How Walt Disney's First Cartoons Drove Him To Bankruptcy

Welcome to 100 Years of Disney Magic, a series examining the history, achievements, and legacy of Disney Studios over the last century.

The Walt Disney company is now a centenarian. First founded as the Disney Bros. Studios in October 1923 — a partnership between Walt and his older brother Roy — the animation company would go on to change the media landscape in ways that would have shocked even the forward-looking, ever-ambitious Uncle Walt himself.

The studio is a cultural behemoth, thanks to its years of box office dominance, cross-media strategy, and massive library of highly valued IPs. Disney was the first studio to have two billion-dollar movies in one calendar year in 2010, and then was to have a total gross of $3 billion at the domestic box office in 2016. After buying up Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm, the company officially acquired the juggernaut 21st Century Fox, a studio with roots going all the way back to the birth of the motion picture industry. The $71.3 billion deal was unlike anything we've ever seen before.

Whether you're a Disney Adult, a True Believer, or a Jedi, chances are there is something under the studio's banner that is close to your heart. And your wallet: Disney reported in 2022 record revenues for "Parks, Experiences and Products segment." Billions and billions of dollars earned through theme parks, cruise ships, and licensing deals. Money talks, and this cashflow is saying "we love Disney."

And it all started, not under the gleaming spot lights of Hollywood glamour, nor the hustle-and-bustle of a busy metropolitan center like New York City or Chicago — but in the dry, midwestern urban center of Kansas City, Missouri.

Walt Disney: A man of dreams

We can't readily talk about the history of The Walt Disney Company without first talking about its namesake.

Walter Elias Disney was a man who beat the odds. He came from humble beginnings, and was not particularly remarkable. He showed an interest and aptitude for illustration at an early age, and was known for a boyish playfulness, but he was not especially brilliant, creative, or enterprising. Young Walt just wanted to be a cartoonist — and avoid the life of misery and failure he witnessed in his father, Elias.

The seminal biography "Walt Disney: An American Original," penned by long-time reporter Bob Thomas (a Hollywood icon in his own right), asks,

How could it happen? How could one man produce so much entertainment that enthralled billions of human beings in every part of the world? That is the riddle of Walt Disney's life. ... It seems incredible that the unschooled cartoonist from Kansas City, a bankrupt in his first movie venture, could have produced works of unmatched imagination.

Yet, this common, unremarkable quality is a key element to his appeal as a public figure. Uncle Walt, as he would come to be known, was more than just an artist or even a visionary. He would become a true American icon — a portrait of the American dream, realized. Neal Gabler describes this phenomenon in "Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination." "An American Everyman," Walt Disney was the embodiment of 20th-century American ideals: an unassuming, salt-of-the-Earth family man and entrepreneur who clawed his way from poverty and anonymity to immense wealth and influence.

So much of the Disney brand today is still tied to Walt's journey from obscurity to exceptional. Optimistic to a fault, and distinctly American.

Marceline, Missouri: An impossible ideal

Walter Elias Disney was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1901. The fourth child of god-fearing parents Elias and Flora Disney, he stayed in the big city for a short time. It was his next home, a farm in Marceline, Missouri, that would have a profound, unforeseen effect on his personality, values, and destiny.

The Disneys joined the small, rural community in 1906, moving into a humble home on a picturesque farm. Upon arrival, young Walt was taken aback by the idyllic charm — lush, green fields complete with dreamy weeping willow trees. The town itself featured sturdy buildings and a tight-knit community that — coming from Chicago — must have felt like one big extended family. The effect was, as Gabler puts it, "enchanting."

The pastoral charm of life on a midwestern farm was powerful during Walt's formative years, and its influence can be seen on his never-ending pursuit to celebrate the American Ideal — which, whether it be in his films or theme parks, often is rooted in the small-town, rural communities of yesterday. This can be seen in his movies, his hobbies, and the concepts for his original theme park, Disneyland. Gabler argues:

It was as if Marceline were a template for how life was supposed to be, and he were trying to re-create the town, no doubt attempting in the process to recapture its sense of well-being, freedom, and community, essentially recapturing what he would call the most blessed passage of his childhood. Marceline would always be a touchstone of the things and values he held dear; everything from his fascination with trains and animals to his love of drawing to his insistence on community harked back to the years he spent there.

Walt's affection for Marceline was self-aware. He reflected on this period of his life fondly, and associated it with when he discovered a love of drawing. Walt would spend his later years honoring it. According to Thomas, Walt built an exact replica of the Marceline barn on his California estate. Disney returned to the small town in 1960 to have a school named after him. It was not Walt's birthplace, nor was it where he spent most of his childhood. But Marceline, in his heart, was home.

Walt Disney's first big break

Having fallen on hard times (sadly, a regular theme throughout Elias Disney's life), the family moved to Kansas City in 1910, where Walt would remain until he relocated to Los Angeles, California, in 1923. Life was much harder in the city; gone was the wildlife, livestock, and scenic beauty, replaced with the harsh reality of responsibility and hardship. The Disney children were recruited by their father to deliver papers, which was gruelling work — especially in the harsh, midwestern winters. At least Walt had his older brother Roy, eight years his senior, looking out for him. The two shared a special bond, with Roy being a pragmatic mentor of sorts who clearly had a special affection for his baby brother.

