Knock At The Cabin Ending Explained: Judgement Call

This post contains major spoilers for both "Knock at the Cabin" and its source novel, "The Cabin at the End of the World," below.

The Biblical concept of Judgment Day carries with it a number of ethical, social, and psychological quandaries. Setting aside any belief in a literal return of a messianic figure who will pass judgment on humanity, the idea alone has connections to everything from the moral concept of sin to the legal concept of law and order to something as individual and every day as a report card or performance review.

The idea of Judgement Day can be boiled down to that of a final exam. Since such a test would take an eternity in order to weigh all the nuances involved, the quickest way for humans to conceive of it boils down to optimism or pessimism: are people basically good or basically evil? Can in-between answers exist? On whose shoulders can humanity survive, if it's to survive at all?

M. Night Shyamalan's latest film, "Knock at the Cabin," tackles these philosophical and spiritual topics in a far more secular fashion, filtering them through the lens of genre. Despite that, it's still very much a Bible story writ large, a harrowing, compelling, and moving parable about the power of humanity's capacity for love in the face of dark times and its potential to change — if not save — the fate of the species.

Even if you're a-rocking, the end comes a-knocking

Like all the best parables, "Knock at the Cabin" tackles the macrocosm of the apocalypse by presenting a story in a microcosm. Adapting the premise of Paul Tremblay's novel "The Cabin at the End of the World," Shyamalan and co-screenwriters Steve Desmond and Michael Sherman keep the events of the film largely confined to a single location, a remote cabin located somewhere in the Pennsylvanian woods. Married couple Andrew (Ben Aldridge) and Eric (Jonathan Groff), along with their daughter Wen (Kristen Cui), have decided to vacation in what appears to be a bucolic, secluded spot.

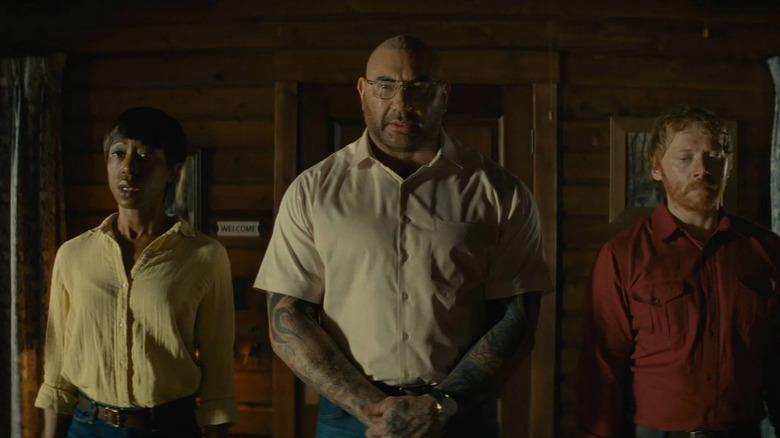

However, emerging from the woods one afternoon is a gentle, soft-spoken giant of a man, a schoolteacher named Leonard (Dave Bautista), who approaches Wen and admires her grasshopper collection. After attempting to gain Wen's trust, Leonard's companions arrive: a nurse named Sabrina (Nikki Amuka-Bird), a chef named Adriane (Abby Quinn), and a gas worker named Redmond (Rupert Grint). All carry ominous, homemade weapons, and advance on the cabin. Wen attempts to warn her fathers of the danger, and despite the couple refusing to allow the group's entry upon knocking, the group invades the cabin by force as the family discovers all communication with the outside world has been cut off.

The group ties the parents to chairs, explaining that they're the victims of a specific, shared vision of the end of humanity and that these visions have led them to the cabin where they are to continually request that Eric, Andrew, and Wen must make a sacrifice of one of their own lest the apocalypse comes to pass. The group's sudden arrival, along with their insistence that the family has been chosen at random, is analogous to the unfair inconvenience of life's many obstacles.

