10 Classic Sci-Fi Novels That Need To Be Adapted Into Movies

Science fiction movies have shared a close relationship with their literary counterparts for as long as they've existed. The first sci-fi film ever made, Georges Méliès' 1902 short "A Trip to the Moon," was inspired by two Jules Verne novels, "From the Earth to the Moon" and "Around the Moon," as well as H.G. Wells' serialized novel "The First Men in the Moon." From there, countless movies — including some of the greatest of all time — have been based on sci-fi novels, novellas, and short stories.

Let's put it this way: Without the vast cosmos of sci-fi literature to draw from, we would never have experienced "Metropolis," "Frankenstein," "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," "2001: A Space Odyssey," "A Clockwork Orange," "Solaris," "Planet of the Apes," "Blade Runner," "Total Recall," "Starship Troopers," "The Thing," "Jurassic Park," "Minority Report," "Children of Men," "Arrival," "Annihilation," "Edge of Tomorrow," and a hell of a lot more.

Clearly, books have made an invaluable contribution to the world of cinema over the last 120 years, but there are still many worlds left to explore. Here are some classic sci-fi novels that, despite being ripe for adaptation, have yet to receive their moment on the silver screen.

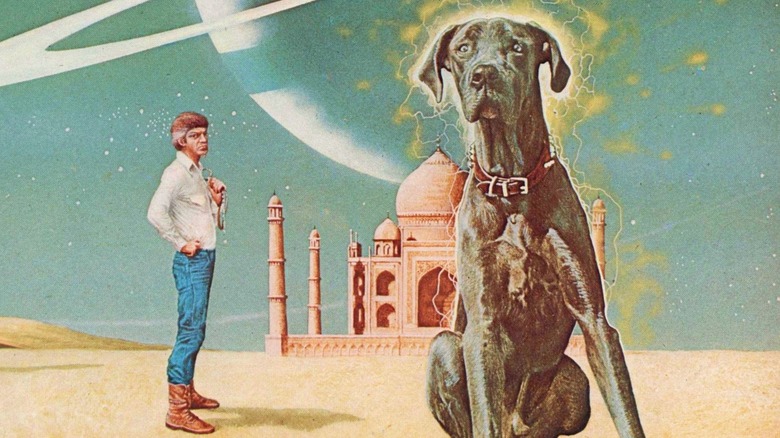

The Left Hand of Darkness — Ursula K. Le Guin

"The Left Hand of Darkness" is arguably the most famous of the 19 stories that make up Ursula K. Le Guin's Hainish Cycle. Published in 1969, the novel is set in a future in which much of the known universe has banded together to form the Ekumen, a loose federation of worlds that provides trade, knowledge, and protection to its members. Genly Ai, a Terran envoy for the Ekumen, is sent to the planet Gethen — known to his people as "Winter" — to convince the native population to take their first steps into the wider universe.

Le Guin's book is particularly well-suited for film because it so deftly strikes so many different chords at once. In one sense, it's a political thriller, as Genly struggles to navigate Gethen's different factions and convince their leaders to join his cause. In another, it is a study of gender; the inhabitants of Gethen are ambisexual, only adopting "male" or "female" traits once a month, and Le Guin uses this quality to shine a light on our own attitudes towards masculinity and femininity. "The Left Hand of Darkness" also features a love story for the ages, as Genly and Estraven, an exiled politician, fall deep into a discordant and passionate romance. And then, seemingly out of nowhere, the back end of the novel explodes into a gripping adventure story, forcing the two lovers to race against time across Winter's northern ice sheets.

A mission for peace; a strange alien civilization; a doomed romance; a stirring third-act escapade — and it's all combined with some of the finest world-building this side of J.R.R. Tolkien. It's a marvel that "The Left Hand of Darkness" hasn't been adapted a dozen times already.

