The Dream Comes True: The Birth Of Disney Brothers Studio

(Welcome to 100 Years of Disney Magic, a series examining the history, achievements, and legacy of The Walt Disney Company over the last century. Part 1, "How Walt Disney's First Cartoons Drove Him To Bankruptcy," followed the animator's early life and first forays into the business. In Part 2, we explore the founding of Walt's second — and much more successful — company, Disney Brothers Studio.)

The Walt Disney Company is arguably the most influential media empire of the 21st century, enjoying a firm hold on the public's attention. This is a studio that is a true market maker. People care so much about the Disney business that social media was set ablaze in 2022 by the news that Bob Iger would return as CEO of the Walt Disney Company. With the possible exception of Warner Bros. (and the DC Films IP), what other company has so many non-industry people invested in the corporate leadership?

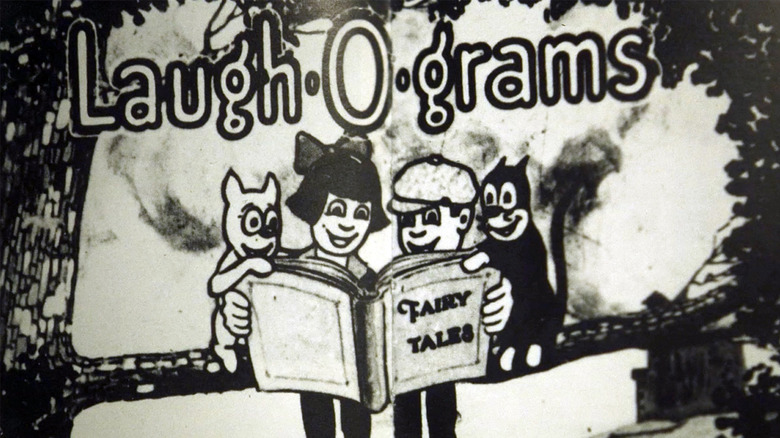

Yet, for how impressive and mindbogglingly massive "Disney" — and everything the brand name signifies — is today, the company is rooted in abject failure. Overly optimistic and lacking practical experience (both as a filmmaker and as an entrepreneur), Walt Disney swung for the fences with his first animation studio and struck out. His Newman Laugh-O-grams were sold with no profit margin. The six-picture deal with Pictorial Clubs resulted in disaster: Despite delivering six fairy-tale animations, the distributor went bankrupt before paying the promised $11,000, which Laugh-O-grams desperately needed. Walt's final Hail Mary, a combination of live-action and animation called "Alice's Wonderland," was unfinished when the money run out, and it — along with every other asset the company had — fell into the possession of creditors.

It's ironic that Laugh-O-grams failed because distributors did not see cartoons as something people would pay for, yet today, we retroactively view Disney as the studio that breaks box office records specifically with animated films.

Hollywood beckons Walt Disney

Significantly poorer but ultimately wiser, Walt Disney dealt with his Kansas City failure by moving on, figuratively and literally.

When Walt landed in Los Angeles in August 1923 in a borrowed suit with a battered, cardboard suitcase, he had little but optimism, determination, and sheer pluck in his favor. With just $30 in his pocket and drawing equipment, he didn't have much to show for himself. Disney had very few contacts in Hollywood, and there wasn't a strong "animation" scene on the West Coast. Still, as Neal Gabler writes in "Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination," the "city of dreams" was the best place for Walt — but he didn't know that yet.

The years of struggle in Kansas City had left their mark on Walt. When he returned to Kansas City from France back in 1919, he surprised his family with his acquired manly bulk. Now in 1923, with Roy seeing his brother for the first time in years, the opposite was true. Walt appeared shrunken and gaunt — no doubt exaggerated by his well-worn clothes hanging off his thin frame.

Despite Disney's characteristic dogged determinism, his intention in coming to Hollywood was not to establish another animation company. Perhaps his confidence had taken a blow (although by all accounts, it didn't show if it did), or maybe the failure of Laugh-O-grams Fims, Inc. just left a sour taste in his mouth. Either way, the next step for this artist-turned-animator was to break into the motion-picture industry another way: becoming a live-action director.

Lights, camera, action!