The specter of hate, zealotry, and insanity

The progressive mind tends to be skeptical of faith, especially considering the long history of religious beliefs weaponized for ulterior motives. Andrew and Eric find Leonard's claims that a mandated sacrifice has anything to do with an impending apocalypse dubious at best, even after the group ritualistically murders Redmond, who dons a cloth on his head and intones that "Part of humanity has been judged." Andrew, a cynical lawyer, recognizes Redmond after his death as a man named O'Bannon, a bigot who attacked him in a bar years ago before going to jail for the assault. He also observes the way Leonard continually checks his watch, turning on the cabin's television at the precise time that certain pre-recorded news broadcasts supposedly reveal the apocalyptic effects of the family refusing to make a sacrifice. Even Eric, who suffered a concussion during the group's invasion which is making him more suggestible, finds the fact that the group found each other on an online message board highly suspect.

The rational explanation for why these people have attacked and held the family hostage is prejudice, regardless of intent. Through flashbacks, it's revealed that Andrew and Eric have a long history of dealing with such closed minds, from Andrew's parents looking down on his relationship to having to lie to authorities in order to adopt Wen. Shyamalan wants the specter of such hate, as well as Leonard and the group's potential insanity, to hang over the film so that enough reasonable doubt exists. Real-life recent events like QAnon devotees storming the Capitol and historical instances of cults like Heaven's Gate are brought to mind. There is also a greater doubt: whether humanity deserves to survive at all, a sentiment that Andrew vocalizes at one point.

Shyamalan's twists on genre — and himself

"Knock at the Cabin" belongs to a long tradition of speculative fiction that uses apocalyptic events as a backdrop. While the examples are too numerous to fully include here, "Knock" is particularly close to the works of Rod Serling on various episodes of "The Twilight Zone," the Richard Kelly film (itself an adaptation from "Zone" contributor Richard Matheson) "The Box," the faith vs. reason debates as seen in the Damon Lindelof-produced shows "Lost" and "The Leftovers," and even the faith-based argument for optimism in a cynical world of "The Exorcist."

Shyamalan embraces such comparisons given his love of and adept knack for genre. Boiled down to its core elements, "Knock at the Cabin" is a home invasion thriller (Eric even says "It wasn't a home invasion" near the end, the line a playful fourth-wall-breaking-wink) with apocalypse and disaster movie overtones. With the ambiguous nature of Leonard and the group's faith — they never claim to be receiving visions from any particular god — the film even brushes up against folk horror, the group's spirituality leaning a little toward the occult.

Shyamalan cleverly entwines these genres and their various tropes (the better to manipulate and twist them, of course), while clearly acknowledging his own penchant as a filmmaker for third-act narrative twists. Shyamalan plays a wicked meta game with his audience as well as his characters. To wit, Andrew and Eric are as desperately trying to discern the truth of what's going on as the audience is, with Andrew compiling evidence and doling out theories that could herald a wacky twist ending, a la Shyamalan's "Signs," "The Village," or even his prior film, "Old." This technique only increases the tension, allowing the director to double down on what makes a good thriller tick.

The man comes around

As Andrew, Eric, and Wen struggle to break free, the group continue to murder each other one by one while claiming that the mounting tragedies occurring around the world (earthquakes, tidal waves, a new pandemic, and passenger airplanes suddenly dropping from the skies) are the direct result of a failure to make a sacrifice. To Eric, it becomes clear that these events are not a misdirect, an illusion, or a manipulation, as he sees the skies darken upon Leonard's suicide and fixates on the man's warning that the family only has minutes to make their choice after his death before the apocalypse is irreversible.

Eric tells Andrew that, during Redmond/O'Bannon's murder, he saw a mysterious figure in the mirror behind the man, explaining how this has led him to believe larger forces are at work. Although he does not share his belief, Andrew accepts Eric's belief, and the two move closer to each other while Andrew brandishes the gun he had bought in order to protect his family and himself from hatred.

