21st Century Spielberg: Steven Spielberg Goes To Cinematic Therapy With The Fabelmans

(Welcome to 21st Century Spielberg, an ongoing column and podcast that examines the challenging, sometimes misunderstood 21st-century filmography of one of our greatest living filmmakers, Steven Spielberg. In this edition: "The Fabelmans.")

In Susan Lacy's 2017 documentary "Spielberg," Steven Spielberg states: "I've avoided therapy because movies are my therapy." The legendary filmmaker is laughing as he says this, but the comment is telling. In fact, it can pretty much sum up Spielberg's entire career — and personal life.

It can certainly sum up "The Fabelmans," Spielberg's most personal film; the autobiographical story of his childhood that he's been talking about making for years now. Here, Spielberg isn't giving himself a pat on the back and singing his own artistic talents. Instead, he's confronting his own mythology head-on. He's turning the pages of the book backward and investigating what he finds.

Yes, the Spielberg avatar in "The Fabelmans" — young Sammy Fabelman — shows signs of being a great filmmaker. But that's not what "The Fabelmans" is about. It's about Spielberg's own unique form of therapy — the movies — analyzing what goes on in the director's messy mind. As Sammy says late in the film, his thoughts are always chaotic. He even ends up having panic attacks.

It's his work that calms him down. Spielberg, and Sammy, can't control the real world. But they can control the world they create on the screen. More than that, they can shut out the real world that way. As Sammy Fabelman's personal life begins to fall apart, it's his art that keeps him going. Because as much as Sammy loves his family, he loves making movies more. Maybe not much more, maybe just a tiny bit. But more. It's like Spielberg is almost apologizing here for being such a workaholic, and trying to explain why he does what he does.

A lot of courage

"The Fabelmans" started its life as a script penned by Spielberg's sister, Anne. Titled "I'll Be Home," the story was so personal that Spielberg hesitated to bring it to life. In 1999, Spielberg admitted he was afraid of the idea because he worried his parents wouldn't like the film and would "think it's an insult and won't share my loving yet critical point of view about what it was like to grow up with them.”

In a 2002 interview, Spielberg said of the project:

"I'm still nervous about exposing myself so publicly – it's so close to my life and so close to my family – I prefer to make films that are more analogous. But a literal story about my family will take a lot of courage.

And in Richard Schickel's 2012 book "Steven Spielberg: A Retrospective," Spielberg is quoted as saying:

"I've had a story for a long time about my mom and dad that I'm too chicken to make. I'm going to make it someday. But it's hard because I'm taking some deeply personal events of my mom, dad, three sisters, and my life and putting it up there for the whole world to see. I have to go to Oz to ask the wizard for some courage before I make that movie."

As the years went by, Spielberg kept the project in his back pocket. And then the pandemic hit. Spielberg, ever the workaholic, found himself bored and frequently driving around Los Angeles with only his thoughts for company. And Spielberg, being Spielberg, thought about movies he would like to make. On top of that, the filmmaker realized he wasn't getting any younger, and there might be a clock on how many stories he could still tell up on the big screen.

"I started thinking, what's the one story I haven't told that I'd be really mad at myself if I don't?" Spielberg said. "It was always the same answer every time: the story of my formative years growing up between 7 and 18."

Outside looking in

When it came time to finally make this movie, Anne Spielberg's script was out, and Steven Spielberg's script was in — with more than a little help from Tony Kushner. Kushner has joined the ranks of John Williams and Janusz Kamiński as one of Spielberg's greatest collaborators. Kushner seems to "get" Spielberg better than any other writer the filmmaker has worked with over the years, and their collaborations — "Munich," "Lincoln," "West Side Story," and now "The Fabelmans" — rank among some of Spielberg's best movies.

It was surely for the best that Spielberg work with a collaborator on this script rather than tackle the entire thing himself. Otherwise, the filmmaker might've avoided more uncomfortable elements — elements that Kushner surely pushed Spielberg to ultimately explore. It likely helped that the two already had a good working relationship.

"I would not have been able to co-author this film without somebody I truly, dearly admired and adored, and somebody who knew me so well, and whom I so loved and respected, and that happened to be Tony Kushner," Spielberg said. "The only thing that mattered was that I could open up to somebody, unpack all of my suitcases in front of somebody and never feel embarrassed or ashamed."

