Hedwig And The Angry Inch Ending Explained: The Origin Of Love

"Hedwig and the Angry Inch" is a movie that really helped me come to terms with myself when I first saw it over 20 years ago. Back then, I wasn't very comfortable with my looks and I often felt self-conscious about my personality when talking to people I didn't know very well. The film's message of self-acceptance really struck a chord, enabling me to take a more positive view of who I was.

Created by its star John Cameron Mitchell and Stephen Trask, "Hedwig and the Angry Inch" began life onstage as a hit off-Broadway production in 1998 before taking the leap to the big screen in 2001. The movie adaptation failed to replicate the success of the stage show, only making $3.6 million at the box office against a slim budget of $6 million. Since then, the film has become a modern cult classic, and several actors have portrayed the eponymous rocker on stage over the past two decades, perhaps the most high-profile being Neil Patrick Harris in the Tony Award-winning Broadway revival in 2014.

The film and subsequent stage versions have not been without controversy. As the discourse around transgender identities and experiences has evolved and found a stronger voice, the character has become a contentious one. In some quarters, Hedwig is still hailed as a trans icon, while some writers and critics see her as a problematic representation of a transgender individual.

As for the movie itself, I always felt that it loses focus toward the end, but then I found a fan theory that helped me appreciate how it plays out more. Let's take a look.

The set up

Hedwig Robinson (John Cameron Mitchell) is the lead singer of a rock band called Hedwig and the Angry Inch, a virtually unknown outfit touring a chain of diners called Bilgewater's. Hedwig is furious that her former lover, Tommy Gnosis (Michael Pitt), stole her songs and became a huge star. She is pursuing both a copyright lawsuit and Tommy himself: It just so happens that the Angry Inch's small-time venues are in the same cities where Tommy is performing sold-out concerts.

Between songs, Hedwig harangues her meager audience with the story of her life. Through her narration and flashback, we learn that she grew up as a "slip of a girly boy" named Hansel in East Berlin, living in a small apartment with his domineering mother. Unable to find true love on that side of the Wall, Hansel dreamed of escaping to the West in the hope of finding his other half. Enter Luther (Maurice Dean Wint), an American serviceman who persuades him to undergo gender reassignment surgery so they can marry and move to the States.

Hansel's mother arranges the operation with a shady doctor and the procedure goes badly wrong. Hansel is left disfigured with the titular angry inch, a mound of flesh "where [his] penis used to be, where [his] vagina never was." Adopting his mother's name, Hansel becomes Hedwig and moves to Junction City, Kansas, with Luther, but their marital bliss is short-lived. He leaves her for a younger boy, abandoning her in a dreary trailer park thousands of miles from home.

Alone and depressed, Hedwig finds empowerment in a blond wig and starts a band with several Korean army wives, still dreaming of finding her other half. That's when she gets a babysitting gig and meets Tommy, a naive Christian kid, and the pair form an instant connection.

The Origin of Love

"Hedwig and the Angry Inch" is packed with great songs and "The Origin of Love" is one of the strongest, providing an early showstopper and also summing up the central thesis that drives Hedwig on her quest to discover her other half. Accompanied by charming child-like animation, the dramatic tune presents a fantastical concept: In ancient times, humans were two bodies stuck together with two sets of arms, legs, and two heads facing away from each other. There were three types: The Children of the Sun were all male, the Children of the Earth were all female, and the Children of the Moon were androgynous, half male and half female.

These unlikely creatures grew very powerful, upsetting the Gods and prompting Zeus to cut them down to size by splitting them in half with his thunderbolts. Since then, we humans have been destined to spend our lives searching for our lost other halves. The idea comes from Plato's "Symposium," where playwright Aristophanes presented the notion of these eight-limbed beings and their forceful separation by Zeus as mankind's motivation for constantly seeking their soulmate.

"The Origin of Love" is crucial because Hedwig believes in this concept very deeply. It was Hansel's desire to find his other half that drove him to take Luther's dubious advice and undergo the gender reassignment surgery in the first place, and Hedwig continues the search after Luther ditches her. She even has a tattoo on her hip of a round face split down the middle, representing separated soul mates.

Hedwig is the survivor of abuse by the men in her life, starting with Hansel's father, who sexually abused him as a child. Tommy is the latest. She thought he was the one, but he betrayed her by not only leaving but also stealing their songs.

Hansel and Hedwig

When the Sydney stage version of "Hedwig and the Angry Inch" was postponed due to controversy over the casting choice, John Cameron Mitchell and Stephen Trask sought to stave off criticism by pointing out that the show isn't the story of a transgender person's journey, but that of an individual surviving trauma and coming to terms with their identity.

There is an important distinction to make because Hansel/Hedwig's tale isn't a straightforward one of a person's transition from one gender to another. Firstly, Hansel is pushed into undergoing the reassignment by Luther rather than any particular desire to change gender. Secondly, the procedure goes badly, leaving him disfigured and dysphoric.

After Luther abandons her, the song "Wig in a Box" initially begins with Hedwig singing about her dreary existence, going through the motions of putting on a wig and makeup to become "Miss Midwest midnight checkout queen," suggesting she is struggling to conform to her new female identity.

This Hedwig is one of two in the movie. The first is the more tender and wise character we see in flashbacks to her performance of "Wicked Little Town" and the first flushes of her relationship with Tommy. The fierce onstage persona we initially meet ranting at her audience is an alter ego that she gradually adopts after first donning a talismanic blonde wig, giving her an outlet for her anger and her creative side through music. This Hedwig fully emerges when Tommy rejects her, which is also when she begins to adopt a more aggressively drag-like female appearance. This is clearly not the best version of Hedwig, but it gives her an outlet to tackle her demons and use her gigs as a kind of public therapy session.

