Eddie Murphy Is The Best Actor Ever

(Welcome to Best Actor Ever, an ongoing series where we explore the careers and performances of the greatest performers to ever grace the screen.)

We're only six articles into this series, and I've already violated my critic's creed by furthering one of the most egregious filmmaking fallacies in existence. While I stand wholeheartedly behind my selections of Meryl Streep, Denzel Washington, Cate Blanchett, Robert De Niro, and Viola Davis, these artists are venerated for capital-A acting. They play serious, complicated people beset by demons both personal and societal. Critics expect them to dazzle us, to shed inspiring or unsettling light on the human condition. For too many years, they did not expect them to make us laugh.

When Streep, after a decade-plus of electrifying dramatic performances, appeared in the 1989 dark comedy "She-Devil" opposite TV superstar Roseanne Barr, many critics felt she was slumming. Ditto De Niro in Martin Brest's 1988 buddy-comedy "Midnight Run." Though it's rightfully considered an action-comedy classic nowadays, some fretted that the man renowned for deep-tissue character studies had wasted his formidable talents on what Newsweek's David Ansen derided as "an unworthy cause."

This idiotic notion that comedy is somehow an "unworthy" cinematic pursuit has been backed up by major awards organizations, with the Academy Awards being particularly allergic to the genre. There are exceptions (most notably Frank Capra's 1934 screwball masterpiece "It Happened One Night," which is, to date, one of only three movies to sweep the major Oscar categories of Picture, Actor, Actress, Director, and Screenplay), but aside from happy surprises like Kevin Kline's Best Supporting Actor win for "A Fish Called Wanda" and Marisa Tomei's righteous Best Supporting Actress victory for "My Cousin Vinny," comedy remains "unworthy" in the eyes of critics and awards voters.

This is infuriating because if comedy were properly valued, Eddie Murphy would be considered the Laurence Olivier of laughter.

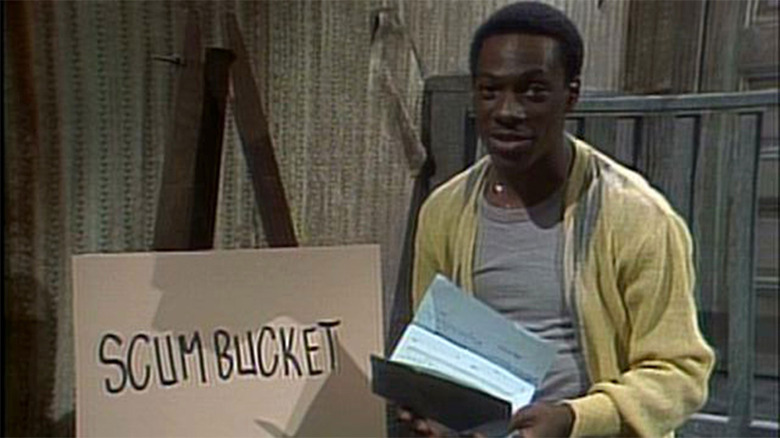

The saint of Studio 8H

Edward Regan Murphy was 19 years old when he saved "Saturday Night Live."

As the hugely popular sketch series approached its sixth season in 1980, producer Jean Doumanian had taken the series' reins from a burned-out Lorne Michaels. Faced with the unenviable task of replacing the original Not Ready for Prime Time Players, she botched just about every hire. Charles Rocket, who was hyped as the next Chevy Chase, was screamingly awful before he got bounced for saying the f-word on the air. Denny Dillon, Gail Matthius, and the late, great Gilbert Gottfried were talented, but ill-suited to sketch comedy. By the end of the season's second episode, a ghastly wipeout hosted by Malcolm McDowell, the show was on NBC's chopping block.

Worst of all, the live studio audience was dead. Viewers accustomed to roaring laughter at the brilliant antics of Gilda Radner, Dan Aykroyd, and Bill Murray were treated to forced titters from people who'd rather be anywhere else than Studio 8H. Robert Schuller was getting bigger laughs on Sunday morning. Then, unknown featured player Murphy joined Joe Piscopo on episode three's Weekend Update as aggrieved high-school basketball player Raheem Abdul Muhammad, and the damndest thing happened: the audience was howling.

The show's turnaround was swift. Murphy was bumped up to the repertory cast in early 1981 and brought the house down via his first "Mr. Robinson's Neighborhood" skit on, ironically, the same episode Rocket earned his walking papers. Chevy Chase hosted the final episode of the season, and, flanked by Robin Williams and Christopher Reeve, begged viewers to stick with the show. It was a needlessly desperate move. No one wanted to hear from Chase. They wanted to see Eddie.

