Alien: 12 Xenomorph Facts That Are From Another Planet

No monster has struck fear into the hearts of moviegoers quite like the Xenomorph. The titular creature in Ridley Scott's 1979 sci-fi masterpiece "Alien" — as well as the sequels, prequels, spin-offs, video games, comic books, and novels that followed — is a killer beyond compare in science fiction, and today stands as one of the genre's most recognizable antagonists. And while it's fair to say that the franchise has been subject to a few ups and downs over the years, the spine-chilling power of the Xenomorph itself has never been less than total.

How much do you really know about Ellen Ripley's archnemesis, though? Is there more to this horrific beast than what you've seen on screen? Well, yes: Fittingly for a creature designed by a legendary surrealist, the history of the Xenomorph is as strange as the monster is scary. From the earliest concepts to those endless variants to a real-life insect that's a little too familiar for comfort, here are some of the most fascinating facts about the true star of the "Alien" saga.

Making a monster

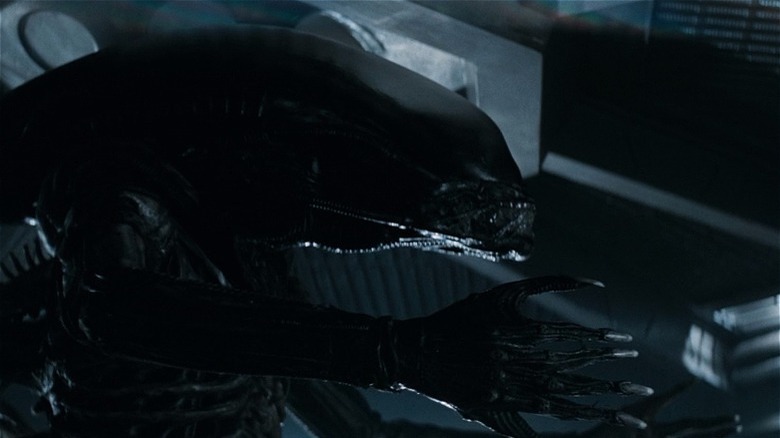

The Xenomorph is an absolute triumph of design. While the alien of "Alien" doesn't appear much in the original movie, the few glimpses we're given tease the genius of H.R. Giger's unique aesthetic. Just look at it: the elegant, almost beautiful carapace; the mechanical flourishes on the exoskeleton; the sheer horror of those pharyngeal jaws; the slime that covers it almost head to toe; even the disturbing sexual imagery that the Xenomorph's appearance evokes — clearly, the combined efforts of Giger, Scott, and "Alien" screenwriter Dan O'Bannon produced a monster that more than deserves its hallowed place in the cinematic canon.

The earliest ideas for the Xenomorph's look were remarkably less impressive, however. In a 2017 interview on the podcast "WTF with Marc Maron," producer Walter Hill revealed that Robert Aldrich, one of the directors approached to helm "Alien," simply suggested shaving a trained orangutan. Later, artist Ron Cobb came up with a design for a spotty, hook-handed Xenomorph that looked a little like a cross between a T-Rex and the prawns from "District 9." These ideas obviously aren't quite as terrifying as the final design, and we can all count our lucky stars that Scott and O'Bannon decided to hire H.R. Giger early during the film's production ... unless, of course, you really wanted to see Sigourney Weaver blast a monkey into space.

Skulls of the surrealist

Giger was already a renowned painter by the time he was brought onto the "Alien" crew, but his contribution to the film turned him into a horror icon. Scott chose Giger for his project based on a single artwork in the designer's illustrated book, "Necronomicon." The painting, titled "Necronom IV," will be immediately recognizable to sci-fi fans today: It is, essentially, a depiction of the Xenomorph. There are a few key differences, as Giger gradually tweaked the design in order to translate his art to the silver screen, but "Necronom IV" is clearly the foundation for the monster we all love and fear.

That wasn't the end of Giger's contribution to the creation of the Xenomorph, though, as he also helped build the creature's first life-size model. At some point, you may have heard the infamous rumor that Giger placed a real human skull in the Xenomorph's carapace — and the good/horrifying news is that this is, apparently, absolutely true. Giger confirmed as much in a 2009 Time Out interview, adding: "Don't ask me where I got it." Still, we've got a pretty good idea about that too: In the commentary for 1985's "Return of the Living Dead," Dan O'Bannon says that he was told Giger had sourced his skulls from India; he also claimed that "Texas Chainsaw Massacre" director Tobe Hooper once informed him that it was possible to purchase human remains as part of the country's so-called "bone trade." There doesn't seem to be any concrete proof regarding these claims, of course, but it certainly adds something to the bizarre mythos surrounding the Xenomorph's conception.