Walt Disney had a taste of directing back in Missouri. Working as an artist for the Kansas City Film Ad Company, he was exposed to not only animation, but also the world of cameras, actors, and live-action filmmaking. He dabbled in the occasional project with coworker Hugh Harmon, experimenting with the kind of short gags and visual tricks you'd expect from a 19-year-old go-getter learning the medium (Kay Cee Studios, they called it). They even got the opportunity to capture newsreel footage of the American Legion convention: one of Walt's contacts had an office across the street where they could film from. Opting to go the extra mile, Walt rented a plane hoping to capture dynamic aerial shots, but then inadvertently underexposed the film, leaving them with nothing to show for their work. Walt wasn't always successful, but he was endlessly ambitious.

Live-action filmmaking was technically difficult and outside of Walt's strengths, but it was much cheaper than animation. It was also, in some ways, easier to sell — as Disney learned the hard way when Laugh-O-grams struggled to find business. Given that, it makes sense that he would have gone to Los Angeles and not New York City, the cartoon capital. Still, it took Disney some time to get his bearings in Hollywood. Hoping to break into what was already a company town, he spent the first two months visiting studios, trying to network, and asking producers for advice. He even considered acting. When no paid work materialized, the no-doubt increasingly desperate Disney fell back on what worked in Kansas City: he approached theater owner Alexander Pantages about making short animated gag reels for promotional purposes. This project would soon be abandoned, however, when an old Laugh-O-grams venture proved fruitful.

Animation or live-action?

It's up to some debate what, exactly, was going through Walt Disney's mind when he arrived in Los Angeles in 1923. It's here in the story that the biographies by Gabler and Bob Thomas ("Walt Disney: An American Original") differ slightly. Essentially, both suggest that Disney came to California looking to be a director because he felt it was too late to get into the cartoon business. When he failed to find a place for himself at one of the studios, he decided cartoons were his best (possibly only) option, so he shifted strategies. He sought a deal for the crude joke reel animations he could make on his own, and he touched base with distributor Margaret Winkler (M.J. Winkler Pictures), whom he'd been in contact with since May (before Laugh-O-grams folded).

Walt arranged for Jack Alicoate, a well-connected intermediary on the East Coast, to send out the "Alice's Wonderland" print. Once Winkler finally got a chance to screen it, she "pounced" on the opportunity (per Gabler). The reasons for the delay and the resolution are too complicated to get into here, but it comes down to problems arising from Laugh-O-grams' bankruptcy procedures and rights issues. Walt was able to get "Alice's Wonderland" released to show Winkler, but he was starting over from scratch.

At the end of the day, it seems likely that Walt had both decided to move on from animation (and was not looking to establish a new studio in Hollywood), but also was the kind of enterprising young man who never left money on the table.

So why did Walt go to Hollywood?

In a 1959 interview with Tony Thomas (per "Walt Disney: Conversations"), Walt describes trying to break into the Hollywood industry, and how returning to cartoons was essentially a means to an ends:

"I was a little discouraged with the cartoon at that time — I felt ... that there was no chance to break into [that industry]. So I tried to get a job in Hollywood, working in the picture business so I could learn it. I would have liked to have been a director, or any part of that. It wasn't open, so before I knew it I had my drawing board out, and I started back to the cartoon."

It's safe to assume Walt went to Hollywood looking to make traditional, live-action movies. True, Walt had an "Alice's Wonderland" reel he "trudged around" Los Angeles with (per Gabler), but this was likely less to do with him wanting to show off his aspirations for animation and more because it was the best (and probably only) samples of his live-action directing work he had to show.

Regardless, it failed to impress, probably because of the industry's attitude toward animation at the time (and, admittedly, the quality of the live-action sequences was crude by industry standards). Gabler notes that some of the people Walt contacted suggested he go to New York, but of course, there was no money for that.

Disney was destined for cartoons ... in Hollywood.