Tommy Gnosis

Hedwig is a survivor of abuse, but she in turn becomes the abuser in many of her relationships. She frequently browbeats her beleaguered Eastern band members and acts cruelly towards her second husband, Yitzhak (Miriam Shor), vindictively ripping up his passport so he can't go on tour with a part in "Rent."

Regarding Tommy, Hedwig is considerably older than the teenager when they first meet, and she totally oversteps her position of responsibility as the family babysitter by giving him a handjob in the bath. As Luther did with Hansel, Hedwig molds Tommy's appearance how she sees fit. This grooming is arguably more benevolent, presenting him the tools and confidence to become his rock star stage persona, Tommy Gnosis.

Tommy is a crucial figure in Hedwig's life, both exacerbating her feelings of abandonment before helping her find solace. Early in their relationship, Tommy tells Hedwig the story of Adam and Eve, critiquing God's decision to pull Eve out of Adam to keep him company before she eats the forbidden apple to gain knowledge. There are a few parallels here. There is a comparison between the Adam and Eve myth, with two people coming from one, and the "Symposium" tale in "The Origin of Love." Luther also pulls Hedwig out of Hansel, who is left embittered by her experience and knowledge. Similarly, Hedwig shapes Tommy to her own design, schooling him in rock music and songwriting.

Hedwig sees Tommy as the other half she has been searching for, demonstrated in the scene when she uses a mirror to reflect half of Tommy's face onto hers. That imagery continues at the film's conclusion when Hedwig, stripped of her makeup, wig, and women's clothes, mirrors Tommy's appearance. Ultimately, Tommy helps Hedwig let go of her notions of a pre-destined soulmate and reconcile the halves of her own identity.

Does Hedwig die in the car crash?

In the lead-up to the conclusion of "Hedwig and the Angry Inch," Hedwig has taken to sex work and is picked up by Tommy in his limo. They make amends while listening to their songs and Hedwig takes over at the wheel. She is distracted by a kiss and they have a car accident.

There is a theory that Hedwig dies in the crash, which I lean more towards each time I see the film. It certainly explains the dream-like quality of the final scenes and the sequence starts out like wish fulfillment akin to Rupert Pupkin's celebrity fantasies in "The King of Comedy." Tommy is disgraced and Hedwig suddenly receives the stardom she believes she deserves, appearing on talk shows and making the cover of Time Out. Could this be Hedwig's imagination creating a happy ending for herself in her final moments?

Next, she is received by an adoring crowd at Bilgewater's on Times Square, accompanied by "America the Beautiful." The American Dream has finally come true for her. Her conscience is pricked by the sight of Yitzhak sitting sullenly in a booth. If Hedwig really died in the crash, the last time she saw him was when she destroyed his passport.

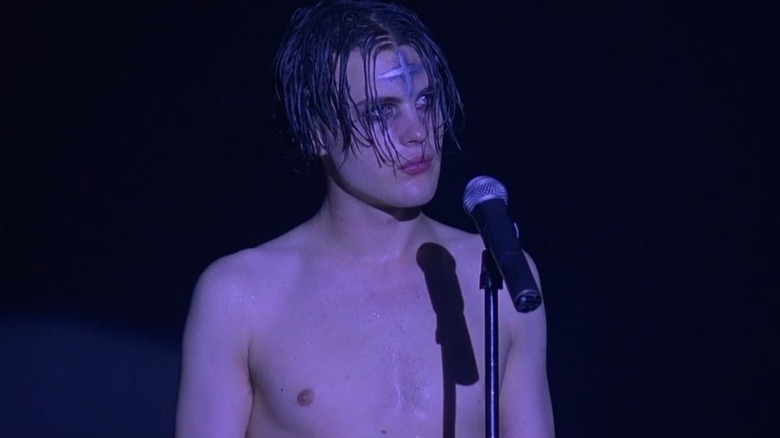

Hedwig performs two songs that are a final outpouring of sadness and rage about her present state, "Hedwig's Lament" and "Exquisite Corpse." The latter offers further hints that she may be dead as she flashbacks to the painful events of her life, such as her abusive father and Tommy rejecting her. She rips off her wig, dress, and bra, indicating that she no longer wants to play the part forced on her by Luther and the botched surgery.

Hedwig and the Angry Inch Ending Explained

If we stick with the idea that Hedwig dies at the end of the film, there is still time for reconciliation with Tommy. She appears in an empty auditorium where he sings an apologetic reprise of "Wicked Little Town." Now they are a mirror image of one another, suggesting that this version of Tommy is a manifestation of Hedwig's consciousness. He sings, "And there's no mystical design, no cosmic lover preassigned," words that allow her to finally let go and come to terms with who she is.

We flip back to Bilgewater's, now decorated with glowing white, a further clue that the finale is set in the afterlife. Hedwig, relinquishing her belligerent stage presence, is once again the gentle and wise person we saw before the alter ego emerged. She symbolically hands her blonde wig to Yitzhak. Hedwig no longer needs it and the gesture releases Yitzhak from her toxic grasp and enables him to embrace his own dream of becoming a drag artist.

Hedwig sings "Midnight Radio," an anthem for the "misfits and the losers." It is the only song in the film's repertoire that isn't about Hedwig and her experiences, a poignant rallying call to anyone who has also had difficulty accepting who they are.

Lastly, we see Hedwig/Hansel walking down an alleyway naked, reborn in a state "more than a woman or a man," ready to face life (or the afterlife) as who they really are without apology, disguise, or makeup. An animated sequence shows the two halves of Hedwig's tattoo becoming one; supporting the death theory, this only occurs after the two segments smash together and fall over, apparently dead. As "The Origin of Love" plays again the film leaves us, whichever way we identify, with a message that we don't need anyone but ourselves to become whole.