The man in the rubber suit

If "Alien" has an unsung hero, it's Bolaji Badejo. The man in the Xenomorph suit was more than a mere mannequin on whom Giger's design could be transplanted — his unsettling, sinister, almost ethereal sense of movement gave the Xenomorph much of its grace, and no doubt made an indelible contribution to both the creature's initial impact and its enduring legacy.

Badejo himself came more or less out of nowhere. Peter Ardram, a casting agent on "Alien," met Badejo, a six-foot-10 Nigerian artist, as they drank in a pub in Soho, London. He called up associate producer Ivor Powell and told him he'd found exactly what they were looking for. Scott agreed, and before long Badejo was taking mime classes and undergoing physical training to prepare for his first (and, as it turned out, only) on-screen role.

Filming proved tough for Badejo: He had never been on a set before, he spent half the shoot covered in KY Jelly, and it was near-impossible to see or move in the Xenomorph suit. According to special effects supervisor Nick Allder, however, he never complained once. "He did keep inside himself, quite a bit," Allder later told CNN. "Being on a film set must have been quite strange for him. To have been the center of attraction ... it was a bit of a shock to him." After filming wrapped on "Alien," Badejo returned to Nigeria, where he opened an art gallery. He died of sickle cell disease in 1992, at just 39 years old.

The final death

You probably remember how "Alien" ends: Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), the last survivor of the USCSS Nostromo, escapes the ship's self-destruction aboard a small shuttle. She soon realizes that the Xenomorph is on board the shuttle too, forcing her to climb into a spacesuit, flush it out using gas, and open the airlock door. Ripley shoots the Xenomorph with a grappling hook, sending it hurtling into the void of outer space, before using the ship's engines to see it off once and for all. Horror movie endings don't get much more satisfying.

Originally, Scott had a much different fate in mind for both Ripley and the Xenomorph. During an interview with Entertainment Weekly (via Esquire), the director revealed that the movie was supposed to end with the Xenomorph claiming Ripley as its final victim. "I thought that the alien should come in," he said, "and Ripley harpoons it and it makes no difference, so it slams through her mask and rips her head off." The Xenomorph would then operate the shuttle's controls, mimicking the voice of Captain Dallas (Tom Skerritt) as it signs off the Nostromo's last log. According to Scott, the first Fox executive arrived on set within 14 hours of learning about this intended ending and threatened to fire him on the spot. Scott relented, and Ripley's death was undone — proof, if ever it were needed, that executive meddling isn't always such a bad thing.

What's in a name?

Here's a fun fact about Xenomorphs: they're not actually called "Xenomorphs." Or, at least, that's not the name that was intended for them. In "Alien," the creature is never explicitly named, with most characters referring to it only as "it" or an "alien." Meanwhile, the franchise's DVD and Blu-ray releases dubbed monster "Internecivus raptus," the Latin term for "murderous thief," and a few comic books have used the term "Linguafoeda acheronsis," meaning "foul tongue of Acheron."

So where did the name "Xenomorph" come from? As it turns out, it all comes down to a simple misunderstanding. In "Aliens," when Lieutenant Gorman briefs Ripley and the colonial marines, he tells them that there's been no contact with the colony on LV-426, and suggests that "a xenomorph may have been involved." Rather than being a name for the species itself, the Greek word "xenomorph" literally means "strange form" — and Gorman is simply describing the alien as an alien, albeit in a somewhat haughty manner. Fans ran with the moniker regardless, most likely mistaking Gorman's line as a specific styling of the franchise's main monster. It seems to have stuck, though: Although nobody in any "Alien" movie has ever used the capital-X "Xenomorph" to refer to the creature, the word has since appeared on various items of merchandise, including in the 2014 tie-in book "Alien: The Weyland-Yutani Report" (in which the species is called "Xenomorph XX121"), and in the credits of 2017's "Alien: Covenant."

Cameron and the Queen

Although the "warriors" in James Cameron's 1986 sequel "Aliens" are nearly indistinguishable from the original Xenomorph, the movie did introduce a new addition to the creature's mythology: the Queen. Ripley encounters this towering matriarch of the Xenomorph brood during the escape from Hadley's Hope, and their showdown aboard the USS Sulaco makes for one of the franchise's most iconic moments.

Naturally, the Queen is supposed to be much larger than the other Xenomorphs, meaning that, when it came to building a full-sized animatronic for the "Aliens" shoot, Cameron and special effects legend Stan Winston had their work cut out for them. The first step — a "proof of concept" for the design — seems a little rougher around the edges than the finished product. In 2021, the Stan Winston School posted behind-the-scenes footage of Cameron and Winston's "Garbage Bag Test," which utilized a puppet made of garbage bags, foam core, and ski poles.

Cameron's contribution to the Xenomorph Queen didn't end in the director's chair, either: He also provided the screeching, breathing, and various other noises featured in the final film, using nothing but a microphone and his own voice. This is nothing new for Cameron, who has made off-screen appearances in a number of his own movies, including "The Abyss," "True Lies," "Titanic," and "Avatar."

