Wes Craven Wanted A Nightmare On Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors To Be Even Darker

Among horror fans, "A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors" is generally regarded as one of the best entries of the fantasy slasher franchise, which is now nine films deep. It's the entry that cemented Freddy Krueger as the wisecracking child killer he's known as now, an evolution that took creator Wes Craven's original concept and expanded it to give his monster more commercial appeal.

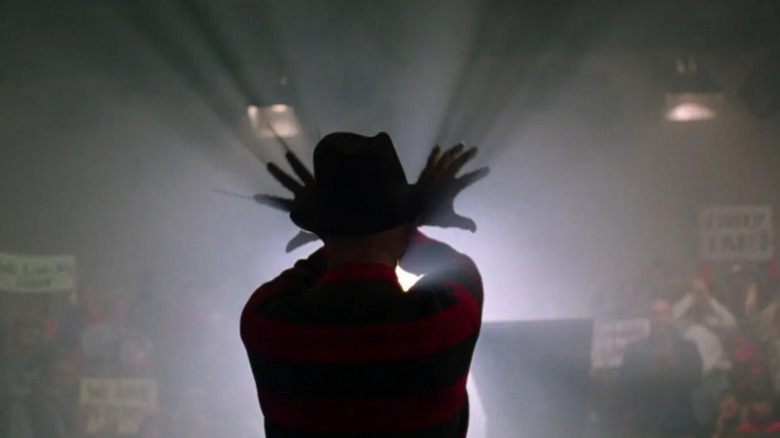

The third installment comes along on the success of "A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge," a sequel that, like its predecessor, follows a teenager battling the evil spirit of a scarred, blade-gloved child killer. Freddy operates in the dream world, and his signature striped sweater and filthy brown fedora are often the last things his victims see before their dream death and corresponding real-world death. New Line Cinema struck gold with the "Nightmare" movies; their baddie, unlike the hulking Jason Voorhees or strong, silent Michael Myers, had a clear identity. This villain's penchant for wordplay ("This is it, Jennifer: your big break in TV" he tells a victim before smashing her headfirst into a set) would prime the pump for another mouthy, more pint-sized offender named Chucky to come along in 1988.

Freddy's wisecracks and spotlight-hoarding intensified after Wes Craven stepped back from Elm Street, and while Jack Sholder's 1985 sequel did just fine at the box office, New Line wanted the original creator — and director of cult horror hits like "The Hills Have Eyes" and "Last House on the Left" — to reprise his role for the next chapter. By the time Craven returned to handle the story, he was keen to bring his monster back to his darker roots.

From director to writer to story by

Wes Craven, at this time, was still running on the success of 1984's "A Nightmare on Elm Street." His latest project, the bot-gone-bad horror "Deadly Friend," had fallen into his lap via producer and "Nightmare" fan Bob Sherman, who held the film rights to the bonkers story. The movie would keep Craven from sitting in the director's chair for NOES 3, so New Line Cinema hired Chuck Russell to make his feature directorial debut.

In the meantime, Craven was still attached to pen the screenplay, a task he shared with writer Bruce Wagner on account of the writing process running concurrently with delivering the first cut of "Deadly Friend." The AV Club quotes Craven as returning to the Elm Street universe "because [he] felt compelled to come back and expand the original concept." That is, reminding audiences that Freddy's grotesqueries weren't limited to whatever the special effects team could conjure up; this was a monstrous predator long before he got those burn scars.

Craven's original draft with Wagner was eventually re-worked, decimating the creator's iteration of Part 3 down to a "Story By" credit. Director Chuck Russell would be assigned the re-writes with Frank Darabont, a collaboration the two would repeat for Russell's 1988 sophomore feature, "The Blob." Both their draft and the Craven-Wagner draft are available from the online Nightmare on Elm Street Companion in tidy PDFs for your reading pleasure, but Craven sums it up in the Companion,

"They changed it quite drastically in some ways. The director and a friend of his rewrote it and changed the names of all the characters, and included several key scenes of their own. A lot of the reasons I had agreed to do the picture were taken away."

No more backstory needed for this Boogeyman

A quick read of the Craven-Wagner draft reveals key differences in its handling of Freddy Krueger. The copious zingers that had come to mark a Freddy killing are few and far between; instead, the "Scream" director kept remembrance of Freddy's malevolent nature.

