Michael B. Jordan's Favorite Anime List Might Be A Sign Of A Bigger Problem

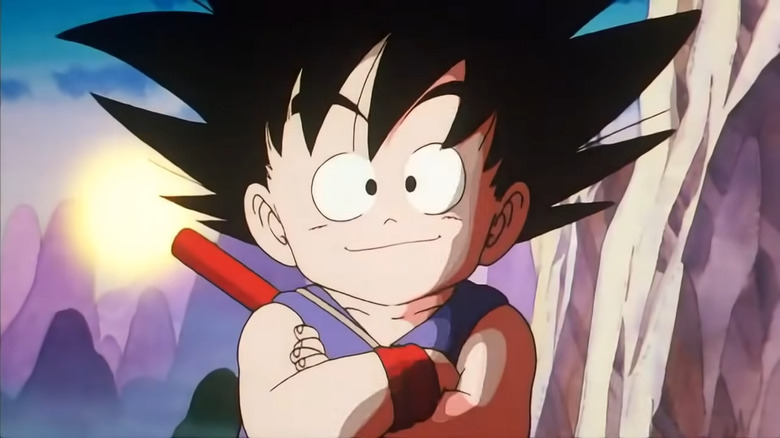

As part of the press tour for his new film "Creed III" — whose fight scenes bring the franchise into anime territory — Michael B. Jordan listed his five favorite anime series on BBC Radio 1: "'One Piece,'" "Dragon Ball," "Naruto," "Bleach," and "Hunter x Hunter." These are all worthy picks, even though it "would take the average person over 957 hours ... to complete Jordan's top five anime recommendations," as Isaiah Colbert said at Kotaku. "One Piece" has lasted for over a thousand episodes. "Dragon Ball" remains one of the most popular anime ever. "Naruto" featured some of the wildest fight scenes in anime history, while "Bleach" at its best was just cool. "Hunter x Hunter" is messier, spanning two adaptations and a source comic that has yet to finish. But its creator Yoshiharu Togashi has over 3 million followers on Twitter, and his dedicated fans haven't given up on him yet.

These five shows follow a particular formula. Each is about a boy who wants to become the best at his chosen hobby. He overcomes challenges and makes friends while angling for the top. Eventually, he reaches a plateau, only to realize that even stronger foes lie in wait. This is the bread and butter of shonen anime and manga — Japanese for boys' comics. It's a structure that makes perfect sense for a boxing film like "Creed III," which by its nature is all about overcoming the limits and fears of the body to win in the ring. But casual filmgoers may not recognize that Jordan's five favorites are linked by theme and publication history. All five started as comics published in Weekly Shonen Jump, the best-selling comics magazine in Japan.

Jump start

Japanese publishing giant Shueisha launched Shonen Jump in 1968 to compete with Weekly Shonen Sunday ("Urusei Yatsura") and Weekly Shonen Magazine ("Hajime no Ippo.") It distinguished itself from the competition by what Takeo Udagawa, in his cultural history "Manga Zombie," calls the "Great Two" system. The first was "watertight contracts binding artists exclusively to the publication." The second was "comprehensive reader surveys." Each magazine carried a poll in which readers voted for their favorite comics and characters. If artists fared poorly, they had to change or face expulsion. That's not to say Jump was against racy or experimental material. One of its first big hits was "Harenchi Gakuen," a controversial sex comedy by "Devilman" creator Go Nagai. Per Mainichi Daily News, "school PTAs across Japan campaigned strongly against it." But the comic sold well, and kids wrote in to say their parents "were reading much raunchier stuff than [Nagai] was producing."

Jump had other successes in its early days, including the comedy series "Gutsy Frog" and the boxing saga "Ring ni Kakero." But it wasn't until the 1980s that the magazine truly erupted. Akira Toriyama's "Dr. Slump" was the most innovative comedy of its time and inspired a 1981 anime series that lasted for over 200 episodes. In 1983, "Fist of the North Star" combined martial arts with "Mad Max" costuming to phenomenal effect. Then came Toriyama's 1984 series, "Dragon Ball," the blueprint for all subsequent action comics published in the magazine. Its paneling, story structure, and stylized designs inspired a generation of artists. Toriyama himself would always prefer the anarchic "Dr. Slump" to the comparatively structured "Dragon Ball." But there was no doubt what Jump's readers loved best.