Spielberg gave Kushner 81 pages of notes that the screenwriter then shaped into an outline. "I had to think through like how to connect these things," the writer said. "With the inimitable depth of familiarity and subjective understanding that Steven brought to this material, it's also good to have somebody who is standing on the outside looking in."

'She was a best friend, not a primary caregiver'

Getting personal isn't new for Spielberg. He's been putting personal touches into all of his films for 50 years now. "Most of my movies have been a reflection of things that happened to me in my formative years," he said. "Everything that a filmmaker puts him or herself into, even if it's somebody else's script, your life is going to come spilling out onto celluloid, whether you like it or not. It just happens."

The divorce of Spielberg's parents can be thought of as a seismic event, not just for Spielberg's personal life, but for nearly his entire filmography. Family, both idealized and prosaic, colors the films Spielberg makes, and his work is littered with absentee fathers and father figures. This arose from a misconception: for years, Spielberg blamed his father, Arnold, solely for his parent's divorce. Like Spielberg, his father was a workaholic, and frequently away from home as a result. In the "Spielberg" documentary, the filmmaker calls his father a "computer genius" who invented the first commercial data processing machine, and adds: "His career demanded a lot of time away from the family." His father was a man of science; matter-of-fact, and analytical. Spielberg's mother, Leah, was the complete opposite.

"My mom was Peter Pan. She was a sibling, not a parent," Spielberg says in the documentary. He says that lovingly but if you stop and think about it, it's not exactly a positive description. Sure, it's great to have a "fun mom," but sometimes you need an actual parent. As he adds, "She was a best friend, not a primary caregiver."

It's easy to see why Spielberg blamed his father and took to the side of his mother in the divorce: Arnold was quite literally distant while Leah was more like a buddy than a mom. But Spielberg's idea of the divorce was skewed.

Daddy issues

As it turns out, Leah was the one who instigated the separation — because she had fallen in love with Arnold's best friend, Bernie Adler, someone the Spielberg kids thought of as an uncle. This was initially kept from Spielberg and his siblings, and in the "Spielberg" documentary, Arnold even states that he deliberately never told the kids that Leah divorced him — he let them think he divorced her. When asked why, he says he was "protecting her because she's fragile."

This marital subterfuge resulted in an estrangement between Spielberg and his father that lasted about 15 years and found its way into Spielberg's movies. The Spielberg dads are often prone to up and leave their family behind — husband and father Roy Neary blasts off to space at the end of "Close Encounters of the Third Kind." Elliott's longing for his absentee father leads him to befriend an extra-terrestrial in "E.T." And nearly every (male) Spielberg protagonist you can think of has daddy issues — even Indiana Jones.

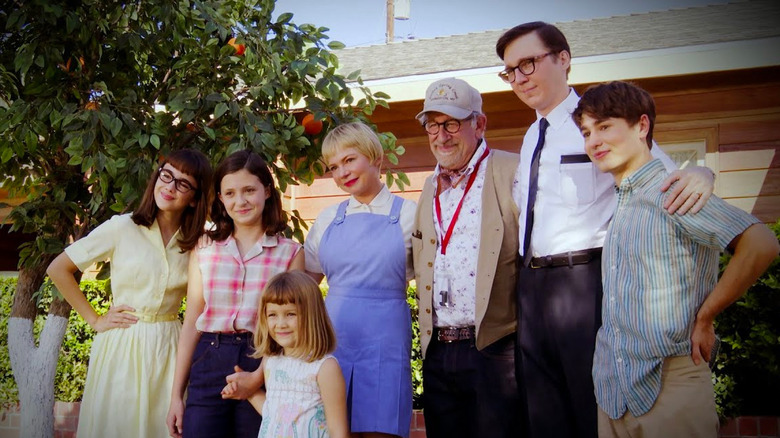

Spielberg would eventually reconcile with his father. And with "The Fabelmans," you start to think that not only is Spielberg telling the story of his own life, but he's also offering one last olive branch to his father, who died in 2020. The Arnold figure in the film, Burt Fabelman, played by Paul Dano, is committed to his work, and prone to uprooting his family to go wherever his job takes him. But he's also portrayed by Dano as a kind, sensitive man who ultimately ends up alone. Dano and Spielberg make this character wholly sympathetic, and there's a late shot in the film where Spielberg frames Dano from a low angle, surrounded by white space with a sad look on his face, and he appears to be the loneliest man in the world. Our heart breaks for him.