Mother-of-the-final girl Marge Thompson (Ronnie Blakely) delivers the backstory in the first "Nightmare on Elm Street," characterizing Freddy as "... a filthy child murderer who killed at least 20 kids in the neighborhood" and whose actions earned Krueger an agonizing, flaming death. In Craven's telling, Freddy's crimes are more explicit; an early scene observes a teen hitchhiker naming her destination as down, "down where he ****s you."

Not only would Marge's daughter Nancy (Heather Langenkamp) return in Russell's film, but her role would be expanded from one teen to a cadre of hardened misfits — the Dream Warriors — each with their own dream-realm superpower, tasked with defeating the Bastard Son of 100 Maniacs. It was one of the "imaginative elements" of Craven's story that appealed to the re-writers, as Chuck Russell would put it. "It had to be a group," Russell continues, "because the souls of Freddy's victims have made Freddy stronger."

Freddy's strengths manifested in more shapeshifting for Craven's Freddy and less mythmaking. While both the original script and the finished feature would showcase a group of kids in a mental hospital, the return of Nancy Thompson, and a highly phallic Freddy snake, only the former would have Krueger morphing into a dog and a crow, and only the latter would feature slasher-mom Amanda Krueger expositing Freddy as the product of gang rape. As fine as it is to see franchise material return to the hands of its originator, it's also hard to imagine "Dream Warriors" replicating its multimillion-dollar box office triumph with Craven's more-bite-and-less-bark Krueger.

What could have been

Scratch the surface of the old genre magazine backissues and you'll uncover an alternate synopsis for one of your favorite horror movies. A September 1986 interview with Fangoria Magazine catches Wes Craven at the terminus of production for "Deadly Friend," when he was on the cusp of co-writing the new NOES picture. Dismissing the canon of the last entry, "Freddy's Revenge" ("I'm ignoring it," Craven curtly replies), the writer-director offers a juicy pitch that would have given genre mainstay and fan favorite John Saxon ("Cannibal Apocalypse"), who plays Nancy's unhelpful father, a much meatier role in the franchise. He tells Fangoria:

"The plan is to bring back Nancy and her father. I don't want to give too much away here, but basically, the back story is that the father was a very straight guy who never believed any of this stuff was possible. When he glimpses his wife being dragged through a bed and disappearing and sees the rest of what happened, his entire life is changed. He pursues Freddy back through Freddy's past to the house where Freddy was born. Nancy follows her father who has essentially gone mad and left his job. They both end up in the house of Freddy."

Returning to Craven indicates a back–to–basics approach, but the director also wanted to broaden the horizons of the world he crafted, "exploring not only dreams but other states of altered reality within the human consciousness." It's a fascinating concept that leaves Elm Street kids not only vulnerable to Freddy when they sleep, but during any "special psychic state" or heightened madness, which makes the primary setting of a mental institution an inspired choice; it's no wonder why Russell and Darabont hung onto that during the revision phase.

Wes Craven's deferred nightmare

John Saxon fought alongside Bruce Lee in "Enter the Dragon," it should be noted. So as much as any of us want to see him fight an erect Freddy snake, the "Nightmare on Elm Street 3" we got is the one that serves as the master pattern for the Freddy that America reveres and recoils from with equal measure. Craven's script had a finger on the pulse of pop culture; it originally called for the killer to squeal, "Herrrrre's Freddy!" like Jack Torrance during the famous kill scene. But it's hard to say with certainty that Craven's story would have matched the popularity of Russell's nightmare.

On one hand, slasher movies were taking chances in the late '80s. Just one year after the Dream Warriors entered the fray with Freddy, audiences would see Jason Voorhees fighting a psychokinetic teen in Part VII of the "Friday the 13th" franchise. The "Halloween" franchise would simultaneously introduce its divisive "Thorn" narrative that gave Michael Myers a psychic connection with a blood relative, and a supernatural connection with a local Druid cult. If there was a time for someone to re-calibrate Freddy as more monster than emcee, 1988 would have been the year for it.

On the other hand, the NOES sequels were popular because of Freddy, not the other way around. It was the third franchise entry in which a clear turn towards stardom and a charismatic persona could be seen; just look at this interview from the set of "Dream Warriors"; Freddy's ready for his close-up with Johnny Carson. His popularity would soon spawn an anthology tv series and a Nintendo tie-in; it's unlikely that he has matured into the adored icon that America now celebrates, but Craven's always chosen the darker timeline, hasn't he?