George Lucas Knew The Star War Prequel Trilogy Couldn't Meet The Fans' Expectations

Richard Marquand's sci-fi blockbuster "Return of the Jedi" was released in theaters on May 25, 1983. It was the third or fourth film in its series (depending on whether or not one counts "The Star Wars Holiday Special" as a canonical chapter, which it is), and was a clear sign that Hollywood had officially evolved away from the intense, heady, adult dramas that were in vogue throughout the 1970s. After "Return of the Jedi," high-concept, big-budget, mainstream sci-fi movies became a dominant trend, and kids of the 1980s were so deeply marked by the decade's genre entertainment that it's all still being remade and re-marketed to this day. (One will have no trouble finding "Ghostbusters" merch, for instance.) This was the world "Return of the Jedi" wrought.

There were a few animated shows and two TV movies in 1984 and 1985, but there wouldn't be another "Star Wars" feature film until the release of "Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace" in May of 1999. Readers in their 40s will likely recall the period clearly. It was a time when the VHS market boomed, and "Star Wars" fandom was born in earnest. Fans could now watch the films dozens of times, memorize tiny, minute details, and develop deep affinities for characters that have only a few lines of spoken dialogue.

A lot of "Star Wars" fandom was academically bolstered in 1988 by the release of "The Power of Myth," a filmed conversation between Bill Moyers and mythology expert Joseph Campbell, who indicated that the popularity of the space epic was due to its adherence to ancient storytelling tropes. Thanks to "The Power of Myth," "Star Wars" became the subject of endless study and discussion in perpetuity.

When 1999 rolled around, anticipation couldn't have been higher.

The Phantom Menace

In a 1999 interview with Empire, director and "Star Wars" creator George Lucas acknowledged that whatever he made would disappoint fans. There was no possible way to live up to the hype.

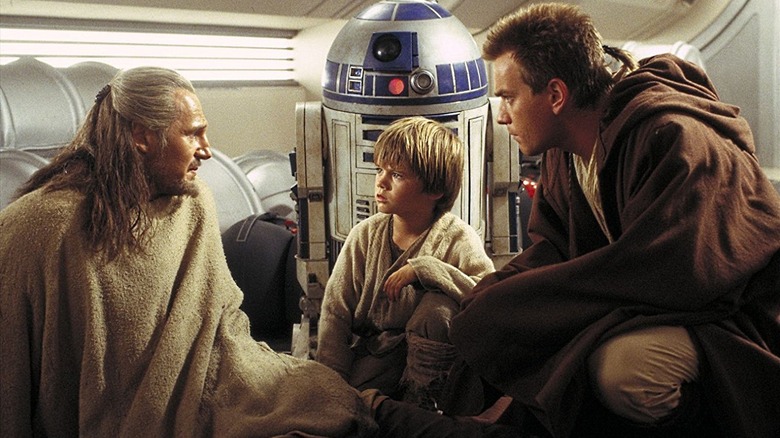

Those alive in 1999 will recall the pre-"Phantom" frenzy. "Star Wars," which had become one of the most avidly worshiped pieces of pop ephemera, was going to see its first theatrical release in 16 years. People waited outside theaters, sleeping on the sidewalk for weeks, eager to be the first to buy tickets. Many spent hours downloading the preview (this was pre-streaming) and watched ad infinitum. The film came out to favorable (if lukewarm) reviews, but after the initial rush died down, many fans found that "The Phantom Menace" wasn't growing on them the same way the earlier "Star Wars" films had. "The Phantom Menace" eventually grew into one of the most hated pieces of franchise entertainment, and online pundits have devoted many, many hours to its deconstruction.

Lucas, in accepting that he wouldn't be able to please everyone, wrote the film specifically to his own whims, and not to cater to fans or the marketing department. When asked what he did to make "The Phantom Menace" palatable, Lucas said:

"Basically I didn't. I kept it as it was originally intended. You can't play too much to the marketplace. It's the same thing with the fans. The fans' expectations had gotten way high and they wanted a film that was going to change their lives and be the Second Coming. You know, I can't do that, it's just a movie. And I can't say, now I gotta market it to a whole different audience. I tell the story. I knew if I'd made Anakin 15 instead of nine, then it would have been more marketable."

What's marketable

1999 George Lucas knew what was and what wasn't marketable. He is, after all, the founder of an entire "Star Wars"-based toy industry. But he also knew to follow his heart as a screenwriter. Sure, he could have aged up the central characters, but, he continued:

"[T]hat isn't the story. It is important that he be young, that he be at an age where leaving his mother is more of a drama than it would have been at 15. So you just have to do what's right for the movie, not what's right for the market."

Hence, a nine-year-old Anakin Skywalker. Lucas wanted Anakin to be an innocent, not a teen badass or a broody adolescent. Lucas also gave Empire readers a little peek into what the then-unmade "Episode II" would entail, explaining that it was to be a love story. Lucas acknowledged that romance is rare in an adventure series like "Star Wars," and was perfectly willing to challenge longtime fans' notion as to what the franchise could be:

"[B]y the nature of it being a love story, it's less of a kids' movie because they don't like to sit through all that yucky stuff. But it's still aimed at the same age level, so it's going to be a real challenge for me to get through that part. And then the third film is very, very, very dark. It's not a happy movie by any stretch of the imagination. It's a tragedy. People think of the 'Star Wars' movies as happy movies. What they're going to do about a tragedy, I don't know. It will probably be the least successful of all the 'Star Wars' movies ... But I know that."

One can admire Lucas for staying with his ideas.

The reputation

As mentioned, "The Phantom Menace" was eventually pilloried. Toxic fans were particularly cruel to actors Jake Lloyd and Ahmed Best, who played the young Anakin and the Gungan Jar Jar Binks, respectively. Both actors had their mental health severely impacted. Eventually, both "Star Wars: Episode II — Attack of the Clones" and "Star Wars: Episode III — Revenge of the Sith" opened to enormous numbers, but fan reception was notoriously unenthused. They weren't the least successful "Star Wars" movies, but they were among the most lambasted.

What happened is George Lucas seems to have had a different view as to what "Star Wars" was than the film's many fans. Lucas wanted to tell stories reminiscent of the corny, melodramatic adventure serials of his youth, not realizing his own movies supplanted said serials as the new standard of the genre. Fans seemingly wanted more typical adventures, and didn't care for romances, clunky dialogue, or tales of trade route taxation. The rise of the Empire was via strange, dull politicking, not military force or shows of evil. For many, the films merely weren't exciting. It also didn't help that the revolutionary CGI effects were unappealing to look at.

But then, maybe Lucas was right to stick to his guns. By 2015, and the release of "Star Wars: Episode VII — The Force Awakens," many came out in defense of "The Phantom Menace," with /Film's own Caroline Cao declaring it the catalyst for her own "Star Wars" fandom.

Lucas knew that disappointment was part of "Star Wars" DNA, so he followed his whims. Eventually, he came out on top.