Eraserhead Ending Explained: A Surrealist Nightmare About The Anxieties Of Fatherhood

"Believe it or not, 'Eraserhead' is my most spiritual film," said surrealist auteur David Lynch in an interview, and this moment has become a meme template over the years. When asked to elaborate, the director smiled and simply said no in the most David Lynch way, emphasizing his philosophy of subjective interpretation and a refusal to "explain" his art. This outlook remains true to the essence of Lynch's oeuvre — most of his work is rooted in dream or nightmare logic, meant to be experienced instead of dissected or understood. Abstract ideas form chilling vignettes of what can only be described as grotesque or deeply surreal, such as his intensely hallucinatory "Inland Empire," which still defies explanation beyond the core themes that drive the film. Perhaps, that is the point of it all: Dreams often do not make sense, even to the dreamer, but act as portals to the subconscious and reveal absurd truths about the self and the other.

Keeping these aspects in mind, this piece is less of a didactic explanation of "Eraserhead" and more of a curious speculation about the hellish industrial wasteland in which the film takes place, where anxiety and agonies emerge as default emotions that govern its characters. The grotesque lies at the heart of "Eraserhead," where premature spermatozoon-like creatures are birthed into the void and every aspect of everyday life is marked with a brand of surreal ugliness. After all, this is a film whose foundational concept revealed itself to Lynch in a daydream about a disembodied head being taken to a pencil factory, an idea that the director allowed to gestate and flesh out in Kafkaesque ways, much like the heavily bandaged, Eraserhead baby that feels out of place in the film's soulless, post-apocalyptic world.

Sonic dissonance

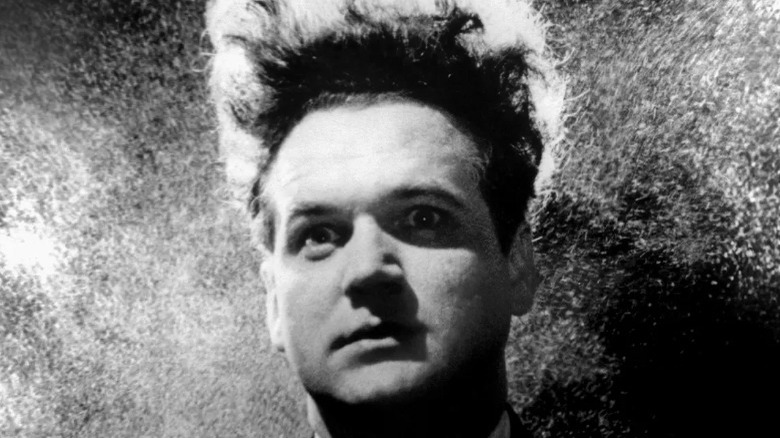

Before delving into the narrative, I would like to talk about the film's stellar sound design, which heavily lends to the sense of relentless discomfort that defines it. The story's industrial setting, although reflective of some corners of postmodern society, emerges as alien due to the way sound accentuates the threats of living in such a landscape, where safe spaces are a myth and emotions are as deformed as the infant that seemingly falls from the sky. While some industrial sounds overpower certain scenes, a majority of the events are layered with an unnerving, low-level background noise that follows Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) wherever he goes.

Music has always been a full-fledged functional facet in Lynch's world, be it in the form of Angelo Badalamenti's haunting soundtrack that directly defines the inner landscapes of "Twin Peaks" or the crucial significance of Roy Orbison's "In Dreams" that acts as a turning point in Lynch's "Blue Velvet." For "Eraserhead," Lynch worked alongside Alan Splet to carve out the visceral sound design, while working closely with Fats Waller and Peter Ivers, who composed original pieces that underlined a sense of Kafkaesque claustrophobia, reminiscent of the menacing, bureaucratic world of Joseph K. in "The Trial."

Lynch also uses sounds to induce anxiety or anticipation in audiences, using clanks, hisses, and subtle foreboding notes to set the stage for allegorical strands, such as when Spencer stares at the radiator and hears steam escaping, but this is meant to allude to his inner world and not his tangible reality. This is what makes the film's horrifying aspects more effective, as familiar sounds offer a mirage of normalcy, only to be undercut by an endless, hopeless nightmare with no beginning or end.