A communal mirror

That's not to say "The Fabelmans" is all about tossing Spielberg's mother under the bus. While the neurosis and emotional and mental issues plaguing the mother figure, Michelle Williams' Mitzi Fabelman, are front and center, Spielberg is also completely sympathetic to this character. He's just daring to show her as flawed. He's not blaming anyone here — he's just taking pains to not idealize either character. In essence, Spielberg is showing his parents for who they really were: flawed but loving human beings. Sure, they make mistakes. But so does everyone.

"I didn't want the story to be told in a vanity mirror," Spielberg said. "I wanted the story to be a communal mirror so people could see their own families inside the story. Because this story is about family; it's about parents; it's about siblings; it's about bullying; it's about the good and bad things that happen when you're growing up in a family that pretty much stays together until they're no longer together; and it's a story about the act of forgiveness, and how important that act is."

Stay professional

In "The Fabelmans," the Fabelman family act as stand-ins for Spielberg and his kin. While this is a dramatized series of events, it also sticks very closely to Spielberg's true story, or at least the true story he's willing to tell — late in the film, the director holds his camera on a poster for "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance," a film famous for giving us the saying "print the legend." Spielberg is printing the legend here; he's telling his story in the most cinematic way he knows how. He's also conducting his own version of a therapy session — the filmmaker gave multiple interviews stating that shooting some scenes of "The Fabelmans" moved him to tears.

"I made a promise to myself that I was going to stay professional," the director said. "There was going to be a distance between myself and the subject. But it was hard to do. The story kept tugging me back to actual memories. Recreating things that had actually happened to me, seeing them unspool in front of me, it was a wicked, weird experience. It was just like nothing I have ever gone through before."

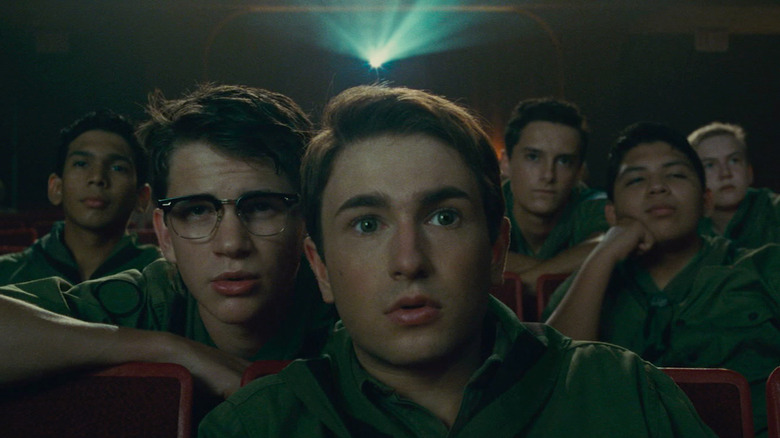

Spielberg's avatar in the film is Sammy Fabelman, played by Mateo Zoryan Francis-DeFord as a child and then by Gabriel LaBelle as a teenager and beyond. Like Spielberg, Sammy is introduced to the world of movies through a screening of Cecil B. DeMille's 1952 circus film "The Greatest Show on Earth." And like Spielberg, Sammy is afraid of the whole concept of going to the movies for the first time.

The Greatest Show on Earth

It's here, in the very first scene of the film, where Spielberg quickly establishes the clashing contrasts between Sammy's parents, Burt and Mitzi. Burt, ever the scientist, tries to explain what movies are by launching into a rambling, rather dry explanation of how movie cameras and projectors work. Mitzi, on the other hand, is more poetic, comparing movies to dreams and magic.

This setup isn't meant to say that Burt and Mitzi are instantly at odds. They clearly love each other — they're just very different people. While Burt loves his scientific work, Mitzi is the artist of the pair; she's an accomplished piano player and dreamed of being a professional pianist before the reality of getting married and having a family effectively killed those dreams.

Sammy watches "The Greatest Show on Earth" with awe, and is traumatized during a scene where a train smashes into a car and sends the automobile flying in the air. The traumatic incident morphs into an obsession, and when Sammy is gifted a train set for Hanukkah, he immediately begins crashing it on purpose, much to his parents' confusion. But it's the artistic Mitzi who figures out what Sammy is doing: he's trying to control his emotions by controlling the scene that haunts his thoughts. And so she hands her son Burt's camera and sets him down a path that will lead to his destiny.