Walt's first real escape came when he was just 17. After a stint with the Red Cross Ambulance Corps at the tail end of the Great War, he spent some time in France before returning to Kansas City, where — after turning to Roy for advice — he landed a short-lived art gig apprenticing for professional artists Louis Pesmen and William Rubin (Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio). The job mainly involved art work for advertisements and catalogs. Still, it was drawing professionally for a living, and the young Disney was ecstatic to be one step closer to his cartoonist dreams. Unfortunately, his employment would only last a mere six weeks, but it did result in a fateful introduction: Ubbe Iwerks.

(If that name sounds familiar, it's probably because Iwerks was the "father" of Mickey Mouse — but that's a subject for a later date.)

After the two artists were laid off, Iwerks (who later shortened his name to Ub Iwerks) and Disney teamed up to create their own art studio, Iwerks-Disney (because "Disney-Iwerks" sounded too much like an optometry business). This too was short-lived, but in this case, it was because better opportunities came along.

'Cartoons that moved'

Disney landed a job with a slide company, Kansas City Film Ad Company, which introduced the young illustrator to the relatively new art of filmmaking. As Thomas writes in his biography, Walt Disney did not seek out animation — the business of "cartoons that moved" found him. Originally, the plan was for Disney to take on the cartoonist job with Film Ad to help supplement his venture with Iwerks; however, once he got a taste of animation, he was hooked. He would even turn down the dream offer of being a cartoonist for the Kansas City Journal because he was enjoying this new line of work so much. Film Ad produced one-minute animated advertisements that aired before motion pictures. The position offered Disney an opportunity to learn about animation and basic live-action filmmaking, while also honing his own, mostly self-taught, skills as an artist.

Disney saw the potential in the medium and showed great aptitude for it. The Kansas City studio was using an admittedly primitive form of animation that involved photographing paper cutouts, but by studying E.G. Lutz's "Animated Cartoons" as well as Eadweard Muybridge's groundbreaking motion studies series, Disney was able to at least improve the realism of the art. The young man was so intrigued by the medium that he convinced his boss, A. Vern Cauger, to lend him a camera so he could experiment after work hours in a studio Walt pieced together in a garage.

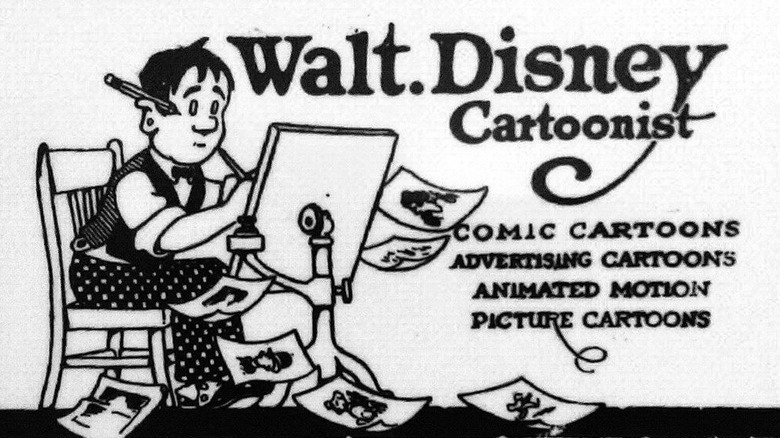

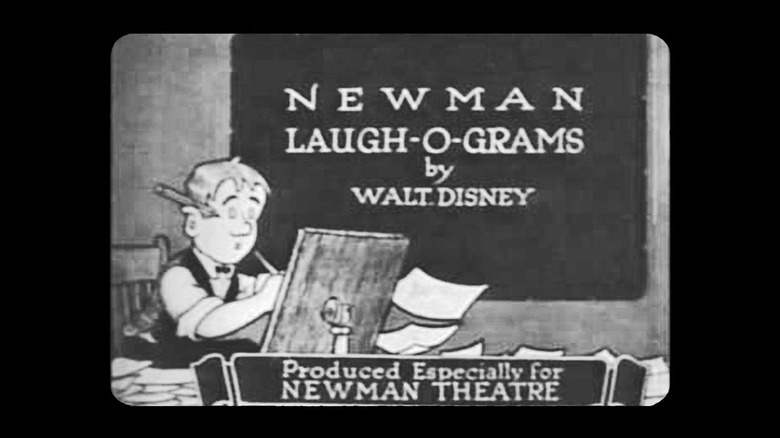

Disney created his own humorous shorts wherein his hand "drew" a comic gag at very rapid speed. (This is a common theme in early animation history, when the medium was stuck on the idea of animations being rooted in drawings — as seen with "The Enchanted Drawing" in 1900 and "Gertie the Dinosaur" in 1914). Disney took his new shorts to the Newman Theater Company and sold them, — though, unfortunately, not for much money because Disney forgot to calculate a profit margin. Regardless, this marked the beginning of Disney's first animation studio venture: the Newman Laugh-O-grams.