Anxiety, the root of unease

Spencer is a stand-in for the everyman, and the industrial town he lives in does not have any unique features to set it apart from similar urban spaces. Spencer does things that seemingly appear like everyday tasks — he picks up his grocery, talks to the woman who lives next door, and visits his ex-girlfriend's parents' house for dinner. However, the mechanics of his reality are strange from the get-go, as every interaction and social circumstance follows dream logic, such as when he is asked to "carve" a live chicken that writhes, spurts blood, and looks deformed in a certain sense.

Both Spencer's inner world and immediate reality are driven by a feeling of anxious unease, the kind one might feel at the onset of an anxiety attack, where the world seems to close in on the person experiencing it. Confusion and disorientation are a part of the experience, further heightened by Spencer feeling unmoored by the presence of a child that he suddenly has to take care of.

Even before the infant is revealed inside Spencer's apartment, he seems perennially anxious and on edge when conversing with Mary X (Charlotte Stewart) and her mother, who makes sexual advances toward Spencer before revealing the news about the baby. Although we might never experience exactly what Henry does, we are urged to form our personal rendition of this ultra-specific nightmare, based on our unique individual anxieties that plague our waking dreams and everyday reality. The jarring use of sound and imagery to shift scenes and evoke strong emotions highlights the ugliness of existence, and this is when we cross over into deeply introspective, spiritual territory. When a wailing, spore-covered baby is thrown into the mix, things are bound to feel more disjointed than usual.

Bearing the weight of fatherhood

While most peculiarities in the unnamed world of "Eraserhead" are never questioned or addressed, the infant is presented as so unnatural and alien that Spencer immediately questions whether it can even be called a baby or not. After X and Spencer take the baby to the latter's apartment, they are at a loss when it comes to taking care of the creature, who wails incessantly and refuses to consume anything. X leaves soon after, driven insane by the ordeal, and Henry is left to shoulder the weight of fatherhood on his own. These anxieties manifest in baffling nightmare sequences, involving Mary (Judith Anna Roberts), along with Spencer's interpretation of heaven and a disturbing infant-stomping sequence.

Paranoid resignation haunts Spencer from this point on, as he struggles to nurse the baby back to health, but succeeds to an extent. This makes the film's ending especially shocking, as Spencer does something heinous to his own creation after he removes its bandages and stabs its delicate organs as they fall apart. Is Spencer so disgusted by his daily drudgery and alienation that he murders his own flesh and blood, who he deems as a reflection of his inner deformities? Or does Henry simply manage to overcome his fear of fatherhood by killing a nightmarish vision of a mangled child that represents the worst anxieties that accompany this mantle?

The answers are complex, as this bleak act of murder can be condemned or rationalized as per individual worldviews and belief systems, which seep into our dream states and vice versa. Themes of conception and sexual anxiety are prevalent here, especially what comes after the act: The need to be responsible for a feeble, impressionable life in a world where taking care of one's inner impulses can be a burden.

Hell, corruptibility, and redemption

The crux to understanding the ending of "Eraserhead" (at least in an abstract, fragmented sense) is the relationship between Spencer and the dreary world he lives in. Nothing in this world feels organic, especially with its heavy emphasis on the sonic industrial drone that haunts the entire narrative. The humans in this world, although idiosyncratic, often blend into one another, including Spencer, who is as nondescript and nonchalant as it gets. The final act of infanticide is the only instance in which he exercises some form of active resistance, in a desperate attempt to regain control of a sterile existence in an urban cityscape that sprouts lifeless plants and borderline-uninhabitable living spaces.

The Radiator Woman in Spencer's visions is the only entity removed from soulless mechanization, which is why she's present in Spencer's idea of heaven. Here, heaven is an unattainable dream, far removed from hellish reality, and this safe space can only be experienced in bits and fragments. Hope and truth are elusive for Spencer, as he is too mired in the absurdities of everyday Sisyphean tasks, where one can only imagine oneself to be happy. There is a sickness inherent in this daily toil, which goes hand-in-hand with human corruptibility and ugliness, with the baby being an extension of Spencer's tortured psyche.

After Spencer seemingly kills his own darling, along with the worst aspects of himself, he experiences peace. The mechanical sounds grind to a halt, replaced by a white noise that represents the sanctity of silence. After Spencer embraces the Radiator Woman, he is bathed in white light, something that can only be dreamed of when one is born in the depths of hell. Thus Spencer is born anew, embarking on a spiritual journey after earning redemption. But will this dream last?