Infatuated with the control

Again, this is all pulled directly from Spielberg's life. In "Spielberg: A Retrospective," the filmmaker states:

"I was infatuated with the control that movies gave me, in creating a sequence of events — a train wreck with two Lionel trains that I could then repeat and see over and over again. I think it was just a realization that I could change the way I perceived life through another medium, to make it come out better for me ... to see if what I was making was having an effect on anybody other than myself."

Sammy is instantly hooked on filmmaking and begins making home movies with his sisters. As he gets older (and is played by Gabriel LaBelle), Sammy is still making movies, using his friends and family as actors in elaborate productions. His mother is clearly impressed with her son's affinity for moving pictures, but Burt looks on all of this as a hobby; a flight of fancy that won't ever amount to much. It's not that he doesn't believe in his son. It's that his analytical mind can't allow him to think there's any real financial future in creating art.

Meanwhile, cracks in the foundation of the Fabelman marriage begin to widen and grow. When Burt gets a job in Arizona and has to up and move his family there from New Jersey, Mitzi is insistent that Burt bring along his best friend and co-worker Bennie, played by Seth Rogen. Sammy isn't privileged to this conversation, but Bennie does end up accompanying the family to Arizona. And it's here where Sammy finally begins to see through those cracks.

Dancing in the headlights

During a camping trip with the Fabelman family and Bennie, Sammy has his trusty camera at the ready. Again, Spielberg shows us the disconnect between Burt and Mitzi: while Burt is trying to teach his kids how to start a fire, Mitzi and Bennie can be seen in the background horsing around like big kids — and doing so in such a loud manner that the entire Fabelman family, save Burt, abandons the fire building to go watch.

Later that night, Spielberg gives us more insight into Mitzi and her mindset. For one thing, we see her sipping from a cup while a Jim Beam bottle is nearby. Then, Mitzi, seemingly drunk, insists on dancing in front of her entire family, illuminated by the headlights of the car. One of the Fabelman daughters is mortified, especially since Mitzi's nightgown is sheer enough to see through. But Burt, Bennie, and yes, Sammy, watch, transfixed.

It's a hard scene to read. You get the sense that Spielberg thinks it's magical, and indeed, the visual of Michelle Williams dancing in those headlights is a strong one. But Mitzi is also seemingly intoxicated, and there's an unspoken Oedipal element to Sammy watching his mother twirl around in a see-through outfit that enhances the moment in ways that I'm not entirely sure the filmmaker intended.

It'll tear your heart out and leave you lonely

The camping trip will end up being a catalyst, as will what happens after. Mitzi's mother dies, plugning her into depression and hearlding the arrrival of her Uncle Boris, played by Judd Hirsch. Boris is an artist — he worked in the movies in the 1920s, and before that, he was a lion tamer at the circus. Or so he says.

Burt wants Sammy to cut the footage from the camping trip into a movie to cheer Mitzi up, and it's this footage Sammy is working on when Boris visits. Boris sees the artist within Sammy. "You and me, we're junkies. Art is our drug. Family, we love. But art? We're mashugana for art," he tells Sammy, and then speaks something that all artists have likely thought at one point: he knows that Sammy loves his family, but he also knows that Sammy loves making movies more. Maybe just a little bit more, but still more.

Sammy denies this — who wants to admit they don't love their family as much as their work? — but in this dialogue you can see Spielberg grappling with his insecurities and loneliness. As Uncle Borris puts it, "Art will give you crowns in heaven and laurels on earth, but it'll tear your heart out and leave you lonely." Does Steven Spielberg, the most successful filmmaker of all time, feel lonely? Of course he does. Because his work is more than work to him; it's something sacred. It's something he gives himself entirely to. It's something others might not understand. And, most important of all, it's something he is able to exert control over.

Sammy exerts that control over the camping trip movie by creating a pleasant representation of family fun. But there's a director's cut of this movie: one in which Mitzi and Bennie can be frequently seen together in the background, embracing, holding hands, cuddling. The realization is slow to dawn on Sammy while he's editing the footage, and when he finally sees it, he jumps up and backs away from his editing machine as if he's just watched a jump-scare.