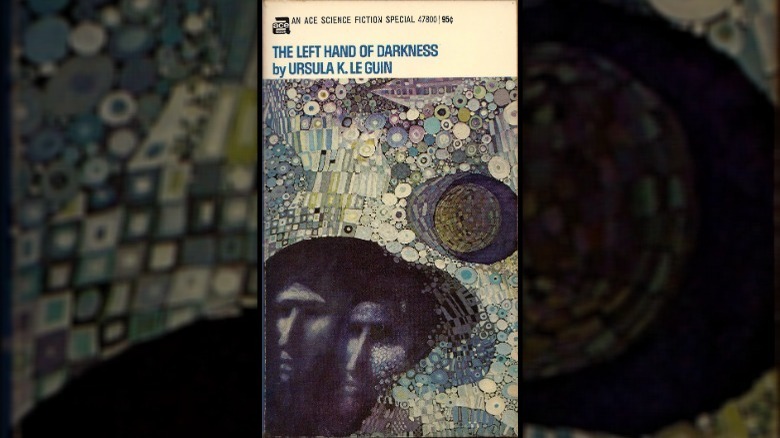

The Blazing World - Margaret Cavendish

Mary Shelley is often (and rightly) considered to be the mother of science fiction, but the genre's foundations were laid long before "Frankenstein." In 1666, English writer Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, published "The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing-World." The story follows an unnamed "Lady" who, after journeying through a passageway near the North Pole, finds herself lost in a utopian world populated by anthropomorphic beasts. Crowned Empress of the Blazing World, the Lady launches a military invasion to rescue her homeland from an existential threat. Cavendish's groundbreaking novel was actually the very loose inspiration behind "The Blazing World," a 2021 thriller about the traumatic homecoming of an American college student. Still, that movie is sorely lacking in talking animals, arctic exploration, and naval warfare, so it's hard to argue that it's a real adaptation of the original story.

It's a real shame that we've never had a proper "Blazing World" film, too. While the book isn't exactly an easy read — it's very obvious that it was written in the mid-17th century — it is a staggeringly imaginative work, one that feels bold and fantastical even by today's standards. It's also surprisingly exciting: The middle of the novel gets a little bogged down in philosophical navel-gazing and meta commentary, but the second section, in which the Empress clothes herself in bejeweled robes and leads her golden submarines to the shores of Europe, is a genuine thrill. Give it to Guillermo Del Toro and watch the awards pile up.

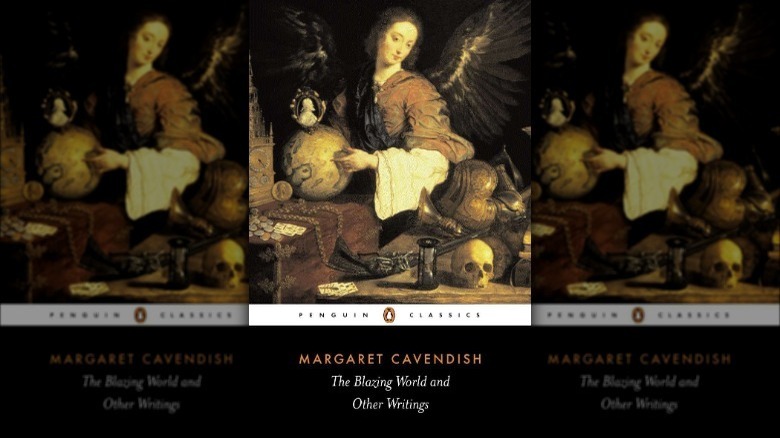

The Sirens of Titan — Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut's sophomore novel is considered by many (and by "many," I mean "me") to be the finest work of sci-fi comedy ever made. Released in 1959, "The Sirens of Titan" revolves around Malachi Constant, an ultra-wealthy and incredibly fortuitous businessman who is given a bizarre prophecy by an omniscient space explorer. During his fruitless attempt to flee his fate, Constant is caught up in a Martian invasion of Earth, the establishment of a global religion, and a final, devastating journey to Titan itself.

"The Sirens of Titan" tackles a number of heavy themes across its 300-or-so page count, from the nature of free will to the meaning of life itself, but what really strikes you is just how much fun it all is. Vonnegut's ability to balance the hilarious with the heartbreaking is beyond compare, and his uncanny knack for clever dialogue and absurdist humor could, in the hands of a capable screenwriter and director, make for a truly wonderful sci-fi movie.

It does bear mentioning that we've come tantalizingly close to a "Sirens of Titan" adaptation before. Back in 2017, Variety reported that "Community" and "Rick & Morty" creator Dan Harmon had been hired to develop a TV series based on Vonnegut's book. He was still writing scripts for the show during a GQ interview in 2018, but nothing has been said about it since then. For now, it seems, the adventures of Malachi Constant will remain confined to the page. What a shame.