Alice's Wonderland

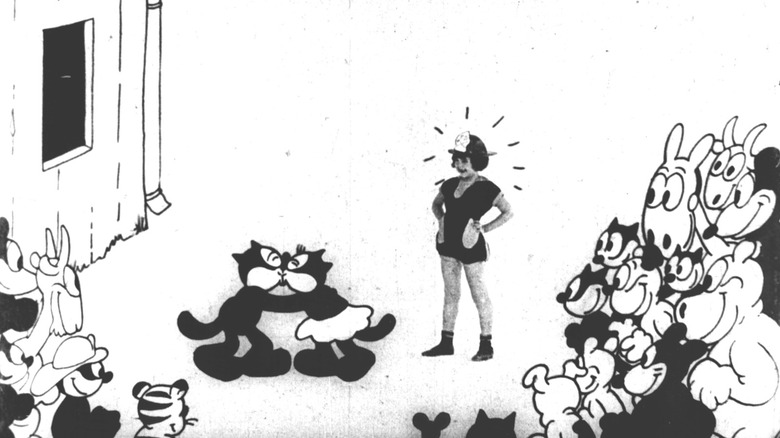

"Alice's Wonderland" was Laugh-O-gram Film's ambitious, and unrealized, animated project inspired by Dave and Max Fleischer's Out of the Inkwell series. Walt's concept was to essentially "invert" what the Fleischers were doing with their Koko the Clown character. Rather than putting an animated character into a live-action scene, he sought to put Alice, played by the young Virgina Davis, into a cartoon world.

Walt Disney was a forward thinker, and it's telling that he would push to innovate within a medium he was a relative newcomer to, with very little resources (or, admittedly, expertise). Luckily, he found a star in young Davis, who would prove key to his later success in Hollywood. Russell Merritt notes in his essay "A Kingdom in Kansas: Walt Disney's Laugh-O-grams," published in the anthology "The Walt Disney Film Archives: The Animated Movies 1921—1968":

Salvation came in the form of four-year-old Virginia Davis ... True, Disney was simply inverting the Fleischer formula ... But the idea revitalized Disney, inspiring his most imaginative and versatile cartoon yet. Little Virginia proved a talented, charming youngster who could play off the cartoon vaudeville with lively dance steps and comic mugging of her own.

Despite "Alice's Wonderland" being compared to the Out of the Inkwell series, there are some noteworthy differences: For starters, Koko the Clown wasn't just any animation — he was the product of Max Fleischer inventing the rotoscope. For the uninitiated, rotoscoping is essentially animation by filming something and then tracing it frame by frame. It's what gives Koko the Clown such a high degree of fluidity and realism. It's a technique that still gets used: Filmation famously relied on rotoscoping athletes for the "He-Man: Masters of the Universe" stock footage. It's also how Industrial Light & Magic did the original lightsaber effect. In trying to do his own version of this, Walt Disney was setting the bar very high.

This fact was not lost on Margaret Winkler.

Margaret Winkler makes a fateful deal

M.J. Winkler Pictures was a distributor of animation, representing Dave and Max Fleischer's Out of the Inkwell series and Pat Sullivan's Felix the Cat series. Winkler had previously expressed interest in working with Laugh-O-gram Films, but Disney was essentially unable to submit anything before his assets were seized, and then had to stall for time (obviously he couldn't just say, "I'm a bit bankrupt at the moment" — not a good look for a potential investor). Likely, her continued interest and willingness to work with this unknown filmmaker, despite numerous red flags like delays and excuses, was motivated by her own desperation: according to Gabler, the Fleischers were threatening to take their popular Koko the Clown elsewhere, and Pat Sullivan was infamously difficult to work with (he was also not a great human being in general). Either way, she wanted to move fast, wanting a new print by the end of the calendar year.

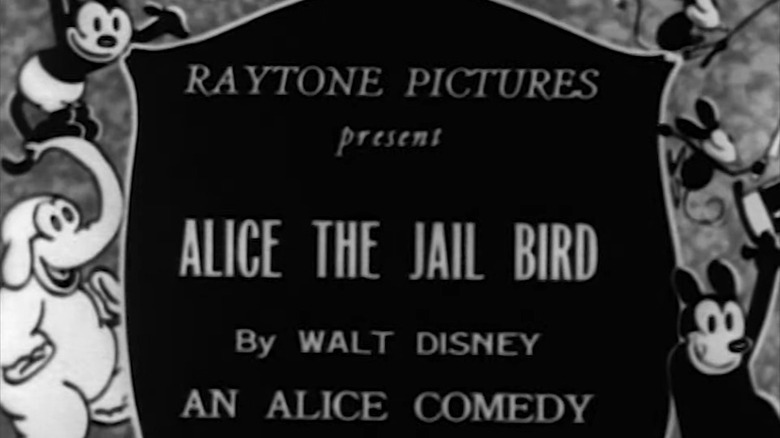

The original "Alice's Wonderland" film was, admittedly, rough. Disney himself had completed the animation alone since there was no more pay (or studio) for hired artists. The live-action sequences also required work. Winkler agreed to option the series on October 15 — ordering 12 films in that initial contract — but stipulated that the photography of Alice needed to be improved. She also was firm that Virginia Davis had to reprise the leading role. Likely as a show of good faith, she (generously) agreed to pay upon receipt per film, which put Disney in a much better position than he had been previously with Laugh-O-grams and Pictorial Clubs of Tennessee. He now had a new problem, however: unemployed in Hollywood, living with family members and subsisting on borrowed money, Walt Disney had to somehow found an animation studio.

