The Big Lebowski Sums Up Everything You Need To Know About The Coen Brothers

When "The Big Lebowski" hit cinemas 25 years ago, most people had no idea what to make of it. Sure, it made immediate fans of some, but the movie was met with a heavy dose of bewilderment. In the critical community, this confusion came from the fact that Joel and Ethan Coen were coming off of their Oscar-winning film "Fargo," released just two years earlier. Though they had made plenty of celebrated films prior, "Fargo" was this unimpeachable, darkly funny thriller that could satiate your average audience member and already established Coen fan alike. They crystallized something in that film that made it seem like the brothers would just be building off of its foundation afterward.

But that's not what happened. The Coens took a sharp left turn and made an offbeat stoner comedy that riffed on the classic tropes of film noir. They had become "serious" filmmakers with hardware to show for it, and I think some people felt betrayed after latching themselves to the directing duo when they immediately pivoted and made something seemingly so unserious.

All this time later, we now can see the greater scope of Joel and Ethan Coen's careers, and them deciding to make this movie no longer feels unusual in their filmography. In fact, it encapsulates so much of the directors' interests, methods, and collaborators that few of their films feel more like a Coen brothers movie than "The Big Lebowski." It was all hiding in plain sight for the folks back in 1998. Just nobody was ready to see it yet.

A deep love of genre

The Coen brothers are deeply indebted to the classic storytelling traditions of 20th-century American cinema and literature. They especially love the hard-boiled crime works of the century's early decades. Starting with their neo-noir debut "Blood Simple," the twisty plotting and hard-bitten characters of the genre were firmly established and only continued on from there. Nearly every film they make involves some sort of criminal plan that either needs to be solved or shows how it goes sideways for the person committing the crime. Dashiell Hammett, the writer behind "Red Harvest" and "The Thin Man," and Raymond Chandler, writer of "The Big Sleep," are a particular influence on the brothers, and their fingerprints are all over "The Big Lebowski."

Chandler's most famous character is the private detective Philip Marlowe, most famously portrayed by Humphrey Bogart in the film adaptation of "The Big Sleep" by Howard Hawks. For "The Big Lebowski," instead of having a character like Marlowe at its center, they flip the genre on its head by having the ultimate slacker, The Dude, play the part of the private detective. Sure, there are plenty of well-written, expertly executed gags, but so much of the comedic circumstances from which those gags can work simply come from the fact that the Coens completely understand the genre they are maneuvering through. It's not enough that The Dude does funny things. You actually need to care about the mystery he is embroiled in. Otherwise, there's nothing to hang your hat on.

"The Big Lebowski" is also pulling from things like Preston Sturgess comedies and Busby Berkeley musicals as well, adding to the film's unusual texture and steeping it even further into those storytelling traditions.

A fascination with religion

A misconception about the films of the Coen brothers is that they don't care about their characters or actively want to punish them. This is a miscalculation of how they see the world. Importantly, Joel and Ethan Coen are Jewish, and each of them have very strong connections with the stories and themes of the Old Testament, which they frequently explore in their work. If you go back and actually read those stories, they are cautionary tales of the consequences of the foibles of man. The Coens often make films about a character who makes a poor, self-interested decision, and the rest of the film chronicles the fallout of that decision.

Their interest in religion isn't just in storytelling terms, though. It is also discussed explicitly with characters. Be it the semi-autobiographical 1960s Jewish community in "A Serious Man" or the council of religious leaders in "Hail, Caesar!," the Coens often feature characters who belong to a faith group and examine the funny, sometimes contradictory ways their faith interacts with their personality. In "The Big Lebowski," we see this in John Goodman's Walter Sobchak.

Walter converted to Judaism when he got married. Even though he is now divorced, he still practices Judaism and militantly shomer Shabbos, which is someone who only uses the day of the Sabbath as a day of rest, prayer, and ritual. When he isn't observing the Sabbath, Walter is a firebrand, quick to yell and scream and berate at a moment's notice, but his anger is typically directed at those who break rules, something a practicing Jew shouldn't do. In his mind, everything he does is righteous and explainable, even threatening someone with a gun. The Coens are fascinated by the lives of religious people, even more so when they don't act like it.