Eddie and Elvis

Murphy's meteoric rise to superstardom as a solo performer in the television age has one precedent: Elvis Presley. But whereas Presley's appeal was musical and scandalously below the belt, Murphy connected as a comedic dynamo. He was explosively funny, and that was it. When he stepped in front of the camera, people were primed to laugh, not orgasm. Was he de-sexed by a white entertainment establishment in a post-Blaxploitation world that shunted the wildly desirable Billy Dee Williams to Colt .45 commercials? Possibly. But the rules were different for comedians, especially those of color. Murphy was a good-looking kid, sure, but no one was trying to get with Mr. Robinson, Gumby, or Buckwheat.

Murphy understood this, so the boundlessly talented performer, who was doing all of the heavy lifting for "SNL" and new producer Dick Ebersol, did the most Elvis thing he could: he used his 1982 hiatus from the show to become a movie star as convict Reggie Hammond in Walter Hill's "48 Hrs."

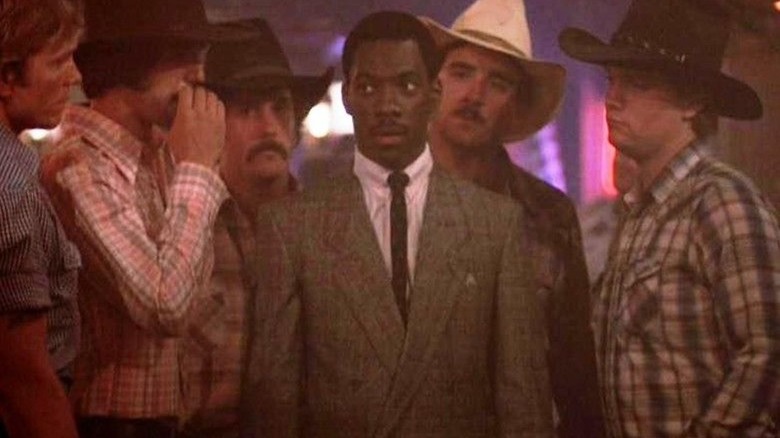

When Roger Ebert opined in his 1982 review of "48 Hrs.," "Sometimes an actor becomes a star in one scene," he compared Murphy's blazingly funny shakedown of a redneck bar to Jack Nicholson donning a football helmet in "Easy Rider" and Faye Dunaway's sensuous gaze from her bedroom window in "Bonnie and Clyde." While he was right in a sense, that we fell hard for these actors in these moments, they are just moments. Murphy rousting a bar full of rednecks is a meal. Also, it's technically not a star-making scene because Murphy was red-hot coming off his second season of "SNL." Movie theaters weren't packed on opening night with "Rich Man, Poor Man" fans. They wanted to see Eddie. And they got him raw and uncut.

Telling off bigots

The Torchy's scene has only acquired more power over the years due to the renewed vigor of racists in the public square. Prior to entering the establishment, Murphy tells Nolte's bigoted cop, Jack Cates, who believes the mouthy Hammond lacks the "bulls*** and experience" it takes to intimidate a bar full of hicks, to "Come in and experience some of my bulls***." Hammond takes charge immediately by downing a shot of vodka, hurling the glass through the bar mirror, and grabbing the bartender roughly by his shirt collar to demand information.

The 5'9" Murphy had just turned 21 when he shot this scene, but he reads as a grown man on screen. And while Hammond might be impersonating a cop, he isn't bullsh***ing. The experience is being Black in America, and this spikes the bulls*** with an exquisitely controlled fury. "I don't like white people. I hate rednecks. You people are rednecks. That means I'm enjoying this s***." Then he drops the hammer when one of the patrons challenges him. "You know what I am? I'm your worst f***in' nightmare, man. I'm a n****r with a badge, which means I got permission to kick your f***in' ass whenever I feel like it!"

That last line could hit a little more awkwardly given the recently revealed murderous exploits of the Memphis Police Department's Scorpion Unit, but in context, it's a haymaker, and Murphy lands it flush. This exchange is sharply contrasted by Hammond's relationship with Cates, who taunts him with racist invective until they get into a fight. The scrawny, 21-year-old Murphy holds his own verbally and, remarkably, physically with the burly Nolte. You never question the mismatch because anyone with Hammond's mouth only survived his childhood because he could back up his talk with his fists. Off-camera, Murphy didn't look the part. On camera, he was lethal, quick-witted perfection. He didn't disappear like Meryl Streep or Daniel Day-Lewis are known to do; he made minor adjustments to his smartass persona, and gave us a wily, con-artist performance on par with Paul Newman in "The Sting" or Barbara Stanwyck in "The Lady Eve."

