Who Framed Roger Rabbit Set The Stage For Disney's Success With The Little Mermaid

"The Little Mermaid" saved Walt Disney Feature Animation in 1989. It earned rave reviews from critics like Roger Ebert, who wrote that "the magic of animation has been restored to us." It won an Academy Award and a Grammy for the hit song "Under the Sea." Best of all, the film popularized animated musicals; not just animated films with songs, but films with songs that expressed motivation and character as aptly as the animation did. Lyricist Howard Ashman and composer Alan Menken, responsible for the off-Broadway legend "Little Shop of Horrors," brought their hard-won expertise to a project that was floundering on the rocks. The results didn't just set the standard for the Disney Renaissance; they set the standard for its competition. For the first time in many years, Disney took the lead as opposed to ceding ground to challengers like Don Bluth. Not every film in the coming years would be successful, but they carried themselves with confidence and ambition, qualities that had long evaded Disney's crew of animators following the death of the studio's founder.

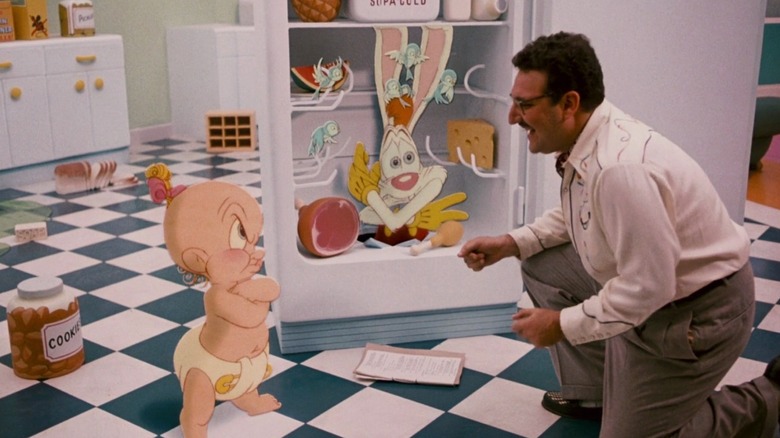

"The Little Mermaid" was not Disney's first great animated film of the 1980s. That honor belongs to "Who Framed Roger Rabbit," an animated live-action hybrid released via Disney's Touchstone Pictures studio in 1988. "Roger Rabbit" broke every rule in the book. It was a Los Angeles-based film noir filmed in the United Kingdom, starring cartoon characters that could be funny, sexy, or scary, scene by scene. The film delighted some children, scarred others, and left a few with a distinct fondness for weasels later in life. By no means could it be squared with the sincere, prestigious Disney Renaissance. Yet without "Roger Rabbit," the Disney Renaissance might have never happened.

Illustrated radio

By the 1980s, many in the United States no longer took animation seriously. Animated shorts moved from theaters to television, where they were made to adhere to stricter schedules and content guidelines. Animated characters now expressed themselves through dialogue rather than movement. "Looney Tunes" animator Chuck Jones blasted these series as "illustrated radio," claiming that even entertaining dialogue (such as in "The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle") could not salvage poor animation. Meanwhile, the deregulation of the animation industry by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s led to an explosion of cartoons meant to sell children's toys. Cartoons like "He-Man and the Masters of the Universe" were entertaining enough for kids and gave future luminaries like Bruce Timm valuable experience. But they had little to offer folks who weren't buying what they were selling.

Of course, plenty of fascinating animation was still being made. Don Bluth's films made in collaboration with Steven Spielberg, including "An American Tail" and "The Land Before Time," proved that animated films could be successful outside of the Disney umbrella. Ralph Bakshi's "Fritz the Cat" did the same for adult-oriented animation. Meanwhile, in Japan, anime grew as a cultural force throughout the '70s and '80s as shows like "Mobile Suit Gundam," "Heidi, Girl of the Alps," and "Rose of Versailles" broke ground at home and abroad. Some of them, like "Space Battleship Yamato" and "Super Dimension Force Macross," even found success on U.S. television as "Star Blazers" and "Robotech," respectively.

Hollywood in England

"Who Framed Roger Rabbit" always had one foot in animation abroad despite its Disney origins. Its animation director, Richard Williams, was a Canadian that worked in London and wrote the definitive animation textbook in 2001. Williams requested that "Roger Rabbit" be made on his turf, so Disney created Disney Animation U.K. as a home for the production. Cinematographer Dean Cundey said in American Cinematographer, "we had to recreate Hollywood in England, even bringing in palm trees from Spain." While some scenes were filmed in Los Angeles, "the United States was actually a distant location for us." This suited "Roger Rabbit" just fine. The film wore its love for the glory days of U.S. animation on its sleeve, paying homage to characters that (per screenwriter Jeffrey Price) had long languished in the hands of clueless producers. But the cast and crew were just as dedicated to playing up the hilarious, spooky weirdness that came with animated characters inhabiting the real world.

