Repo Man Ending Explained: The More You Drive The Less Intelligent You Are

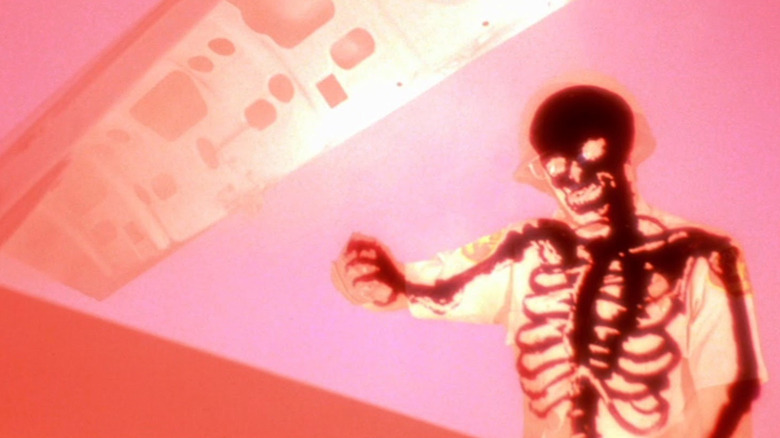

Out on the edge of the Mojave Desert, a cop pulls over a speeder. Arrogantly approaching the apprehended speeder's car, he casually asks the driver what's in the trunk. The driver (Fox Harris) ominously replies, "You don't want to look in there." This, of course, makes the cop suspicious, so he decides to look anyway. When the trunk swings open, a horrifying red light spills out. The cop attempts to shield his eyes, but the red light quickly vaporizes his body. Only the cop's boots are left behind, his smoking remains dispersing into the desert breezes. The speeder pulls away.

So begins Alex Cox's seminal 1984 punk rock epic "Repo Man," one of the best movies ever made. "Repo Man" stands in deliberate, wrathful defiance of capitalism, a big F.U. to the almighty dollar. Like a punk ballad itself, "Repo Man" is a ball of concentrated rage, designed to lash out at anything that dares call itself mainstream, mellow, or successful.

"Repo Man" takes place in a world not so different from our own, where Reagan's capitalism and the rise of televangelism are pushing humanity out of the world. Emilio Estevez plays the embittered punk rocker Otto — sounds like "auto" — who unhappily works at a grocery store. The products in the store are all sealed in white, generic boxes with blue stripes on them, bearing no aesthetic or identity. In the world of "Repo Man," humanity has devolved to serve products, and products themselves barely exist beyond labels.

In a low-rent capitalist nightmare like this, everyone is in debt. And the only reason people fear debt is because of the Repo Man. What greater statement in a world of consumption than a job taking stuff away?

The more you drive, the less intelligent you are

Looking over the popular media of the 1980s, one finds a lot of iconography from the 1950s. This makes perfect sense, as those who were kids in the '50s had finally grown up into filmmakers. As such, there were time travel movies about going back to the '50s, a movie about a 1958 Plymouth Fury magically turning an '80s teen into a '50s greaser, a musical fantasy starring characters from "The Wild One," a nostalgia piece about '50s adolescents trekking to see a dead body, and a black comedy about a '50s child suspecting that his parents may be feeding him human flesh. The 1980s saw a rise in conservatism in the spirit of the '50s, and artists responded to venerate or lambaste the post-war years that the country was clearly looking to.

"Repo Man" specifically takes aim at 1950s car culture. Thanks to a post-war manufacturing boom, commuting cars became a needed item for every suburban home. To accommodate the expansion of the car industry, ancillary car-related businesses began appearing as well. Drive-through restaurants facilitated the rise of fast food, and drive-in theaters facilitated teens' ability to have sex in public (the legends are all true). But as things depressed in the 1980s, all the glamor and economic advantages of having a car tarnished. The junkyards grew, and vehicles became filth-spewing boat-shaped coffins in which to smoke cigarettes and fall behind on bills. That's certainly the way Harry Dean Stanton, character actor extraordinaire, looks to be using his car in "Repo Man."

With the glamor and the money all gone, the junkyards come hunting. Otto finds that stealing cars back from their owners is a dandy way to make a profit, but also to operate on the fringes of a society he finds so unappealing.

Think about a plate of shrimp

The plot of "Repo Man" sees Otto getting a job as a repossessor and being taught the ropes by some tough-as-nails mentors in the form of Stanton and Sy Richardson. During the course of his job, he gets a new lease on nihilism, growing power as a punk outsider. Otto already hated society, spending a lot of his time listening to The Circle Jerks and Black Flag. Being a repo man was a job that provided the intensity he sought. Stanton dictates the movie's ethos: "Ordinary ****in' people. I hate 'em." The common man doesn't exist, security sucks, the world is a leech, money defines us for the worse, and intensity is all that matters.

Otto catches wind that there is a particularly valuable Chevy Malibu — the repo fee would be $20,000 — driving around his dingy, just-outside-of-L.A. neighborhoods, ripe for repossession. This is the car seen at the film's introduction, the one with something unusual in the trunk. The driver is clearly mad, and doesn't seem to fathom what's inside. It may be a nuclear bomb, but it's eventually made clear that it's the radioactive corpse of a space alien.

The ending of "Repo Man" sees Otto finally getting his hands on the radioactive car, despite the best efforts of other repo men, the government, and revolutionaries to stop him. In the climax, the entire Malibu begins to glow green. Sitting at the wheel is Miller, a local kook played by Tracey Walter. Miller previously decried driving as a frivolous activity, a relic of the 1950s. "The more you drive, the less intelligent you are," he says. As it so happens, he was an alien. He's able to drive Otto into the sky and away from Earth once and for all.

Always intense

When the Malibu glows green, it vaporizes anyone who comes close. Televangelists are turned to ash. Many die. When Miller gets in the car, he beckons to Otto, and Otto gets in too.

This is a moment of freedom. Not only did Otto receive his prize, but he got much more. Like a f***-you-inflected version of "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," Otto uses extraterrestrial means to find his home. As a punker, he wanted to leave human society behind. As a capitalist, he wanted to steal a car and be set for life. Miller provided him with both.

"Repo Man" argues that 1950s glamor is a bygone myth, and that the grease of a car's undercarriage is all that remains. Our quests to earn money, get a job, and pay off our bills are all attempts to achieve what we really want: escape from humanity. Delving into the systems as they exist is no solution. Working a dead-end job at Package Mart will not fulfill you. Money will not fulfill you. Love and sex will not fulfill you. Religion will not fulfill you; Christianity had been reduced to its lowest state in the 1980s in the form of evangelical TV preachers who hatefully ranted against gay people.

Alex Cox gives us a fantastical solution. The symbol of physical and economic mobility in the United States, the car, will contain deep within it the means to leave forever. Maybe that's what 1950s car culture should have been all about. Not the status, not the ability to consume hamburgers on the go, not even the necessity. Perhaps they should have always been about escape, about getting out.

Otto got out. Good job. This world sucked anyway.