The Dark True Story Behind Vincent Price's Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins

I grew up in Suffolk, UK, one of the old stamping grounds of Matthew Hopkins, the nefarious witch-hunter whose zealotry would one day be captured on screen by Vincent Price in the 1968 horror movie "Witchfinder General." As a fan of legends and lore, I once researched a piece on local witchcraft for my A-Levels, spending many an afternoon in the Suffolk Records Office. It was a delightfully eerie experience, sitting in a darkened room peering down the lens of a microfilm viewer at 300-year-old accounts of bewitchment, familiars, and curses.

One story still sticks in my mind. A witch took a dislike to a man in her village and sent an army of spiders to torment him. Eyewitnesses supposedly saw hundreds of the things swarming his house and weaving their webs. His frightened neighbors responded by burning the place down.

The thing that struck me most about these stories was the total credulity of the authors. There was rarely a sense that they ever queried the veracity of the tale, no matter how bizarre. This was a sign of the times, however, because everyday folk in the 17th century were deeply superstitious. Per Tudor Times:

The Kingdom of Darkness was as real to them as the Kingdom of Heaven, and ordinary people everywhere believed in devils, imps, fairies, goblins, and ghosts, as well as legendary creatures such as vampires, werewolves, and unicorns. Everyone feared evil portents, such as a hare crossing one's path or a picture falling from the wall.

Such an atmosphere of fear and superstition made rich pickings for Hopkins, who made a lucrative trade persecuting people accused of witchcraft. He became the subject of "Witchfinder General," a bleak period piece that is now one of the "Unholy Trinity" of folk horror alongside "The Blood on Satan's Claw" and "The Wicker Man." Let's take a look at real Hopkins and his place in the terrible history of witch-hunting.

So what happens in Witchfinder General again?

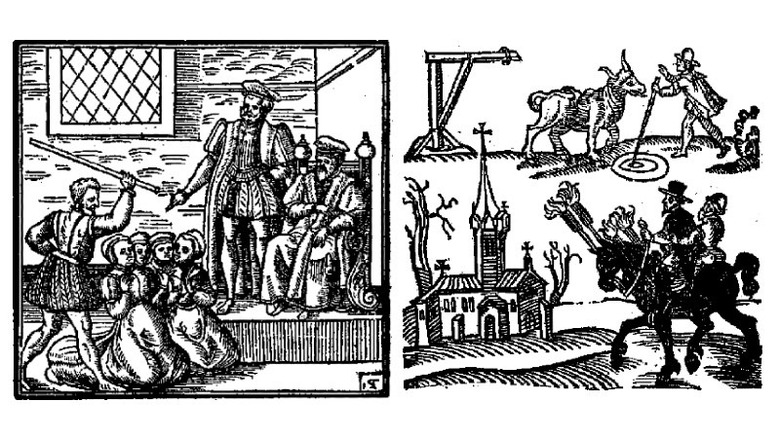

Like the other folk horror films of the Unholy Trinity, "Witchfinder General" sets scenes of horrific violence against a pastoral backdrop. In the opening scene, a man builds a gallows in an open field ready for a condemned witch as Vincent Price's Matthew Hopkins and his sadistic assistant John Steame (Robert Russell) look on. It is 1645, and the lawlessness of Civil War England provides ample opportunity for men like them to make good money witch-hunting. As the poor woman hangs, they head to their next payday in the small Suffolk village of Brandeston.

Young Roundhead soldier Richard Marshall (Ian Ogilvy) returns home to the village on leave to ask permission from the priest, John Lowes (Rupert Davies), to marry his niece Sara (Hilary Dwyer). The old man gives his consent, making Marshall promise he will take her somewhere safe as they have become outcasts in the community. Marshall happily agrees and rejoins his regiment.

In the meantime, Hopkins and Steame arrive in the village to investigate Lowes, who is accused of idolatry and witchcraft. They try to force a confession from him through torture, and Sara tries to save him by offering herself to Hopkins. She only manages to buy her uncle a brief reprieve in prison, however, as Hopkins changes his mind after Steame sexually assaults her. Lowes is hanged along with two women.