The Coen brothers' stock company

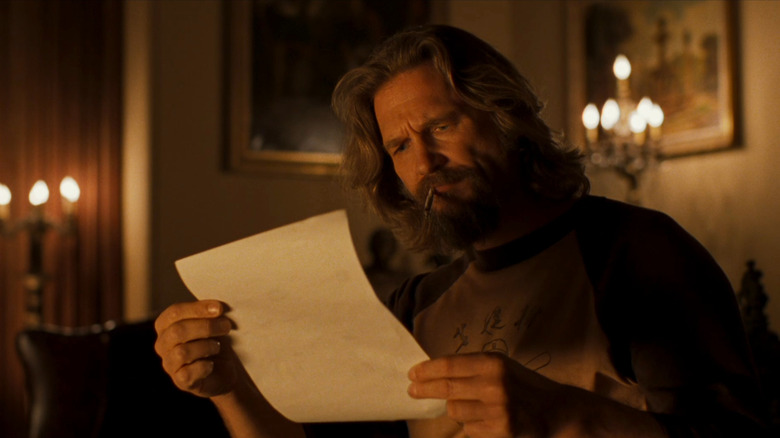

Over the course of their career, the Coen brothers have racked up a ton of people both in front of and behind the camera that they bring from project to project. Even though "The Big Lebowski" was seen as a departure for the brothers, nearly everyone involved is still part of their usual company. On screen, you have John Goodman, Steve Buscemi, John Turturro, Peter Stormare, and, in a very small role, Jon Polito, all returning from previous projects. The only major Coen collaborator from that era you are missing is Frances McDormand. Our lead is Jeff Bridges, working with the Coens for the very first time, but he would go on to reunite with them in 2010's "True Grit." They love to collect idiosyncratic character actors and mix and match them in all of their projects because these films require such a specific fidelity to language and the ability to nail a tricky tone. Once they find these actors, they don't let them go. You can always tell when another filmmaker is really trying to do what the Coens do because they will often cast one of their stock players in a movie (I'm looking at you, Michael Bay).

Behind the scenes, you have all of the usual suspects as well, including cinematographer Roger Deakins, composer Carter Burwell, editor Tricia Cooke (who is also married to Ethan Coen), costume designer Mary Zophres, storyboard artist J. Todd Anderson, and more. Production designer Rick Heinrichs didn't go on to work with the Coens after this movie, but he did work on "Fargo" previously. They have amassed a group of talented craftspeople who know exactly how they like to work and how to get their vision onto celluloid. Though the actors are the flashier stock company, that company is just as strong behind the camera.

Utterly bizarre one-scene characters

No one in a Coen brothers movie is ever just a functionary. When a character steps on screen, you can imagine an entire life for them, and none of those lives are ever boring. My favorite example of this is the Bear Man in "True Grit." Whenever someone like him shows up in one of their movies, all you want is an entire film delving into the life of that person. In the case of "The Big Lebowski," that actually did happen a number of years later when John Turturro wrote and directed a spin-off based on his character called "The Jesus Rolls." But I'm talking about the really small, ultimately inconsequential characters.

A perfect example of this is David Thewlis as Knox Harrington. In terms of story, there is literally no reason for this character to exist. All he does is sit in the art studio of Maude Lebowski (Julianne Moore), reading a magazine and laughing like a hyena. Even The Dude is just standing there completely bewildered by who this guy is and why he's there. Once the scene ends, he never shows back up and is never mentioned. The Coens are brilliant at creating these characters that are only meant to flesh out the world they've created and provide a connection to these people's lives off-screen.

"The Big Lebowski" is littered with these characters. You have the incredibly aggressive Malibu police chief, porn magnate Jackie Treehorn (Ben Gazzara), who draws cartoon men with giant erections for no reason, The Dude's meek, interpretive dancing landlord, and the iron lung-bound former television writer and his silent, stubborn son. Even the cop who recovers The Dude's stolen car makes an odd impression.

The Coens always switch things up

In thinking about auteurs, people are quick to put filmmakers in a box. Just look at the number of people who think Martin Scorsese only has made gangster movies over the course of his career. Of course, this couldn't be further from the truth, but in examining a filmmaker, it makes things easy on the examiner if every film a person makes resembles the last one. It makes charting progression or regression simpler. Joel and Ethan Coen will always zig when you want them to zag.

After making their down-and-dirty neo-noir "Blood Simple," what did they do? They made the cartoonish comedy "Raising Arizona." After that, the period mob drama "Miller's Crossing." Whenever they make a movie, you can guarantee that the follow-up is going to be nothing like the previous film. People should have seen this coming with "The Big Lebowski." Just because "Fargo" put them on a new strata of recognition didn't mean Joel and Ethan Coen were going to change how they operate. Why would they? Creativity is never born out of staleness. You constantly have to be trying new things if you want to fulfill yourself as an artist. It's funny how a decade later, the same exact thing happened when they made the goofy political comedy "Burn After Reading" after the Best Picture-winning dark Western noir "No Country for Old Men."

Because "The Big Lebowski" is something you wouldn't expect from the Coen brothers, that is why it is exactly what you should expect from the Coen brothers, and once you are able to reconcile your whiplash, you will quickly see how everything that makes them the singular, brilliant filmmakers they are is plainly present in "The Big Lebowski." 25 years later, it's certainly obvious.