The backlash and the disrespect

Murphy's shockingly sudden stardom compelled him to quit "SNL" before the end of its ninth season, which, along with his shoehorned-in appearance in Paramount's Dudley Moore flop "Best Defense," primed the pump for a backlash. Though he was a riot in John Landis' masterful "Trading Places" opposite Dan Aykroyd, critics vaguely expected something better, something they couldn't articulate. They believed he was wasted in Martin Brest's blockbuster action-comedy "Beverly Hills Cop," but what did they want Murphy to do? He was a Black superstar in Hollywood and his biggest hit was a formulaic crowd-pleaser that had been developed for Sylvester Stallone, but the rewrite retained the character's white friends! Murphy, who'd signed a multi-picture deal with Paramount and saw how shoddily the studios had treated his idol Richard Pryor, opted to play the game. He made "The Golden Child," "Beverly Hills Cop II" and the stand-up film "Eddie Murphy: Raw."

Murphy was at the peak of his box-office powers in 1988 when he re-teamed with Landis to make the fish-out-of-water romantic comedy "Coming to America." It's a lovely celebration of Black culture that provided Murphy and co-star Arsenio Hall the opportunity to portray multiple characters via Rick Baker's makeup wizardry. Peter Sellers earned an Academy Award nomination for pulling off this feat in Stanley Kubrick's "Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb," but Murphy's achievement was brushed aside as a goofy stunt — even though there were gasps in theaters across the country when the curtain-call end credits revealed he'd played an elderly Jewish man.

The next eight years would be rough for Murphy. He was terrific in Reggie Hudlin's "Boomerang," but barely showed up for "Beverly Hills Cop III" and "The Distinguished Gentleman." Most disappointingly, he phoned in his second go-round of Reggie Hammond in "Another 48 Hrs." Murphy seemed bored and in danger of proving his critics right, that he cared more about paychecks than challenging himself as an actor.

He showed these fools up in 1996.

The many faces of Eddie Murphy

Wes Craven's "Vampire in Brooklyn" was a strange departure for Murphy, one that indulged his love of horror and makeup-enhanced, multi-character antics. Tonally, the comedy overpowers the terror, especially when Murphy's protagonist takes on the guise of a pompous preacher and convinces his congregation to chant "evil is good." Fortunately, this failure did not deter Murphy from pursuing his Sellers-esque passion.

No one was clamoring for a remake of Jerry Lewis' "The Nutty Professor" in '96. It was a relic of the early '60s that held no appeal for Gen-X moviegoers, a dated takedown of hipster fraudulence. Murphy, however, had a humanistic variation in mind.

Whereas Lewis played two wildly exaggerated characters in the uber-nerdy Professor Kelp and the obnoxious ladykiller Buddy Love, Murphy buried himself under layers of latex and turned his protagonist, Sherman Klump, into a kindly chemist with body-image issues. When he tests his own weight-loss serum on himself, he turns into an abrasive, svelte horndog who objectifies women. He is Klump's Hyde, the inverse of everything that makes him outwardly loveable and inwardly sad.

Dying is easy, comedy is hard

There are two bravura sequences in "The Nutty Professor" where Murphy plays every member of his family save for his young nephew, and he probably sacrificed his shot at an Oscar nomination by concluding both scenes with a cascade of farts. But each of those characters — his doting mother, his blustery father, his untoward brother, and his oblivious grandmother — are facets of Sherman's personality. Amid the broadness of the comedy, Murphy particularizes, and he leaves us feeling for Sherman, who feels he is unworthy of love due to his size. Sellers never liked his characters this much.

Murphy nearly won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar in 2006 for his dramatic portrayal of a heroin-addicted R&B singer in Bill Condon's "Dreamgirls," but, in a cruel irony, he was bested by Alan Arkin's phoned-in take on the dirty-old-man stereotype in the execrable "Little Miss Sunshine." Every critic who slammed Murphy for making formulaic comedies in the 1980s owes him an apology. He chose to set his own standard rather than be judged by a bogus, prestige-obsessed hierarchy. And when he played their game, they shunned him.

Most serious actors don't touch comedy because they're not good enough to do it. Eddie Murphy could slay as Freddie Mercury, but Rami Malek could never touch "The Nutty Professor." And that's some bulls*** I'm tired of experiencing.