Slam dunk

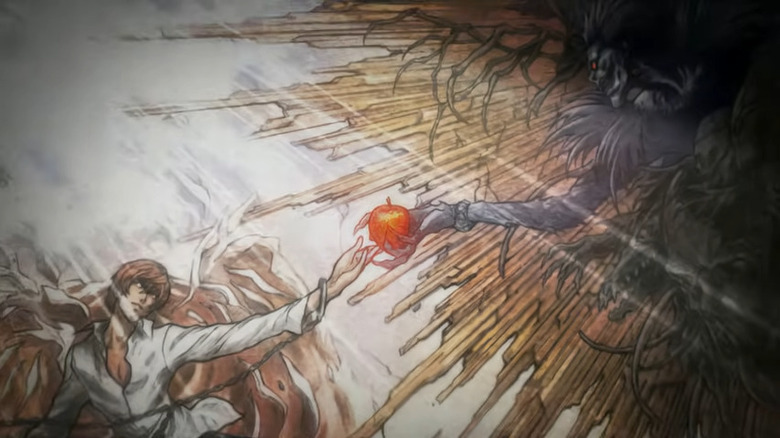

In the following years, Shonen Jump became a cultural force. 1990's "Slam Dunk" made Japanese teenagers want to play basketball. 1999's "Hikaru no Go" taught kids how to play Go. 2003's "Death Note" led to a moral panic when children started buying death notebooks of their own. Each of these comics inspired anime series that were similarly popular and remain influential today. Last year's "The First Slam Dunk," directed by the comic book's creator Takehiko Inoue, just won animation of the year at the Japan Academy Film Prize Association. A new live-action "Death Note" series is now in the works at Netflix, with the involvement of "Stranger Things" showrunners The Duffer Brothers. Even "Hikaru no Go" was adapted into a terrific Chinese drama in 2020.

Shonen Jump was also exported to the U.S. The very first English-language issue of the magazine was published in 2005, featuring popular series like "One Piece," "YuYu Hakusho," and "Yu-Gi-Oh!" Toonami propelled anime adaptations of "Dragon Ball Z" and "Naruto" to superstar status. Fans watched their favorite shows on television, bought the DVDs, and read collected volumes in the graphic novel section of Borders. (Or they pirated them, but that's another story.) Legal anime streaming became increasingly accessible and inexpensive through sites like Hulu, Funimation, and official YouTube channels. Crunchyroll especially became popular following its transformation from a pirate site to an industry-sanctioned streaming company in 2009. Today, Shonen Jump anime is among their most popular offerings. Crunchyroll listed "Jujutsu Kaisen" and "My Hero Academia" as the most-watched anime on its platform by folks in North America in 2020.

Web comics

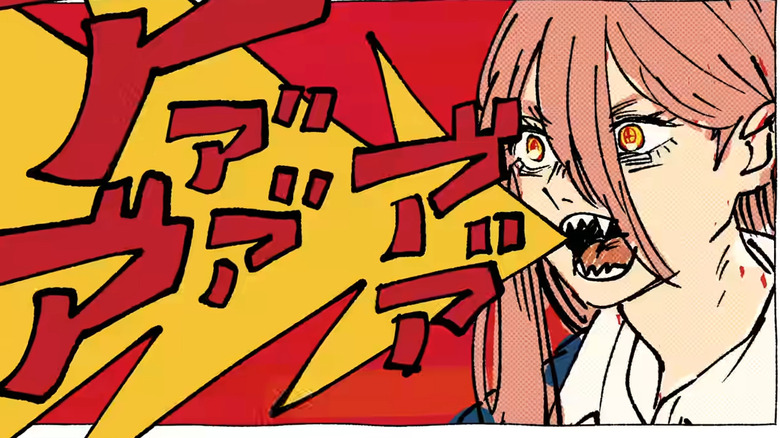

Shonen Jump has continued to evolve in recent years. A mobile app released in 2019 made thousands of issues accessible to readers for just $1.99 a month. While the price increased this year to $2.99 a month, it's still one of the best deals in comics. Many of Jump's biggest contemporary hits, such as "Spy x Family" and "Akane-banashi," hail from the web-based Shonen Jump+ branch rather than the magazine itself. The artist that best embodies the spirit of Jump+ is Tatsuki Fujimoto. While his series "Chainsaw Man" began serialization in the magazine, his debut "Fire Punch" was serialized in Jump+. Fujimoto followed the first part of "Chainsaw Man" with two Jump+ exclusive one-shots, "Look Back" and "Goodbye Eri." After a hiatus, the second part of "Chainsaw Man" has since been released on Jump+. Artists like Fujimoto have benefited from the looser content restrictions of Jump+, allowing for weirder and wilder material that might otherwise be out of place next to "One Piece."