We — Yevgeny Zamyatin

A number of dystopian sci-fi movies have come from books. The most famous, of course, is "Nineteen Eighty-Four," Michael Radford's adaptation of the George Orwell classic, but countless others exist too, including "The Road," "Children of Men," and the "Hunger Games" franchise. "We," the 1921 novel by Yevgeny Zamyatin, might not be as recognizable as some of those names, but the novel's influence on the genre is undeniable: Orwell himself believed that it inspired Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World," and he lifted more than a few of its beats for his own story.

"We" is about D-503, a spacecraft engineer who lives in the One State, an authoritarian dystopia defined by mass surveillance, total subservience, and the worship of logic above all. When D-503 meets I-330, a charming rebel who claims to be part of an underground movement to overthrow the One State's dictator, he finds himself torn between his duty and his growing desire for freedom. If this all seems a little derivative, know that it's only because Zamyatin did it before anyone else — Kurt Vonnegut once said that, in writing his own dystopian novel, "Player Piano," that he "cheerfully ripped off the plot of 'Brave New World,' whose plot had been cheerfully ripped off from Yevgeny Zamyatin's 'We.'"

While we've seen many adaptations of the stories that "We" influenced, Hollywood has yet to breathe new life into the original. (A Russian version was supposed to release in 2021, but seemingly has yet to see the light of day.) As events in the real world become ever more, uh, interesting, works such as "Nineteen Eighty-Four" and "Brave New World" are being brought closer to the fore of the cultural zeitgeist. Why not go back to where it all began?

Kindred — Octavia E. Butler

Thanks to the efforts of creators like Jordan Peele, Nia DaCosta, and Misha Green, Black-led horror movies and shows have experienced something of a boom in recent years. Aside from a few noteworthy projects, however — "Black Panther," maybe, or "Sorry to Bother You" — Black science fiction has yet to find much mainstream success at the movies. This is a particular shame, since Black authors have been producing fantastic sci-fi literature since the advent of the genre.

Take "Kindred," for example. Written by legendary sci-fi author Octavia E. Butler, "Kindred" is rooted firmly in the history of Black America. The story follows Dana, a young writer who begins to inexplicably flit between modern day Los Angeles and a Maryland plantation in the 1800s. Over time, Dana's trips to the past become longer, forcing her to reckon with the brutality of slavery and its impact on her ancestors.

By depicting slavery through the eyes of a contemporary protagonist, "Kindred" offers a unique take on a story that has rarely been done justice on the silver screen, and Butler's complex portrayal of slave communities is remarkable even today. It's fair to say that faithfully adapting Butler's novel into a feature would be difficult (Hulu made a disappointing attempt at a TV series in 2022), but, if someone succeeded, it would almost certainly be a stunning success — and could kick-start the golden age that Black sci-fi cinema deserves.

The Restaurant at the End of the Universe — Douglas Adams

In 2005, Garth Jennings directed an adaptation of Douglas Adams' iconic sci-fi novel, "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy." Although many critics would disagree, I'm actually a big fan of the "Hitchhiker's Guide" movie — despite making a few key changes to the plot of the book, it's absolutely stuffed with heart and feels Adamsian to its core (probably because he co-wrote the screenplay prior to his death). Sadly, despite ending on a sequel hook, a second installment never materialized; in 2007, Martin Freeman told MTV that the first simply didn't do well enough to warrant another.

It's too bad, too, because "The Restaurant at the End of the Universe" is just as funny and irreverent as "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy." In the second installment in the five-book series, Zaphod Beeblebrox and Marvin the Paranoid Android set out to meet the Ruler of the Universe, Arthur Dent and Ford Prefect journey to prehistoric Earth, and the whole gang visits the eponymous restaurant, where diners are able to witness the destruction of the universe itself. It's all deeply weird — weirder even than "Hitchhiker's Guide," though not nearly as absurd as the subsequent books in the franchise.

Honestly, I'm not sure how well "The Restaurant at the End of the Universe" would translate to the screen. Certain aspects were adapted into the superb "Hitchhiker's Guide" TV show from the early '80s and the radio series that preceded it, but in those cases the story acted more as a middle chapter in a larger narrative. Could anyone actually pull off a straight, standalone adaptation? Maybe, maybe not. All I know is that the original 2005 movie absolutely deserves a sequel.