Marshall returns to Brandeston and vows revenge, setting him on a hellbent path that turns the upstanding young soldier into a vindictive man just as violent as his enemies. "Witchfinder General" is a stark and unsettling tale of corruption, greed, and abuse of authority; unlike its fictional counterparts in the Unholy Trinity, it derives its disturbing power from being based on real events.

The start of Britain's deadly witch-hunting craze

In September 1589, King James VI of Scotland set out across the North Sea to pick up his bride-to-be, Ann of Denmark, but his fleet was beset by a terrible storm and he was forced back. When he finally made it across calmer waters to marry Ann in Oslo, he heard superstitious rumors that the tempest was a witchcraft-fueled plot to kill him. Those tales inspired the King to undertake his own reign of terror in Scotland and England, starting with the people he suspected of bewitching his voyage.

He became obsessed with witchcraft and in 1597, he published "Daemonologie," a philosophical tract on witchcraft and necromancy that proved influential across Europe. When he took the English throne in 1603 to become King James I, he passed a Witchcraft Act in Parliament the following year. The statute introduced the severest punishment for acts of witchcraft, as demonstrated by the Pendle Trials of 1612 which resulted in ten members of the same family being hanged.

Witch hunts were especially deadly for women. Over 95% of people convicted as witches were female, and poor women who lived alone with animals, often outsiders, were the most vulnerable. No one was completely safe: Just one accusation was enough for a person to face trial and a huge majority of those accused were found guilty.

James's passion for witch-hunting waned in the years before his death in 1625, with a corresponding lull in activity around Britain. Fear and persecution of so-called witches returned again with a vengeance during the English Civil War (1642-1651) when the most infamous witch-hunter of them all made a very dubious name for himself.

The real Matthew Hopkins

Born in Great Wenham in Suffolk sometime around 1620, Matthew Hopkins was much younger than Vincent Price's screen version. The horror icon was in his mid-50s when he took the role, while the real Hopkins was only in his 20s when he embarked on his witch-hunting spree. Fear of witches was rife in rural areas, and Hopkins took full advantage of the political and religious turmoil that accompanied the English Civil War, targeting communities that were only too willing to pay for his services.

Claiming to have a mandate from Parliament, Hopkins traveled around the counties of East Anglia with his sadistic cronies, torturing confessions from unfortunates accused of witchcraft. His favorite methods of identifying witches included pricking and "swimming." In the pricking test, the accused was poked or stabbed to see if they bled. If they didn't, it proved they were a witch. Since witch-hunting was a well-paid business, weapons with retractable blades were useful for eliminating any costly doubt.

The swimming test involved tying up the person and throwing them into a pond or a river to see if they would float. If they proved buoyant, it was a sign that they were in league with the Devil and execution soon followed. If the person sank they were in the clear, but many drowned before their tormentors could drag them from the water.

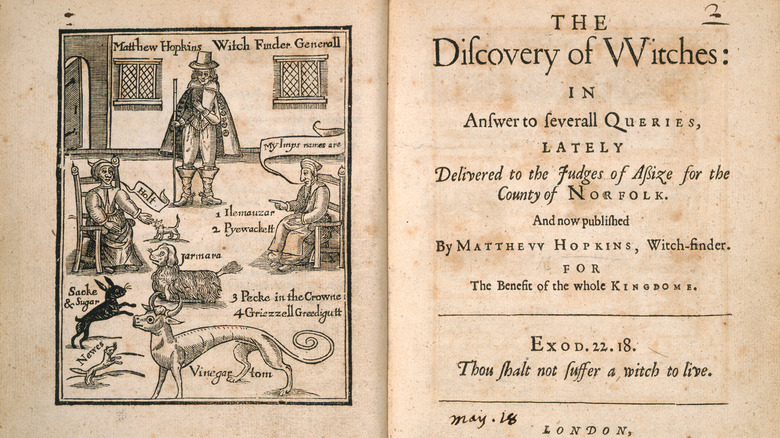

As a former lawyer, Hopkins made his breakthrough into witch-hunting in 1644 in Manningtree, Essex, when he supposedly heard a group of women discussing their meetings with the Devil. 23 were accused and 19 were hanged after the others died in prison. He spent the next three years prosecuting witches and appointed himself Witchfinder General in 1645. His single deadliest shift came in the same year in Bury St Edmunds, when 18 people were hanged in one day.