Laugh-O-grams

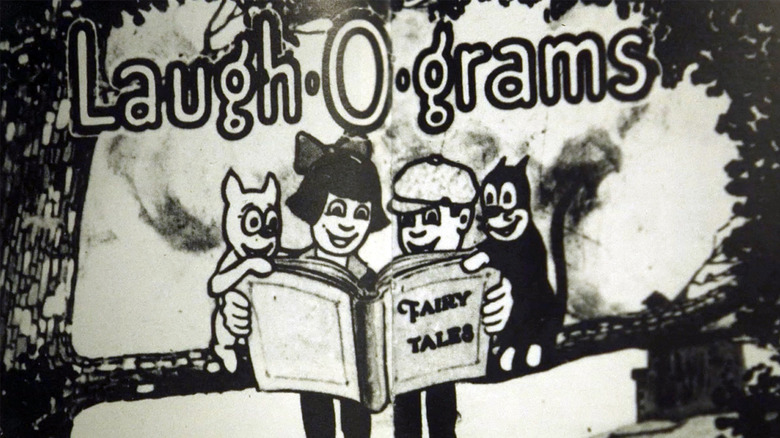

The Laugh-O-grams venture showed promise — enough for Walt Disney to sink his savings into his new studio, alongside several investors. Disney was able to rent space and hire several young men (paying as little as possible) to help with the animation work. What started as topical fast sketches morphed into satirical retellings of fairytales like "Puss in Boots" and "Little Red Riding Hood." Eventually, taking inspiration from Max Fleischer's "Out of the Inkwell" animations, Walt would embark on an "Alice in Wonderland" project featuring a live-action girl interacting with a cartoon world. (It's a bit like a very basic version of the animated sequences in later Disney movies like "The Three Caballeros," "Mary Poppins," and "Bedknobs and Broomsticks.")

In "A Kingdom in Kansas: Walt Disney's Laugh-O-grams," published in the collection "The Walt Disney Film Archives: The Animated Movies 1921—1968," Russell Merritt notes that these Laugh-O-grams — although they never became popular or successful — are invaluable historical texts that reflect Walt Disney's personal creative journey. In these animations, Merritt sees the beginning of what would become the staple Disney Brothers style a few years later:

The Laugh-O-grams are silent movies born to swing. From the start, Disney conceives his cartoons as a form of visual novelty jazz, filled with mock concerts and dance routines. Many of them amount to silent musicals, a foretaste of the syncopated Mickey and the jazz-mad Silly Symphonies.

Despite the artistry on display, financial problems plagued Disney in his Laugh-O-grams venture. He was confident in success, but ultimately ignorant of the market. Cartoons at this time weren't seen as something that drew customers, so distributors wouldn't invest in them. After struggling to get distribution, Walt accepted a bad deal with Pictorial Clubs of Tennessee (Merritt characterizes it as "a fly-by-night company"), which resulted in work for a $11,100 project being done on a mere $100 deposit and the promise of a later payout that didn't materialize. Eventually, Pictorial would be forced to honor the deal, but by that time, Laugh-O-grams was long defunct.

The end of Laugh-O-grams

Ultimately, Laugh-O-grams died a prolonged but steady death over its short existence. Walt did his best to keep the enterprise alive by cutting expenses, laying people off, and even skipping meals — but other than the occasional influx of cash from investors, Disney was never really able to make any money. Remember, his Newman deal was at cost, so even when he was selling pictures for the local theaters, he wasn't turning a profit. He desperately needed a proper distribution deal that would take his animations outside of the immediate area, and although one New York prospect was a solid lead, Disney just didn't have the resources or time to make it happen. By the summer of 1923, Walt Disney had to admit defeat: With the money gone, investment channels exhausted, and no real new prospects, the ambitious young man had no choice but to close up shop. For someone like Walt, who was so confident in his endeavors and knew of his own potential, this must have been a major blow.

Walt's decision to declare bankruptcy was likely influenced by the artist's isolation at the time. His family had moved away from the area. Roy, who looked out for Walt's wellbeing essentially his entire life, had relocated to California in order to recover from tuberculosis, while the rest of the family basically left for greener pastures by November 1921. Disney scholars largely see Walt's attitude towards building up his Laugh-O-gram "family" as a way to cope with loneliness. With no money to pay animators, Disney was effectively on his own.

On the advice of his family, Walt decided it was time to leave Kansas City (leaving poor Iwerks to sort out the bankruptcy petition). After raising ticket fare by going door-to-door selling photography services, he headed to Los Angeles. He had almost nothing to his name, short of some drawing materials, a small sum of cash, bagged lunches, threadbare clothing, new shoes, and a used suit gifted to him from a family friend — all packed in a cardboard suitcase.

Yet, he headed to Hollywood with a newfound determination to succeed. And as we all know now, that optimism was not misplaced.

Join us next week for 100 Years of Disney Magic Part 2: The Birth of Disney Brothers Studio.