Marriage troubles

A coldness forms between Sammy and his mother, and when things boil over he finally shows her the cut footage. It becomes their secret, but it won't stay a secret forever. And when the family has to pack up and move again, this time to California, Bennie stays behind — a decision that alters Mitzi's entire personality.

While there's no medical diagnosis mentioned in the film, it's likely that Mitzi is suffering from manic depression or a bipolar disorder (the term "manic depression" didn't first appear in medical journals until the mid-50s, and therefore remained somewhat unknown to the general public at the time). Spielberg doesn't feel the need to actually diagnose his mother, he lets her actions speak for themselves. And Mitzi's playfulness and her violent mood swings suggest an underlying issue (there's a throwaway line, played for laughs, later in which she reveals she's finally going to therapy).

The first half of "The Fabelmans" is occasionally shaky. Much praise has been heaped on Williams' performance, and while I think she's a damn great actor, her work here is so dialed up to 11 that it begins to grate. I get it: this is who she is as a person; this is her personality. But it's the type of personality an outsider — someone outside of her family, that is — can find, well, irritating. Dano is much better here, trying his best to make Mitzi happy while knowing deep down inside that he can't; that it's Bennie she loves. Dano does a lot with a little, letting his pained-but-sympathetic expressions speak for him.

California

It's the final half of the film, when the Fabelmans arrive in California, that "The Fabelmans" truly comes into its own. Primarily because it's in this section of the film that Sammy's parents take a backseat and Sammy becomes more of a protagonist.

It's in California that Sammy gets his first real dose of antisemitism thanks to his high school classmates, particularly from Logan (Sam Rechner), a jock who looks like he stepped off an Aryan Youth recruitment poster. Spielberg is proud of being Jewish and is responsible for creating the USC Shoah Foundation, which creates audio-visual interviews with survivors of the Holocaust. But there was a time in the filmmaker's life where he felt ashamed of his Jewish roots. In the "Spielberg" documentary, he talks about how there was a period where he would essentially deny his Jewish roots. And in the same doc, his sister Anne states: "Steven did not want to be Jewish."

While the antisemitism is appropriately unpleasant in "The Fabelmans," there's never a moment where Sammy, like Spielberg, flat-out tries to deny his Jewish identity. There's a moment when he angrily tells his father that he feels like an outcast because they're the only Jewish family for miles, but that's not quite the same as trying to shrug off one's identity.

"Part of the reason that we bonded during 'Munich' the way that we did was that we both have a very powerful, bone-deep love of being Jewish and Judaism," said Tony Kushner. "That was just going to be part of what the story [of 'The Fabelmans'] was going to be — a story about a Jewish family."

A handsome Jewish boy

The high school section of the film also leads to one of the funniest sequences Spielberg has ever crafted. Sammy catches the eye of Monica (a scene-stealing Chloe East), a Christian girl who seems to treat Sammy as an almost fetishistic object because he, like her hero Jesus, is a "handsome Jewish boy." The first "date" the two have amounts to Sammy being forced to pray after being given a tour of Monica's bedroom, the walls of which are plastered with images of handsome guys (including Jesus).

This portion of the film also results in a sequence that seemed to puzzle some viewers. Sammy is encouraged to use his filmmaking prowess to film Ditch Day, in which seniors blow off school en masse and head to the beach. Sammy films the events and premieres the results at the prom — after blowing his chances with Monica by practically proposing to her. Sammy's film is funny and charming, but it also portrays his bully Logan in a heroic light. Logan is ultimately the star of the film, a fact that confuses the bully to no end. He confronts Sammy in the high school halls after, demanding to know why Sammy did what he did. And some viewers had the same question — why would Spielberg glorify an antisemtic bully this way?

But he's already given us the answer: it's all about control. Movies are the way that Sammy, and Spielberg, take command of things outside of their control. Through his camera lens, Sammy is both shaping the world as he wants to it be while essentially hiding from the real world. In real life, Sammy is a bullied kid watching his parents drift apart. In the world of his movies, anything he wants is possible.

Sammy himself may not even realize this, though. When pressed for an answer he first says he cut the film this way because he wanted Logan to be nice to him for a change, but then he quickly adds that he really doesn't know why he did what he did. He just did it. Because it felt right for the movie. Every movie needs a hero.