Downbelow Station — C.J. Cherryh

"Downbelow Station" is part of C.J. Cherryh's epic Alliance-Union universe, a series of 27 novels and seven short story anthologies that detail the conflict between a private corporation called the Earth Company, the trade confederacy known as the Alliance, and the Union, a rebel government based on the distant world of Cyteen. Published in 1981, the first novel in the saga depicts the final days of the war as experienced by the denizens of a space station orbiting Pell's World, which the residents call "Downbelow."

To say that Cherryh's universe is complex would be an understatement. Beneath the dense world-building and politicking that drives "Downbelow Station," however, you'll find a sprawling human drama played out by a compelling cast of characters. That's the novel's brilliance, really: The reality of this cosmic war always feels intimate, and the people affected by it — whether they're soldiers, refugees, or otherwise — are fully-realized and believable. Nevertheless, it all leads towards a spectacular climax filled with betrayal and destruction, one that justifies the slower first half and then some.

It's easy to imagine "Downbelow Station" as a kind of "Game of Thrones"-style streaming series, but it's arguably just as suited to the movies. A film adaptation could easily stand as a tense and claustrophobic one-off about the social trauma wrought by war, or it could play into the space opera angle, kick up the action, and spark a whole franchise. Either way, the best aspects of Cherry's novel would work marvelously in cinema.

The Drowned World — J.G. Ballard

Back in 2016, Ben Wheatley brought J.G. Ballard's most famous sci-fi book, "High Rise," to the big screen. Despite that movie being genuinely pretty great, I would argue that he chose the wrong story. The author's second novel, 1962's "The Drowned World," is a striking and strangely beautiful portrayal of an environmental post-apocalypse, one that might have as much of an impact on a 21st century audience as it would a 20th century reader.

Set in London in the 22nd century, "The Drowned World" takes place long after an array of solar storms have played havoc with the Earth's ionosphere, leading to rapid global warming and flooding most of the planet. Dr. Robert Kerans, a scientist tasked with studying the prehistoric creatures and plants that have emerged in the sunken city, begins to dream of ancient lagoons, giant beasts, and an ever-thrumming sun — and soon finds that his companions are experiencing the same visions. Kerans' regression into his biological roots only becomes more complicated by the arrival of Strangman, the terrifying leader of a band of pirates and, if you ask me, one of the genre's most underrated villains.

In "The Drowned World," Ballard weaves a vision of the future that feels so utterly oppressive that it's almost hypnotic, rife with abandoned skyscrapers and giant lizards; visually, it could give any sci-fi classic a run for its money. That's to say nothing of the story's focus on climate, too, which would no doubt resonate in a world that is, if not quite drowned, certainly getting there. Few literary adaptations would feel more timely.