Mixing animation and live action was a tricky business. Disney passed along tips and tricks they learned through 1977's "Pete's Dragon" to the crew of "Roger Rabbit." According to Cundey in Gizmodo's oral history, these included keeping the camera steady, lighting the set evenly, and avoiding light and shadow. Cundey and his team proceeded to break these rules immediately. "The great boon of the picture is that we didn't adapt our technique to an easier, more conventional way," he told American Cinematographer. This meant panning and tilting the camera when necessary, varying the lighting, and doing "everything exactly as if the cartoon characters were alive ..." This resulted in a far more expensive, time-consuming production. But every minute and penny could be seen on screen.

Pulling a rabbit out of a hat

"Roger Rabbit" is not a seamless production, but it doesn't matter. The film is so ambitious and convincing that its seams impart personality instead of failure. This is a movie where animated weasels hold real-life guns. A movie where a cartoon rabbit drinks water and spits it out. The crew didn't just invent the techniques and technology required to produce these scenes, but nailed them on their first try. Even the actors, especially the lead Bob Hoskins, have actual chemistry and rapport with the cartoon characters despite doing their work alongside big rubber objects. George Lucas's "Star Wars" prequels wished they had the charisma of "Roger Rabbit."

The film broke ground in other ways than its technical accomplishments. "Roger Rabbit" parodies the noir femme fatale with the buxom Jessica Rabbit, but allows her a smidgeon more grace than I expected going in. It showers its cartoon cast with love and affection, but then depicts their home of Toontown so bizarrely that the viewer understands just why Bob Hoskins hates it there. The film even works in a dig at Los Angeles's highways, which per Gizmodo forced the closure of the city's beloved mass transit system in 1961. The question of car dependency is just as relevant today, with rapid climate change demanding solutions to lower carbon dioxide output. Earlier Disney films told simple, accessible stories with elemental power. "Roger Rabbit" proved that a Disney film could hold many contradictions, and still be a smash hit.

I always chose real

Folks at Disney suspected that "Roger Rabbit" could benefit the studio's animation as a whole. According to ARTpublika Magazine, studio executive Jeffrey Katzenberg "argued that the hybrid of live-action and animation would 'save' Disney's animation department." Let it be said that Katzenberg was a hack with no prior experience in animation, who argued against the inclusion of the character-defining song "Part of Your World" in "The Little Mermaid." In this one instance, though, Katzenberg was correct. "Roger Rabbit" reminded audiences that great works of the past existed, and that new animation could be great in its own right.

Animation didn't have to be low-rent children's programming on television. It could be funny, scary, or sweet. It could be anything. It was perfect timing for the creators of "The Little Mermaid," who sought to prove with their film that Walt Disney Feature Animation was a force to be reckoned with. Co-director Ron Clements said to IGN that "a whole new generation of animators" were "feeling like 'this is a film we can really...prove ourselves on.'" Among them was Glen Keane, who animated Ariel in "The Little Mermaid." Keane drew Ariel as a teenage girl grappling with relatable feelings and desires, instead of a smiling fairy tale character. "Anytime I had the choice to go pretty or real," Keane told Variety, "I always chose real..." Just like "Roger Rabbit" had brought animation to live action, the new Disney crew imbued their fairy tale worlds with realism.

More than appreciation

"The Little Mermaid" was followed by "Beauty and the Beast" in 1991, which was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar the following year. From that point forward, Walt Disney Feature Animation was the studio to beat in the United States for animated film. Elsewhere, though, animation was picking up steam. The influential anime blockbuster "Akira" was released in the United States at the end of 1989, introducing the country to the power of Japanese animation. Just one year earlier, Hayao Miyazaki's "My Neighbor Totoro" screened in Japan, becoming Studio Ghibli's first real financial success. On TV, Amblin Television leveraged the success of "Roger Rabbit" to produce bizarre cartoon comedies like "Tiny Toon Adventures" and "Animaniacs." They followed in the footsteps of Disney's own "DuckTales," which set the bar for TV animation on its release in 1987.

For many years, the craft of animation had languished in the United States. Now it was on the move again, with "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" standing at the crux of this reawakening, bridging the past and the future of the medium. Roger Ebert would say of "Roger Rabbit" that "what you feel when you see a movie like this is more than appreciation. It's gratitude." I feel the same way.