Witch-hunting made Matthew Hopkins a wealthy man

The witch-hunting activities of Matthew Hopkins made him very wealthy. At a time when a farm laborer was only paid around six pence a day, Hopkins racked up an estimated £1000 for his expertise. The coffer-keepers of Stowmarket paid him £23 for his services and my home town of Ipswich had to introduce a special tax to help cover the costs.

While women suffered the most from Hopkins' methods, men were not immune. One notable example was John Lowes of Brandeston, who provided the name of the priest in "Witchfinder General." Lowes was an elderly vicar who had served the area for around 50 years before falling foul of accusations. After several days of torture, he became "quite weary of his life, and scarce sensible of what he said or did." Before he was hanged he admitted keeping company with two imps, one of which sank a ship off the Suffolk coast on his behalf (per "The Lore of the Land").

Hopkins died in 1647 aged around 27, and persistent legend claims that he had his own methods turned against him when someone accused him of witchcraft. As poetic as that end would be, it is more likely he succumbed to tuberculosis. His three-year campaign of persecution was responsible for the deaths of over 300 people, and shortly before he passed away he published "The Discovery of Witches" detailing his exploits. It is possible that news of Hopkins' work crossed the Atlantic to the colonies in New England, as similar methods were used in witch hunts such as the Salem trials of 1692-93.

Witch-hunts around the world

Systematic witch hunts were far from a solely British phenomenon, dating as far back as the 15th century in Europe. The first documented case began in 1428 in Valais, Switzerland, where 367 people were executed over a period of eight years. While some were beheaded, the usual method was burning by tying the victim to a ladder and dropping them into a fire, something we see in "Witchfinder General."

Over 100 years before King James published "Daemonologie," one of the most famous texts about witchcraft and witch-hunting was published. Inspired by the papal bull of 1484 that condemned the spread of witchcraft in Europe, two supposedly learned men from the universities of Cologne and Salzburg wrote "Malleus Maleficarum," aka "Hammer of Witches," which became the go-to handbook on witchcraft and how to combat it by the 1600s.

The persecution of alleged witches reached its peak in Europe during the 17th century. Germany was a particular hotspot, with an estimated 42 percent of trials resulting in execution taking place in the country. As in Britain, a period of religious and political volatility may have contributed to the rise in superstition and witch-hunting, such as during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). The rise of science and the Enlightenment gradually put an end to the barbaric practice, but it took a long while to fully die out. The last known person executed for witchcraft in Europe was Barbara Zdunk in modern-day Poland as late as 1811. Figures vary, but it is estimated that up to 50,000 people, mostly women, died as a result of witch-hunts during the period 1450-1750.

Witch-hunts on the big screen

When "Witchfinder General" was released in 1968, it joined a wave of similarly-themed films from both Britain and abroad, including Ken Russell's controversial "The Devils," "Witchhammer" from Czechoslovakia, and "Belladonna of Sadness" from Japan. These movies corresponded with a rise in occult interests, stemming from counterculture movements of the '60s that rejected mainstream religion and kicked back against the establishment. As Piers Haggard, director of "The Blood on Satan's Claw," told Mark Gatiss in the TV series "A History of Horror:"

"We were all a bit interested in witchcraft. We were all a bit interested in free love. The rules of the cinema were changing and nudity became possible ... because the lid had slightly been taken off."

Witchcraft and witch-hunts have provided a rich source for films, books, plays, and other works of art. Perhaps because these stories often focus on finger-pointing, paranoia, persecution, and terror, they find relevance in any era; Arthur Miller wrote "The Crucible" in the '50s in response to McCarthyism, while Otakar Vavra's "Witchhammer" was an allegory for the Communist show trials in his country, to give just two examples.

Since the majority of witch-hunt victims were women, tales of witches are always useful when it comes to interrogating toxic masculinity. "The Witch" focuses on a young woman who rejects the oppressive patriarchy of puritanical society and signs up with the Devil. On the stage, Jodie Booth's "Sisterhood," about three women facing trial for witchcraft, performed at several sites connected with Matthew Hopkins during a "healing tour" of East Anglia in 2019.

Over 300 years later, Hopkins and his ilk remain as troubling and relevant as ever. As long as those in positions of authority victimize others for their own ends, they will always be with us.