Eggmorphing

One of the most famous deleted scenes in the original "Alien" sees Ripley come across the Xenomorph's nest during her escape from the Nostromo. Here, she finds Captain Dallas and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton). Dallas is barely alive and poor ol' Brett has been partially subsumed into one of the alien's eggs, so Ripley uses her flamethrower to spare them both a fate worse than death. This all-kinds-of-disturbing scene gained such popularity with fans that later home video releases reinserted it. However, it also threw up a tricky issue for both fans and other franchise creators.

Long before it was released to the public, the "Eggmorphing" scene was well-known to "Alien" fans, having been mentioned in a number of tie-in books as early as 1979. Then, in 1986, "Aliens" revealed that Xenomorph eggs are actually created by a queen. So what does the contradiction between these forms of reproduction mean? Could the two methods possibly co-exist in the "Alien" universe? And what's the point of a queen if any random Xeno can produce its own eggs? Esoteric as they may be, these questions have dogged the franchise's fan community for many years.

Later films in the series didn't fuss much with providing the answers. The 1992 novelization of "Alien 3" claimed that Xenomorphs are capable of both methods of reproduction, depending on individual circumstances, while also suggesting that eggmorphing might actually be a method of producing a queen. "Alien: The Roleplaying Game" attempted to reconcile these differences by stating that a queen's eggs are stronger and quicker to produce. As with so many problems like this, it's probably easiest to say that the solution is whatever you want it to be.

Menagerie of murder

The Xenomorph from "Alien" might be what you'd call the "classic" version of the creature, but the franchise has concocted a wide array of variants over the years. Some of these are almost as recognizable as the original, such as the warriors and the Queen from "Aliens," while others, such as the Deacon in "Prometheus" or the Praetomorph in "Alien: Covenant," rank as more obscure. Of course, a few are just downright naff. Case in point: the awful CGI dog Xenomorphs in "Alien 3," and whatever the hell appeared at the end of "Alien Resurrection."

Dig deeper into the world of "Alien," and you'll find yet more twists on the classic Xenomorph formula. Many of these are born out of a specific host, such as the Predaliens of the "Alien vs. Predator" mini-franchise and the Tarkatan Xenomorph, a playable fighter in the 2015 video game "Mortal Kombat X." At the same time, "Aliens versus Predator 2," mentions a Xenomorph Empress, while other video game releases have included yellow and red versions of the alien. Perhaps the strangest version of all is the Bodyburster, which features in the 1997 comic book series "Aliens: Kidnapped." Otherwise known as an "Axolotl Xenomorph," this bizarre mutant is a fully-grown chestburster that never matured past the larval stage — think of it like the caterpillar from "Alice in Wonderland," if Alice was having the literal worst day of her life.

Alien 2: On Earth

"Aliens" may be widely regarded as both the perfect successor to "Alien" and one of the greatest sequels of all time, but someone actually beat James Cameron to the punch six years prior to its release. In 1980, Italian director Ciro Ippolito released "Alien 2: On Earth," a low-budget and entirely unauthorized sequel to Ridley Scott's original movie. "On Earth" is weird in many ways: For one thing, it inexplicably unfolds in the 1980s, despite the plot revolving around an alien egg from the Nostromo that ends up on Earth. The egg itself, essentially a blue rock, also looks nothing like the ovomorphs found aboard the Derelict. The most egregious difference from Scott's version? The alien itself.

The antagonist of "Alien 2: On Earth" is a deadly extraterrestrial that gestates inside the body of an unsuspecting human host, but the resemblance ends there. Rather than emerging from the host's chest cavity, this alien bursts out of the face, and the creature it grows into is a slimy, blood-soaked blob that is about as far from H.R. Giger's design as you could possibly get. It also possesses the ability to shapeshift and assimilate other beings, making it more like the alien from "The Thing" than anything else — although, considering that movie came out in '82, it seems probable that Ippolito drew inspiration from "Who Goes There?", the 1938 John W. Campbell novella on which it was based. Unsurprisingly, "Alien 2: On Earth" and its drastic reshaping of the Xenomorph was not exactly a runaway success, and the arrival of "Aliens" annihilated what little impact it made on the sci-fi canon.

Xenomorph kills the Marvel Universe

The Xenomorph is most famous as a movie monster, but it has been almost as prolific in comic book history. The "Aliens vs. Predator" franchise is probably the best indication of this: Beginning with the 1989 comic "Dark Horse Presents" Vol. 1 #34, the Xenomorph/Yautja match-up has proved to be a recipe for success for comic book writers, video game designers, and filmmakers alike. In fact, the original "Aliens vs. Predator" comic book line spanned 30 years and countless stories.