The gulf

In the midst of all this, the gulf growing between Burt and Mitzi becomes too vast to bridge. Spielberg continually gives us loaded images to heighten the divide. After watching one of Sammy's movies — a World War II epic made with friends — Burt turns to comment on the film to Mitzi. But the second he does so, Mitzi turns away to talk about the movie with Bennie, who is sitting on her opposite side. When she does this, Spielberg has the camera pan over so that Mitzi and Bennie are in frame and Burt is completely absent, as if he vanished.

Later, when the Fabelmans move to a new house in California, the entire clan rushes into the abode to check things out, but Mitzi hangs back, lurking int he doorway like a vampire waiting to be invited in. Eventually, Burt picks her up to carry her over the threshold while Sammy films it all. And while Burt looks happy as can be carrying his wife, Mitzi's smile looks forced, and she flashes a rather sad look to the camera in her son's hands.

Mitzi is an emotional wreck without Bennie, and so the Fabelmans decide to split up, much to the tearful horror of their children. But again: Spielberg is taking pains not to blame anyone here. Yes, the decision is ultimately arrived at because Mitzi is in love with someone else. But Spielberg also gives the character a coda in which Mitzi tells Sammy that she knows what she's doing is selfish, and that Burt deserves better — but she has to do it because she has to follow her heart. We all do. It's the payoff to an early scene with Uncle Boris, in which he tells Sammy about how Mitzi abandoned her dreams of playing the piano professionally. She didn't follow her heart then, and now she is. She's doing what she feels is right for her, because the heat wants what the heart wants, as the saying goes. Selfish? Sure. Realsitic and understandable? Of course.

Where's the horizon?

This, perhaps, would've been a fine finale for the film. But Spielberg still has one great magic trick up his sleeve, giving us an ending that's meticulously crafted to bring a smile to our faces. A year later, after having enough of college and dreading his future, Sammy gets invited to a job interview at CBS. But it's not TV Sammy wants to work in — it's motion pictures. And as it so happens, one of the best filmmakers to ever do it has an office nearby, and Sammy is brought over for some advice.

That director is John Ford, and Spielberg scores a coup by casting David Lynch in the role. Lynch's approach to playing Ford is essentially "David Lynch, but angry," and it works like gangbusters. This is a story Spielberg has told several times over his career — the story about how he met John Ford, and how Ford asked him to look at two paintings on his wall. In "The Fabelmans," like in real life, the paintings are Western scenes, but Ford isn't interested in their content. He just wants to know where the horizon is.

The horizon is at the bottom in one image, and at the top in another. And that's all the advice John Ford needed to give young Steven Spielberg and Sammy Fabelman. When the horizon is at the top, it's interesting. When the horizon is at the bottom, it's interesting. When the horizon is in the middle? Well, that's boring. And with those words of wisdom, Sammy strolls out onto a studio lot, his filmmaking career stretching out in front of him.

'This is the hardest film I've had to say goodbye to'

I will admit I expected Spielberg to go a little further. To stick with Sammy as he breaks into TV and then the movies. But this is ultimately the perfect place to end the story — Sammy's parents have split up but he's in a better place with both of them. And his future is bright. Now if only we could've gotten a post-credit scene where Spielberg's avatar meets a stand-in for George Lucas. Oh well, save it for the sequel.

"This is the hardest film I've had to say goodbye to," Spielberg said. "I cannot even imagine going through my career without having told this story. This movie, for me, was like a time machine, and to have that time machine suddenly turn off, and now all the memories are locked into place, and they have an order, they're going to be edited together, and that's going to be it ... well, as Thomas Wolfe said, and he's right, 'You can't go home again.' And I realized at the end of shooting 'The Fabelmans' that I would never be able to go home again. But at least I've got this to share."

"The Fabelmans" is unquestionably the most personal film Spielberg has ever made. It's also pretty damn wonderful, and more proof that even at this late stage of his career, Spielberg is still swinging for the fences and knocking it out of the park in the process. That said, the film also feels like something of a stepping stone. Or rather, it feels like something Spielberg had to finally get out of his system. A cinematic therapy session. He's spent decades talking about making this movie, and now he finally has. And since he's a workaholic, he can't stop, won't stop. And I can't wait to see what he does next.