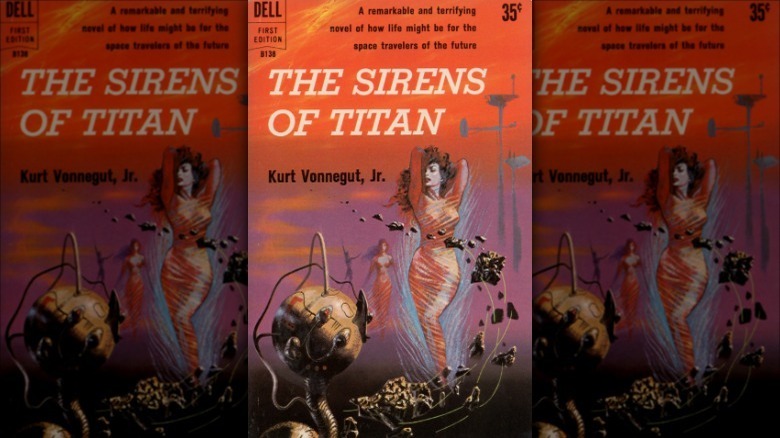

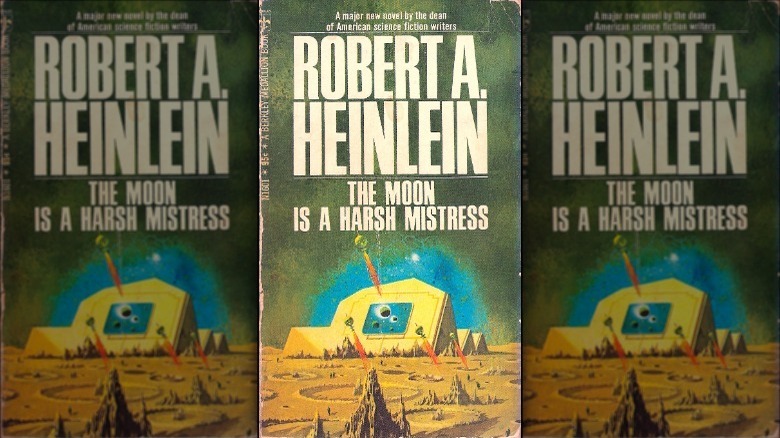

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress - Robert A. Heinlein

Published in 1966, Robert A. Heinlein's "The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress" tells the tale of a revolutionary war waged against Earth by a lunar colony. Guided by a sentient supercomputer named Mike, the so-called "Loonies" declare independence from their masters after realizing that the wheat tributes they send to Earth will eventually lead to the collapse of their burgeoning civilization. The leaders of the uprising, Mannie, Wyoh, and Prof, subsequently find themselves in a world of intrigue and oppression.

Above all, "The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress" is a careful examination of the politics of rebellion. Heinlein tackles many subjects in the novel, from gender relations to economics, and spends a good deal of time opining on each. This is not why it would make for such a good film, though — in fact, I would say any movie adaptation would do well to cut most of that out. No, "The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress" earns its place on this list because the basic premise — moon-people build society, Earth oppresses them, war breaks out — holds so much potential. As such, it really doesn't need to be faithful to the original story; simply hire a bunch of A-listers, throw half the budget into pyrotechnics, and let the good times roll.

That said, this is also another book we can chalk up as a near-miss in Hollywood. Back in 2015, The Hollywood Reporter revealed that Bryan Singer had been signed on to direct a movie adaptation of Heinlein's novel, titled "Uprising." Considering Singer's well-deserved fall from grace in recent years, though, this is probably another project that won't be arriving in theaters any time soon.

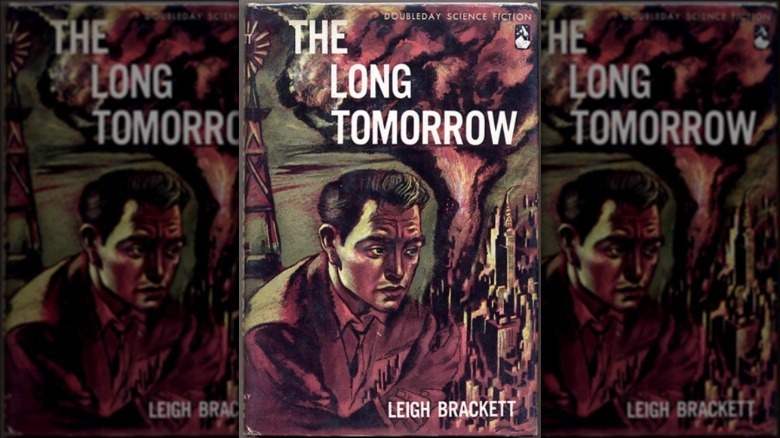

The Long Tomorrow — Leigh Brackett

Leigh Brackett was no stranger to Hollywood. Once described by Gizmodo as the "Queen of the Space Opera," Brackett's name is best known to cinephiles as an early contributor to the screenplay of "The Empire Strikes Back." She was an author first and foremost, however, and her 1955 novel "The Long Tomorrow" is one of her definitive sci-fi works.

"The Long Tomorrow" takes place in a world ravaged by nuclear war. In the aftermath, the few survivors have developed an innate hatred of technology, and the gap left by the absence of modernity has been filled by religious fundamentalism. The story follows two rebellious teenagers, Len and Esau, who set out to find Bartorstown, a distant community that is said to wield the power of old technology. Aside from the obvious science-versus-religion motif, there's a kind of post-apocalyptic Mark Twain vibe to "The Long Tomorrow," albeit with a healthy dash of "The Road" mixed in for good measure.

It's unlikely that a cinematic adaptation of Brackett's novel would become a smash-hit blockbuster, but the world of "The Long Tomorrow" is so captivating — and the themes so familiar even today — that the opportunity is simply too good to pass up.