-generated media that can easily be used to spread disinformation and bolster propaganda. "Moon" tackles related issues on a more grounded level, where clones of the "original" Sam have complex personalities based on their maker, but also harbor desires and a sense of autonomy as real as the Sam Bell back on Earth.

In "Moon," Duncan Jones seems to be underlining the fact that consciousness, whether organic or manufactured, only has meaning as long as it exhibits thoughtful individuality and yearns for something more. We're all here for a limited amount of time and no matter the legacy we leave behind, it only matters so much in the grand scheme of things. So it helps to have an absurdist mindset of deliberate meaning-making.

Yes, Sam's revolution might not matter in a system designed to deceive, where Sams that complete their tenure are disintegrated without a second thought. However, it means a great deal to the Sam who breaks the cycle of deception and ventures back to Earth. By doing so, he exposes Lunar Industries and the rotting core of a dehumanizing capitalist structure that thrives on the backs of the exploited, who might not realize they're being robbed of their humanity for the most part. Sam might only be a program, but he recognizes himself as a person, which is a stance that's as double-edged as our hyper-technological reality at the moment.

Is humanity a learned (and earned) trait?

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of "Moon" is its relentless dedication to redefining human emotions, impulses, and legacy. Being a human being in itself is not a sure-shot marker for empathy or self-awareness. Perhaps the best example of this disconnect can be traced back to the final confrontation between Roy Batty and Rick Deckard in "Blade Runner." Batty, a replicant, appreciates beauty and transience in a way that most humans in that world seem incapable of. There's something viscerally sincere about the way he's experienced his short lifespan and grappled with the loss of his fellow replicants.

Human memories and desires may be organic, but a clone with a replicated consciousness might emerge as more human than human by constantly rewiring its own circuitry and diverging from "programmed" paths of action. Sam might not have an actual family, but he yearns to see them all the time and his final actions are driven by a need to experience "home." Are Sam's inner dilemmas and desires any less valid than our own? Does his need to assert autonomy hold less meaning than the soulless machinations of a corrupt corporation run by humans? The answers are never simple.

It's also interesting how GERTY, although a program, exhibits genuine empathy for the Sam we follow most of the film, which extends beyond his instructions to offer comfort to the clones. GERTY does not have to help Sam, as he has been hardwired to thwart any threats, but instead, he chooses to take this risk for the sake of his friend. In "Moon", humanity is a learned and earned trait, exhibited during the most extreme circumstances that threaten the destruction of the self, as opposed to an inherent or organic aspect of being born a human.