Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull Is The Anti-Rocky

When "Rocky" hit theaters in 1976, a good portion of the public was enthralled by the sport of boxing. Though some were repulsed by the violent spectacle of two human beings pounding the tar out of each other with eight-ounce gloves, heavyweight title fights drew huge television ratings worldwide, thanks in large part to the prominence of master self-promoter Muhammad Ali. His return to the sport, after being suspended for refusing to serve in the Vietnam War on religious grounds, resulted in a trilogy of unforgettable bouts with Joe Frazier and a rope-a-dope masterpiece against George Foreman. These fights were inspirational displays of intestinal fortitude fueled by searing emotional stakes. To lose the world heavyweight title on a global stage was to suffer a grievous blow to one's pride. Throwing in the towel was unthinkable. The only way Ali, Frazier or Foreman could allow themselves to lose was by knockout or decision. These fights were brutal.

Sylvester Stallone savvily capitalized on this excitement with "Rocky" by imagining a once-in-a-lifetime title bout between an Ali-like superstar and a down-and-out Philadelphia club fighter. As directed by John G. Avildsen, the film is suffused with New Hollywood grit, but it's pure Hollywood hokum at its core. Though the palooka protagonist runs with a rough crowd, the most frightening figure in the film is also its most pathetic: Paulie (Burt Young), Rocky's best friend who takes his booze-soaked frustrations out on his mousy sister (Talia Shire). Everyone in this movie — even, seemingly, the local loan shark who employs Rocky as the world's gentlest enforcer — is kind. Rocky's gruff trainer, Mickey, rides the fighter hard, but when Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers) sends a battered Balboa to the canvas in the 14th round, he begs his gladiator to stay down for his own physical well-being.

"Rocky" is basically an advertisement for boxing. It celebrates the kind of bravery evinced by Ali and his contemporaries, while coaxing an underdog, nose-to-the-grindstone dream out of the viewer. It's "The Champ" with a happy ending. But while it captures the fistic ferocity of boxing, it is a fantasy. It's critical and commercial success demanded a realistic corrective, and it was delivered with rib-cracking viciousness by the filmmaker whose masterpiece lost Best Picture to "Rocky" in 1976.

Scorsese's penance and salvation

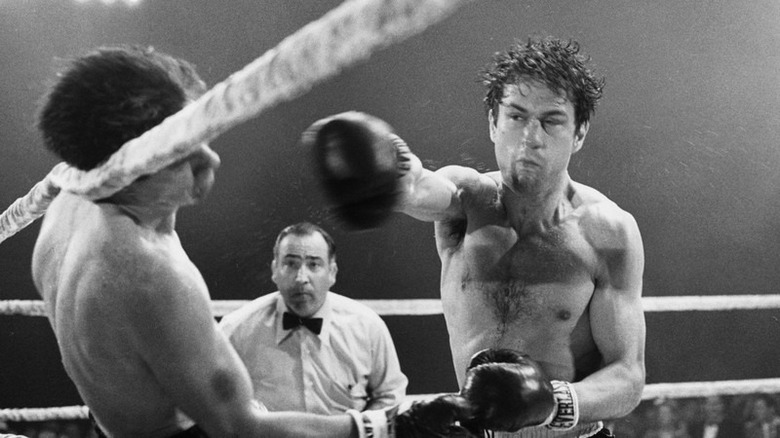

Martin Scorsese was still reeling from the 1977 fiasco of "New York, New York" when he came to "Raging Bull." He self-medicated with cocaine, and was hospitalized with internal bleeding when Robert De Niro threw him a lifeline: let's make a biopic about one of the most self-destructively savage boxers to ever set foot in the ring. The asthmatic Scorsese, who'd subjected his body to a narcotic pummeling, accepted his friend's offer, and hurled himself into the project.

There's a touch of an underdog tale in the making of "Raging Bull." Scorsese, who believed his career was finished, kicked his addiction and roused himself to compose a symphony of abuse. The film, however, is the antithesis of this journey, and the rabbit-punching counterpart to "Rocky." Middleweight great Jake LaMotta, aka "The Bronx Bull," was a feared and loathed fighter driven by a sociopathic desire for punishment. LaMotta was uniquely terrifying in that he lacked knockout power. You didn't beat Lamotta, you survived him. If he put you down, it was because he got inside and turned you into a human heavy bag. He lived life the same way, doggedly abusing friends and family, daring them to absorb blow after blow — emotionally and physically — for the pleasure of remaining in his orbit.

A ferociously unlikable hero

After a transfixing, slo-mo opening credits sequence scored to the Intermezzo from Pietro Mascagni's "Cavalleria Rusticana," where LaMotta bounces balletically about in the ring as flashbulbs pop in a smoke-filled arena, Scorsese plunges us into the bitter chaos of the boxer's life. He's just lost his first professional fight, and, despite this, his brother Joey (Joe Pesci) is scrambling to use his mafia connections to land LaMotta a middleweight title bout. LaMotta wants no part of this. As for the 15-year-old Vickie he's encountered at a Bronx swimming pool, he wants every part of that — even though he's married and considerably older than her. In between these episodes, LaMotta goads Joey into punching him repeatedly in the face for no particularly good reason.

To recap, less than a half-hour into the movie, Scorsese has established that our protagonist is a mob-connected, masochistic boxer who chases teenagers. We're a long, long way from "Rocky."

Working from a script credited to Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin, Scorsese actively discourages his audience from rooting for LaMotta. His narrative arc isn't about wins and losses, it's about giving as good as he gets. The punishment is the point. Staying vertical while getting dismantled by Sugar Ray Robinson (Johnny Barnes) is the flipside to Rocky's earnest longing to go the distance with Creed. LaMotta doesn't care what the world thinks of him; he wants to hurt and bleed and live to taunt his opponent for not knocking him down.

The awful truth about boxing... and ourselves

Rocky Balboa and Jake LaMotta represent extremes in the world of boxing, and the latter is far more representative than the former. No one who excels at boxing is a saint. The sport is the acme of personal achievement and failure. You alone bear the responsibility for your success or failure, which means you must harbor the dark urge to tenderize another person's face into hamburger. The worst we see from Rocky in the first film is his association with the loan shark (for whom he can't break so much as a finger). He's a punch-drunk prince of a man. It's lovely, and it makes us feel great about ourselves and the world around us, but it isn't boxing.

As portrayed by Scorsese and De Niro, LaMotta is the primal apotheosis of boxing. There's nothing sweet about his science. He's in it for the pain. The outcome doesn't matter. They say that fighters are motivated by fear in the ring. As Sugar Ray Leonard told me in 2011, it's less the fear of losing than the fear of dying. LaMotta, however, doesn't know fear. He doesn't care if he lives or dies. He was placed on this earth to do violence, and that violence is in all of us. It's base and it's upsetting, but the purpose of throwing a punch is to inflict damage on your fellow human being. That's boxing. And the fact that I'm a fan places me much closer on the spectrum of decency to LaMotta than Balboa.