Anime based on Shonen Jump properties have also changed. In the early 2000s, series like "Naruto" and "One Piece" ran for hundreds of episodes alongside the ongoing manga. Today, while some ongoing series like "Boruto" remain, others like "My Hero Academia" are made and released seasonally. The quality of each episode is relatively consistent, and in the case of "One Piece," exceptional. Films based on Shonen Jump properties have also been unusually successful in recent years. "Demon Slayer: Mugen Train" rode the popularity of its previous TV adaptation and the stresses of post-Covid Japan to become 2020's biggest film. While previous Shonen Jump films were non-canonical playgrounds for animators to go wild, "Mugen Train" was a canonical new installment based on manga material.

A single genre from a single publisher

Considering all this good news, you might question the headline: "A bigger problem? What bigger problem?" I have no bone to pick with Michael B. Jordan's taste. The five series he picked are five of the most successful entertainment franchises. But the manga and anime world has always been broader than Shonen Jump. The best-selling manga series of all time in Japan include "Golgo 13" (Big Comic), "Detective Conan/Case Closed" (Weekly Shonen Sunday), and "Doraemon" (CoroCoro Comic). Not to mention comics published in shojo (girls) magazines, like "Boys Over Flowers." The longest-running anime series in history is not "Naruto" or "One Piece" but "Sazae-san," a gentle family comedy that has aired 2,684 episodes as of January 2023. Shonen Jump remains a big player with many famous and artistically successful anime adaptations to its name. But it is not the only game in town.

By comparison, manga and anime fandom in the U.S. are cast in the image of Shonen Jump. Young millennials grew up watching "Naruto" and "Bleach." These shows have since become nostalgia icons due to careful marketing by companies like Crunchyroll and Toonami. The massive popularity of these series has also led younger audiences to seek them out as their first anime experiences. While some folks eventually move beyond Jump, many are satisfied to live in the house that "Dragon Ball" built. Evan Minto, the co-founder of the online manga service Azuki and an ex-Crunchyroll employee, recently commented on Twitter that "it's wild seeing so much stuff like this where anime basically means a single genre from a single publisher." This raises the question: is America in the middle of an anime boom or a Shonen Jump boom?

Attack on Jump

Before I raise anybody's hackles, I should add that many of the most popular anime abroad has nothing to do with Jump. "Attack on Titan," the series that inaugurated the legal anime streaming boom in 2013, began in the pages of Bessatsu Shonen Magazine. (Shonen Jump rejected his initial one-shot, which I imagine haunts the magazine to this day.) "Fullmetal Alchemist," which began my love affair with anime and manga, ran in Square Enix's Monthly Shonen Gangan. Not to mention "Sailor Moon," which remains a generational touchstone despite being poorly served over the past few years. Or "Pokémon," which is its own beast entirely.

Other mediums have inspired popular anime adaptations in recent years. Light novels, a vein of anime-inspired young adult fiction published in Japan, inspired anime franchises like "Sword Art Online" and "Monogatari." The web fiction site Shosetsuka ni Naro (Let's Become a Novelist!) has been highly influential recently due to high-profile adaptations of "That Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime" and "Mushoku Tensei." Crunchyroll partnered with the Korean comics publisher Webtoon to adapt "Tower of God" and "The God of High School" in 2020. Meanwhile, the success of "Castlevania" on Netflix led to a glut of animated video game adaptations. One of these, "Cyberpunk: Edgerunners," walked away with anime of the year at Crunchyroll's 2022 Anime Awards.