Eric explains how he believes that the foursome who knocked at the cabin was actually the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Yet rather than representing humanity's doom, they represented humanity's virtues: penitence, nurturing, healing, and guidance. Eric believes that the family was meant to witness their deaths, to feel their loss as a way of activating their altruism. Telling his husband that he is at peace and describing a vision he's had of an older, happy Wen going to dinner with Andrew, Eric insists he is sacrificed. Wen, safe in a nearby treehouse from the increasingly violent lightning storm, hears a gunshot ring out. Eric is dead.

The mystery of faith

Shyamalan doesn't show us the exact circumstances of Eric's death, with the shot occurring off-screen. Given the blocking of the moment before, it's entirely possible that Eric shot himself (with suicide supposedly not being accepted as an apocalypse-averting sacrifice) or that the gun went off by accident due to Andrew's stress.

Emotionally devastated and wounded but alive, Andrew takes Wen to Leonard's truck, their own car having been damaged by the group earlier. There, Andrew discovers proof that the foursome all really were who they said they were: average, everyday people. Driving down the road, Andrew and Wen come upon a diner where people have been riding out the storms. Inside, several live news broadcasts describe how the pandemic is being controlled, passenger planes have stopped falling from the skies, and a number of survivors are being rescued after the quakes and tidal waves. Returning to the car, Andrew and Wen silently observe that Eric's favorite song, KC and The Sunshine Band's "Boogie Shoes," is playing on the radio.

As Shyamalan explains in the film's official press kit: "I subscribe to this type of storytelling where you count on the incompleteness of it, where you don't fill in everything and you let the audience do the dance with you. Think of 'The Twilight Zone,' where that conjuring of your imagination is required to finish the painting." With the film's ending, it's clear that Shyamalan isn't interested in providing a rigidly-defined finale: was the subsiding of the apocalyptic events a divine judgment thanks to the family's sacrifice, or mere coincidence? Is "Boogie Shoes" a message from Eric from the afterlife, or just a popular oldie playing over the airwaves? "Knock at the Cabin," like all great mystery stories, is more interested in the questions than the answers.

Differences from the book

That being said, the changes made by M. Night Shyamalan and his co-writers for the movie in adapting the book make the film's message that much clearer. In Paul Tremblay's novel, Wen is killed by accident during a scuffle, and once Leonard is dead, Andrew and Eric decide not to make a further sacrifice after being told that Wen's accidental demise doesn't count, believing that a higher power who would require more suffering of them shouldn't be appeased.

In the film, Sabrina is the one accidentally killed, shot by Andrew in self-defense. This increases Andrew's moral guilt as well as makes the group hew closer to victims themselves rather than just victimizers. Additionally, Eric's death may also have been accidental, calling into question the supposed "sacrifice" of the family.

Judge not, lest ye be judged

Whether the group was right or wrong, whether or not the events have all been one big test, with an unseen power observing humans in the same way Wen observes and records the behavior of her grasshoppers — it isn't the point of the film. It's that tragedies happen — unexpectedly, unfairly, and, unlike Leonard's knock, unannounced — and that we must find the rationale and judgment for ourselves.

In any case, it's the kindest and warmest of us, the ones who willingly sacrifice their time and energy, the unfairly burdened and persecuted, who point the way toward humanity's survival, who bear the brunt of our sins while giving us hope for the future. Unlike the book's pessimism, "Knock at the Cabin" takes a bittersweetly optimistic approach to the material. As Shyamalan explained in the press kit, "It's a modern-day biblical story ... The film is reflective of my current feeling that everything that's going on in the world doesn't look good and doesn't feel good, but I do feel we are struggling together in the right direction ... we deserve a chance to continue." It may be a sign of divinity or it may merely be a fiction to comfort us in dark times, but perhaps everything happens for a reason, and perhaps we all may be fairly judged in the end.