Only Keanu Reeves Can Do What Keanu Reeves Does

Hollywood was in the midst of its Brat Pack fervor when the director/screenwriter team of Tim Hunter and Neil Jimenez jolted moviegoers with "River's Edge." It was the grimy, dead-souled antithesis to John Hughes' peppy tales of suburban woe. The Northern California high schoolers in Hunter's film are dead-enders who, aware of their paltry worth to society, have little value for human life. When their friend John (Daniel Roebuck) claims he's murdered his girlfriend Jamie (Danyi Deats) and takes them to see her nude corpse, which he's discarded like a dog toy next to a riverbank, they do not recoil in horror. They are at most dumbstruck, and at worst eager to aid John in covering up the crime.

We should be shocked by their lack of revulsion, but Hunter lets us hang out with these kids for a good 15 minutes before taking us to Jamie. They're future burnouts with no stated ambition outside of hooking up and getting high. The only semi-motivated member of the group is Matt, who wants to skip town for Portland. Why? "Well, because no one knows us up there."

This kid Matt, with his dark, stringy hair, clad in a jean vest draped over a leather jacket, at least senses the futility of his existence. He wants out, even if he has no idea what he'll do when he gets to wherever he's going. He's at war with his mother and hates his blossoming sociopath of a little brother, but he's not all the way gone like his unhinged best friend Layne (Crispin Glover). There's a flicker of a good person behind the loser facade, a guy looking to get right with the universe. There is the seedling of an enigma that we know and worship today as Keanu Reeves.

A rebel without a rebellious streak

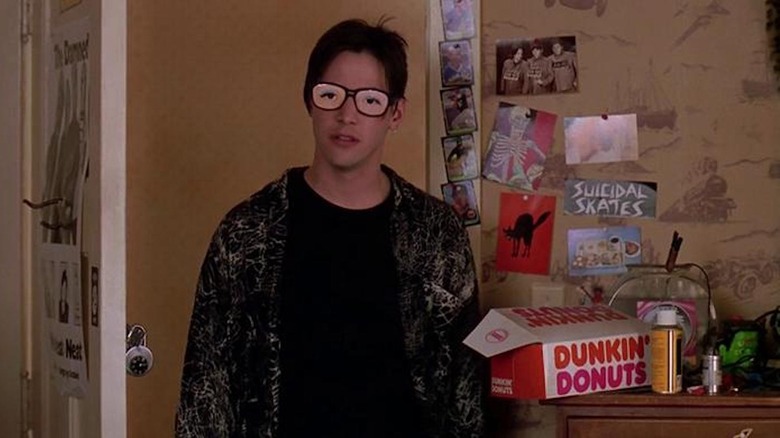

Unlike James Dean post "East of Eden," Keanu's rebel portrait in "River's Edge" didn't compel infatuated youngsters to plaster their bedroom walls with his sullenly sexy image. Keanu initially belonged to the cool kids. In the 1988 duo of "Permanent Record" and "Prince of Pennsylvania," he emitted an alternative rock type of edginess that, as the Brat Pack heartthrobs were supplanted by the vacuous, non-threatening likes of Corey Haim, Corey Feldman, and Kirk Cameron, hit like The Cure to their Bon Jovi.

Hollywood, however, had other ideas, and Keanu needed to make a movie that received a wide theatrical release. While "Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure" delivered at the box office, most critics savaged it as a brainless comedy. But OG Keanu fans rolled with it. Chris Matheson and Ed Solomon's uproarious script allowed Keanu and Alex Winter to work kind-hearted variations on the tortured (or, in Winter's case, vampiric) teens they'd played in the past.

For Keanu, it cracked open a surprising capacity for self-deprecating comedy; he'd mostly been playing the same slacker dude note since "River's Edge" (even in "Dangerous Liaisons"), so to see him exaggerate this persona only made him more endearing as a performer. He got it, and he trusted us to play along. Keanu modulated this persona as Tod, the affable loser boyfriend of Martha Plimpton in Ron Howard's "Parenthood." The way Tod delicately conveys Joaquin Phoenix's struggle with incipient puberty – "I told him that's what little dudes do" — to Dianne Wiest is inimitable. Only Keanu could hit the spacy emotional bullseye like that.

There was only one logical move for Keanu from here, and that was to make a Queer Cinema classic while starring in the most ludicrously adrenalized action movie of the 1990s.

Straddling the border of Utah and Idaho

Kathryn Bigelow's 1991 classic "Point Break" comes on hard in every sense of the phrase. It's a full-throttle action flick that pulsates with the top-this machismo that dares not speak its name too explicitly. We know precisely what's at play between Patrick Swayze's Bodhi and Keanu's Johnny Utah, and it's deliciously erotic.

Bodhi: "Ever done this before?"

Utah: "Once."

Bodhi: "Pure adrenaline, right?"

When Utah spares Bodhi during their foot chase in the Los Angeles River then rolls over and fires his pistol into the air, the source of his frustration is achingly clear. Pure adrenaline? Try pure lust.

And then there's the Queer Cinema classic. Gus Van Sant's "My Own Private Idaho" is an exquisitely instinctive adaptation of William Shakespeare's "Henry IV" duology. Keanu and River Phoenix star as a couple of street hustlers who find solace and familial love under the tutelage of William Richert's Falstaff figure. The betrayal of Shakespeare's saga stings anew when Keanu's Hal returns to inherit his wealthy family's fortune.

Phoenix is the focal point of Van Sant's film, an inveterate wanderer prone to narcoleptic episodes that break up the peripatetic nature of his life into chapters, but Keanu's Hal is, for a time, the ideal travel companion. And yet Hal is just a tourist in this world. Keanu, who is to become whatever Henry V is in Van Sant's world, understands this. He grieves for the death of their relationship, and the vagabond clan he's left behind, at the moment he is to be mourning his father's death. The emotion is real. It's always real with Keanu. And that's the key to his longevity. That and being in remarkable shape.

How to be like Keanu in an un-Zen world

I've read countless celebrity profiles of Keanu Reeves, and even the well-written ones scramble for profundity. He's one of entertainment's most enticing mysteries. What's going on under the hood?

This is not for me, nor is it for you. His tragedies are on the public record, and they suck. Life happens to us all.

Jan de Bont's "Speed" refocused the conversation on Keanu. His dude-ish demeanor was right on time for the heyday of Hollywood action filmmaking. The haircut, his chemistry with Sandra Bullock, his casual willingness to perform stunts ... after a few false starts (namely Andrew Davis' wannabe blockbuster "Chain Reaction"), he hit the sweetest of spots with "The Matrix." The distance between Keanu and his audience closed. More importantly, he helped us visualize the virtual world in which we now live. He's our righteous avatar. Our champion.

And he is now holding down the fort in the "John Wick" franchise as a hitman whose only shot at retirement is to kill his way out of the gig. This isn't Zen. Or is it? When your every encounter in the real world — be it at work, the grocery store or, god forbid, at school — is an act of life or death, perhaps Keanu's Wick is the pistol-packing co-pilot we need.

Or maybe there's a third way. Maybe we could be more like Tod.