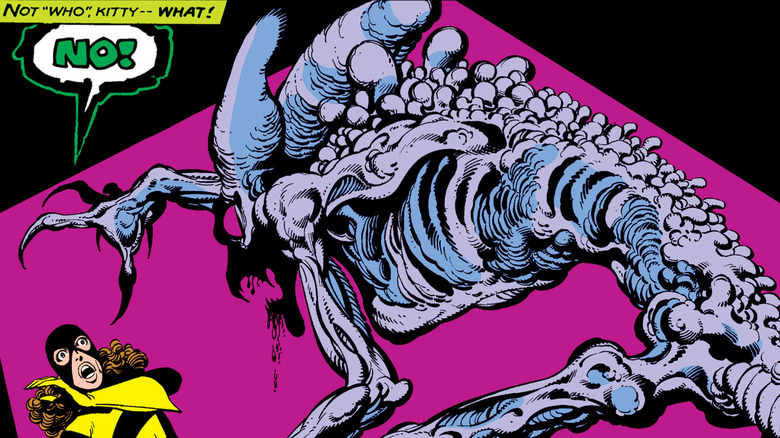

That's not the end of the Xenomorph's role in the comic-book world, either. For example, the 1997 two-issue title "Batman/Aliens" sees the Dark Knight taking on a hive of Xenomorphs in the Guatemalan jungle. 1995's "Superman vs. Aliens," meanwhile, has the Man of Steel embark on an adventure into deep space, only to come face-to-face with an alien infestation on a distant remnant of Krypton. Even Marvel attempted to recreate the success of "Alien" long before the Dark Horse/DC crossovers began. 1980's "Uncanny X-Men" Vol. 1 #143 follows Kitty Pryde as she's stalked through the X-Mansion by a N'Garai, a gigantic demon that takes more than a few cues from the Xenomorph's design.

In 2020, Marvel Comics purchased the rights to the "Alien" and "Predator" comic franchises, and while the company began a run of "Alien" comics a year later, times have changed since 1980. So, don't expect to see the Hulk battle a Xeno queen anytime soon. Still, it's a testament to the Xenomorph's enduring legacy that its design was inspiring new stories just a year after the release of "Alien" ... and has continued to do so for over four decades.

The wasp of death

You might think that the Xenomorph's life cycle is too far-fetched and gruesome even for reality — but you'd be horribly, horribly wrong. Indeed, when it comes to the stuff of nightmares, Mother Nature has very much still got it.

In 2018, scientists in Australia (where else?) found a new species of parasitic wasp that eats its victims from the inside. Here's how it works: The adult wasp injects its eggs into living caterpillars. Over time, the eggs hatch into larvae, which eat away at the insides of the caterpillar, before breaking out of its body, growing into adult form, and carrying on the hunt for more hosts. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? The wasp's cycle is so similar to that of the Xenomorph, in fact, that the researchers who discovered it paid tribute to its name: Dolichogenidea xenomorph.

This isn't entirely a case of life imitating art, however. Dolichogenidea xenomorph was the latest in a group of insects known as parasitoids, which kill their hosts to complete their life cycles. The term was coined back in 1913, meaning it's almost certain that these insects inspired Dan O'Bannon's screenplay. It's certainly no coincidence that the book "Natural Enemies: An Introduction to Biological Control" states that the movie's script "could have been written by a parasitoid biologist."

Angels and demons

From the moment that first chestburster emerges from Kane's (John Hurt) chest in "Alien," the purpose of every single Xenomorph has been unwavering: kill, kill, kill. As the android Ash (Ian Holm) tells Ripley, it's the ultimate murder machine, "unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality."

But why do Xenomorphs kill in the first place? What drives their hatred for humans? For years, it seemed that the answer was nothing more than simple, animalistic bloodlust, but a throwaway line in the 2012 prequel "Prometheus" turned all that upside-down. As Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace), Charlie Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green), and the crew of the Prometheus explore the ruins of the ancient base on LV-223, they find the decapitated corpse of an Engineer. Shaw uses her carbon reader to determine the date of the Engineer's death: "2000 years ago, give or take." So what happened about two millennia prior to the events of the movie, which takes place in 2089?

Yes, it seems unlikely that this timeframe is a coincidence: "Prometheus" appears to be telling us that the Engineers were preparing to bring their bioweapon stockpiles to Earth around the time of the death of Jesus Christ. This would account for the about-face in the Engineers' motives and explain, in Shaw's own words, "what we did wrong." It stands to reason, then, that mankind's creators intended to use the Xenomorph to wipe out life on Earth as punishment for the crucifixion of Jesus — who could well have been an Engineer himself. You could even argue that, rather than mindless insectoids or savage hunter-killers, Xenomorphs are the closest thing the universe has to actual, living demons.

Sweet dreams.