Knights of the zodiac

Still, "popular anime" is inevitably cast in the mold of Jump: the boy hero who must train rigorously to become the best, make friends and overcome increasingly powerful foes. It doesn't help that anime streaming has a presentist bias. Ongoing series are heavily promoted, while older shows are allowed to sink into obscurity. Outside of "Fullmetal Alchemist" and the rare original series like "Cowboy Bebop," older shows that survive to be marketed to the next generation of anime fans inevitably hail from Shonen Jump. Meanwhile, in comics, bestseller charts are dominated by Jump's catalog. Nineteen of 20 entries in NPD Bookscan's 2022 top-selling manga list are from Shonen Jump. Four of the five manga volumes that made it to The New York Times's graphic books and manga list for February 2023 are Jump comics.

Shonen Jump is, of course, popular outside of the U.S. as well. Per Comics Beat, a 2022 consumer survey by GfK and Livres Hebdo included "One Piece," "Spy x Family," and "Naruto" among France's five most popular manga series of the year. The 1986 anime adaptation of "Saint Seiya," a series about heroes beating each other up while wearing mythological armor, remains a smash hit in Europe and South America. But Shonen Jump did not necessarily mark the beginning of anime fandom in these countries. It was instead 1974's "Heidi, Girl of the Alps," 1976's "3000 Leagues in Search of Mother" and others of their ilk that were first exported to foreign markets. These were not the exciting action series of today. Instead, they were children's stories dubbed into multiple languages as part of Nippon Animation's "World Masterpiece Theater" initiative.

Pressing buttons

There are reasons to be nervous about Shonen Jump's grip on the imaginations of anime and manga fans abroad. The first and most pressing is the magazine's historical role in corporatizing manga production. In "Manga Zombie," Takeo Udagawa writes manga have always been "works of art and commercial products at one and the same time." Even so, the epochal success of Jump in the '80s represented something new: the mastery of manga as a commercial product, shifting the balance of the whole industry in the process. "The only expertise publishers now cared about was how to sell manga in greater volumes," Udagawa says. "What mattered was pressing the reader's buttons with pinpoint accuracy."

Another reason is that despite its significant female readership, Shonen Jump remains a sexist institution. In 2019, an anonymous Twitter user quoted HR from the magazine's publisher Shueisha. While a woman could be hired as an editor at Shonen Jump, the HR representative said, "You have to understand the hearts of boys." This sounds eerily similar to the words of former Ghibli producer Yoshiaki Nishimura, who told The Guardian that compared to women, "men ... tend to be more idealistic — and fantasy films need that idealistic approach."

Yet both statements are quaint compared to Jump's history. In 2020, "act age" writer Tatsuya Matsuki was charged with committing "a coerced indecent act on a female middle school student." In 2017, "Rurouni Kenshin" creator Nobuhiro Watsuki was charged with possession of child pornography. In 2002, Mitsutoshi Shimabukuro was caught paying a 16-year-old girl for sex. Not only has "One Piece" creator Eiichiro Oda continued to give Watsuki a platform, but Shimabukuro went on to publish popular series like 2008's "Toriko" in the magazine. Only Matsuki has so far been blacklisted.

Friendship, effort, and victory

The emphasis on "friendship, effort, and victory" in Shonen Jump inevitably stifle the type of stories that are told. Naruto and his friends might struggle with cruel authority figures in the same way that Deku and his friends discover the contradictions of the superhero world in "My Hero Academia." But these hierarchical systems are almost always proven correct in the end. Naruto learns that his father was the Fourth Hokage and that his journey to becoming Hokage is an act of inheritance rather than an underdog story. Endeavor, the father of Shoto in "My Hero Academia," is introduced as an abusive father only to slowly change his ways throughout the series. While men are allowed to be complex, women are rarely afforded that same privilege. With some exceptions, such as "Jujutsu Kaisen," the bar is on the floor when it comes to the handling of female characters in Shonen Jump comics.

Jump+ has allowed for comparatively varied storytelling. "Akane-banashi," for instance, has a rare female heroine for a Jump comic. The second part of "Chainsaw Man" follows the story of Asa, who is uniquely weird, off-putting, and relatable. (Kotaku's Sisi Jiang called her "the 'femcel' we need, not the one we deserve.") Even so, I can't help but worry about the potential reader who catches up with "Chainsaw Man" only to search in vain for similar comics on the Shonen Jump app that are comparably weird. Sure, Jump's website features "Dandadan" by former Fujimoto assistant Yukinobu Tatsu. Other unconventional titles, like "Takopi's Original Sin" and "Oshi no Ko," may be found on Shueisha's Manga Plus website.