Roy Disney comes to the rescue

Roy O. Disney — eight years Walt's senior — was always looking after his baby brother. This dynamic started very early on in their relationship. As a youngster, Roy pushed Walt in a baby carriage up and down Chicago streets — he even bought his little brother toys from his own (no doubt meager) funds. In Kansas City, Roy paid the $15 bond required for his brother to start a job with the railroad. After Walt returned home from the Red Cross following the war, Roy helped him land his first professional artist job with the Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio. Then, despite being on disability and recovering in a veterans' hospital, Roy lent Walt the money he needed to pay room and board in Los Angeles.

So, when Walt was faced with the challenge of opening an animation studio with no resources, few connections, and very little time, there was one natural person for him to turn to: his faithful, reliable older brother, Roy.

As the story goes, upon receiving word from Winkler that she would order a series of Alice cartoons, an exuberant Walt headed to the veterans' hospital to share the good news (a little too excitedly — apparently Walt disturbed the nearby recovering vets). Walt pleaded for his brother's help, "Let's go, Roy!" Roy, after calmly asking questions to make sure the deal was profitable, agreed, saying, "Okay, Walt, let's go."

The following morning, Roy, who had struggled with TB for years, walked out of the veteran's hospital, never to relapse again.

Roy would go on to outlive his brother by five years, reaching the ripe old age of 78. He lived long enough to personally oversee the opening of his brother's passion project (which Roy had renamed Walt Disney World in his late brother's honor) and died shortly thereafter, just days before the anniversary of Walt's death, on December 20, 1971.

It's obvious what Walt got out of their partnership — startup money, business expertise, etc. — but I think it's clear that Roy Disney benefitted too.

The birth of Disney Brothers Studio

The next step for Walt and Roy was to acquire startup funding. Even with Walt doing all the writing, directing, cinematography, and animation himself, there were certain unavoidable costs to producing the first Alice Comedy for Winkler. Walt needed to acquire equipment, he needed to retain Virginia Davis (who was back in Kansas City — or so he thought), and he needed to rent space. Roy had $200 saved up to contribute, but obviously, they would need a lot more. And unfortunately, Walt had already burned some bridges with the Laugh-O-grams Films' insolvency (this actually would get sorted out down the line, but the bankruptcy proceedings were still in the early stages at this time).

Roy, always prudent and professional, first tried acquiring a loan from banks; however, he was turned down because the cartoon business was not seen as viable — a reoccurring problem for Walt. The next best option was to ask for small loans from virtually all their family and friends. It took some time, but they did manage to scrape together startup capital. To save on expenses, Roy and Walt even moved into a cheap apartment together and kept food costs low by splitting meals.

Interestingly, Gabler suggests that it was never Roy's intention to actually go into business with Walt, but rather just help his younger brother get his new venture set up:

It had never been Roy's intention to join the enterprise ... But Roy could never resist his younger brother. He claimed that Walt, who was so enthusiastic and innocent-seeming, "would win your heart, and you wanted to help him, really," and he admitted that he was afraid that without his protection ... Walt would have been taken advantage of. To prevent that, Roy, professing a "love of Walt," agreed to become Walt's manager and guardian angel in business as he had been in Walt's life.

The hard work soon paid off, and Walt did manage to complete the first "Alice" short ahead of schedule. It was not great — but Winkler paid for it, as she promised she would. By February, the two had earned enough to move the first floor of a building, which featured the studio's name embossed in gold on the front window for all to see: the "Disney Bros." had arrived.

For a time, the Alice Comedies kept the studio going — but to stay in the game, they would need more than the few, passable animated shorts done almost completely by one person. They needed a team. They needed a hit. They needed an icon.

And in 1927, a full year before "Steamboat Willie" his theaters, Walt found one.

Join us next week for 100 Years of Disney Magic Part 3: The Breakthrough Success of Oswald The Lucky Rabbit.