A world beyond Jump

But the world of manga is so much bigger than "Shonen Jump." You don't need to look that far afield to find comics in the vein of "Chainsaw Man." The work of Shuzo Oshimi, whose breakthrough "Flowers of Evil" was published alongside "Attack on Titan" in Bessatsu Shonen Magazine, is similarly preoccupied with adolescence, sexuality, and the apocalypse. Elsewhere, Weekly Shonen Sunday has been serializing Q Hayashida's "Dai Dark," which features grotesque monster designs and a quirky sense of humor "Chainsaw Man" fans might recognize. Hayashida's earlier series, "Dorohedoro," was adapted into an anime produced by "Chainsaw Man" studio MAPPA in 2020. All of these works are now available in translation for English-speaking audiences. They might not be available in a web app, but you may be able to find them at your local library.

The great strength of Japanese manga is its variety. There are comics about cooking, business management, and soap. There are award-winning series for children and adults filling every possible niche. Many of these do not sell as well as comics published in Shonen Jump or other heavy hitters of the manga industry. But many sell just enough to establish themselves as viable alternatives. Each small success empowers the business as a whole. This same dynamic can be seen in countries like France, where comics are treated as a medium rather than a genre. Shonen Jump is famous there, but they've also published avant-garde artists like Atsushi Kaneko. Not to mention that France has its share of comic legends, including Jacques Tardi and Manu Larcenet.

Death note

By comparison, the comics industry in the U.S. was heavily damaged by the reign of the Comics Code Authority. It's only in the past decade that a varied, sustainable comics culture has grown up around graphic novels for middle-grade and young adult readers. Of course, these works straddle the boundary between art and commerce that Takeo Udagawa wrote about in "Manga Zombie." But they at least cover a wider range of subject matter and techniques than Shonen Jump. If today's manga publishers want to capture the heart of this new generation raised on Raina Telgemeier and Gene Luen Yang, they should be licensing series beyond the action comics that made Jump famous. Publishers like Seven Seas Entertainment and Denpa Books have been doing just that.

A comics and anime industry built on Jump and its ilk are on borrowed time. "Demon Slayer" and "Jujutsu Kaisen" may be entertaining works of commercial art in their own right. But the commercial and critical success of "Chainsaw Man" abroad indicates fans exist who want something spicier than the magazine's average. Should Shonen Jump fail to meet that demand, these viewers may very well cast Jump aside. The anime world, as well, stands on thin ice. Anime adaptations are as popular as ever, but original series are few and far between. Because conditions in the industry are so bad, there are not enough skilled animators to meet demand. A recent shortage of contract workers has led to several anime series this winter being delayed mid-season. An industry where smaller productions eat each other for resources while larger ones become stultifyingly conservative is no industry at all.

One-inch tall barrier

For manga and anime to truly be viable abroad, they must thrive outside the walls of Shonen Jump. Thankfully, there are comparative examples to draw upon in the manga publishing industry. One of the most popular horror comics artists in the U.S. is Junji Ito, who has transformed from a cult artist to a publishing sensation. Viz has released so much of his back catalog to meet this demand that they've arguably diluted the appeal of his work. Not everything he's produced is at the same level as "Uzumaki," after all. But other publishers like Kodansha have capitalized on Ito's success by publishing work by other Japanese horror artists, including Masaaki Nakayama and Kanako Inuki. Even small publishers like Star Fruit Books have gotten in on the action, returning the likes of Hideshi Hino to print.

In a speech at the 2020 Golden Globes, "Parasite" director Bong Joon-ho said that "once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films." You could say the same for anime and manga. There is so much more on offer than just Shonen Jump. Sure, the app is convenient. I suspect the magazine's editors have more respect for the art form than their harshest critics admit. The best anime adaptations have enough great episodes to dissect for years. Not to mention that revisiting old favorites with friends can be fun in its own right. But Shonen Jump should be the beginning of your journey through the medium, not the end. Great wonders exist elsewhere. You just have to be willing to open the door and travel that world without roads.