Jokes Were Never The Top Priority When It Came To Writing King Of The Hill

"King of the Hill" was always an odd duck. Its predecessor, the legendary animated series "The Simpsons," earned its acclaim by being endlessly inventive and funny. "South Park," which also premiered in 1997 like "King of the Hill," weaponized its crude animation and gross-out humor to make a big impression. Fans of "The Simpsons" venerate specific quotes and visual gags as if they were holy relics, while fans of "South Park" still remember certain episodes that shocked them. The folks behind "The King of the Hill" weren't especially interested in that stuff. "There were definitely some writers ... pulling it more in the gag direction. My strength is more observational stuff," series co-creator Mike Judge told IGN in a 2006 interview. "King of the Hill" could be funny, but Judge cared more about authenticity. The result was a TV series committed to capturing the lives and mannerisms of working-class folks in Texas — like protagonist Hank Hill.

The manual of "King of the Hill Dos and Donts," used to instruct the show's animators, is especially revealing. "No looking into the camera," reads one. "No high-fives!" reads another. "John Wayne wouldn't do it, neither would Hank." Unlike other animated comedies, the cast of "King of the Hill" never breaks the fourth wall and only rarely references contemporary pop culture. When they act out or do something unexpected, everybody else notices. As a result, "King of the Hill" is less flexible than "The Simpsons." But that also allowed the cast and crew to be more specific. The show is set in Arlen, Texas, and that means something.

An authentic world

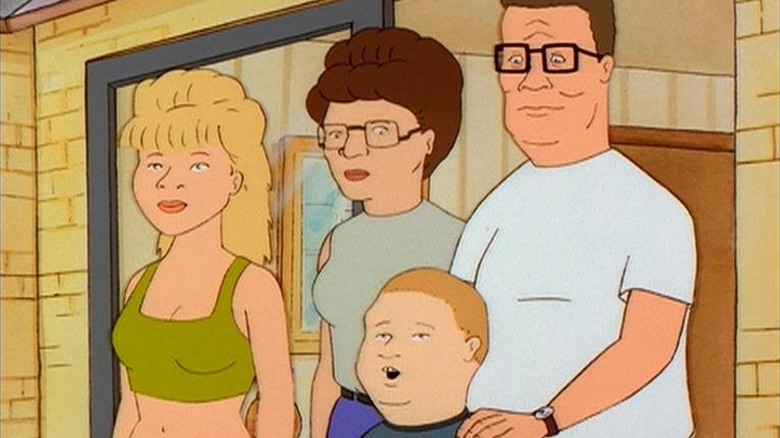

Let's dig into the characterization first. Compare Hank Hill to Homer Simpson. Homer can be a good or bad father, an everyman or a folk hero, depending on the needs of the writers. He can swing from strangling his son Bart with his bare hands to being a confused but earnest parent to his daughter Lisa — all without breaking the reality of the show. Hank is trickier. He works as an archetype, the only sane man in a swiftly changing world. But his behaviors are all rooted in his past experiences. His father Cotton gave him a complex about his masculinity, which he's spent his entire life trying to compensate for. He can't understand why his son Bobby has different interests than he does or why his niece Luanne is much less prudish than he is. No matter what context he is put into, his psychology remains consistent.

Cotton and Luanne were invented by the show's co-creator Greg Daniels to clarify Hank's psychology to the audience and to push him out of his comfort zone. The "King of the Hill" producers recruited Daniels to transform Mike Judge's original pitch into something more accessible. Judge was happy enough with what Daniels brought to the show that he offered him a co-creator credit. Daniels insists Judge's genius was there from the initial pitch. "It had this authentic world I hadn't seen on TV," he says in the documentary "Making of King of the Hill." While "The Simpsons" might have pushed the boundaries of what "normal" families looked like on television, Judge, Daniels, and company went even further to ensure that the characters of "King of the Hill" were "based on real life and observing great details in people."

Against the Harvard Lampoon

The emphasis on realism also meant that Arden could not be a stand-in for every town in the United States. It had to just be Arden, Texas. The scale of a typical "King of the Hill" episode is small. The characters talk like people from their economic and social backgrounds instead of 'comedy characters.' Per Los Angeles Times, Mike Judge insisted that the show's writing room had a share of Texans alongside folks from the Harvard Lampoon (of which Greg Daniels was one.) Judge didn't want a team of writers busy "trying to get each other's references." As part of this commitment, the "King of the Hill" staff went on research trips to Texas during production to find ideas for their show. Some of the show's most memorable details, like plastic heads used in beauty school, came directly from these trips.

"King of the Hill" rarely attempted parody episodes like "The Simpsons" classic "Homer at the Bat." But it could pull off episodes like "Hilloween." In it, a religious woman named Junie Harper convinces Luanne and Bobby that Halloween is a holiday for Satanists. Fearing for Bobby's soul, Luanne takes him to Junie's "Hallelujah House." In response, Hank defies a curfew — it's a long story — to trick or treat across town and bring Bobby back. He does so wearing his childhood devil costume, which is obviously too small for him. Another series might play up Hank tearing through his costume or render his impassioned march a parody. Not "King of the Hill." Hank never once breaks character in his quest to retrieve Bobby. When Luanne runs out to join him in a skimpy devil costume, their reconciliation is played sincerely. Nobody looks at the screen once to say, "Well, that just happened."

All in the family

Why animation, then? While "King of the Hill" aspired for realism, "realistic" animation is incredibly difficult, time-consuming, and expensive to produce. The series might have worked even better as a live-action sitcom. (A live-action spin-off special was on the cards once.) Personally, though, I think that Mike Judge has always been an animator at heart. With "King of the Hill," Judge's ambition wasn't just to tell funny and entertaining stories but to create a believable world from scratch. Every detail, be it the characters' designs, behaviors, or local hang-outs, was fussed over. The result is not necessarily as iconic as "The Simpsons," or as bracing as "South Park." But it has its devoted fans.

The worldview and setting of "King of the Hill" are so fully formed that there's not much to explain to curious audiences. If you understand where the characters are coming from, you get it. Episodes like "Hilloween" have details specific to the U.S. like culture wars fought over seemingly innocuous holidays. Yet the core of the story, of Hank trying to understand his relatives, is understandable to anyone who's struggled with conservative older parents or rebellious children. The show might seem like a time capsule today, more reflective of Judge's vision of middle (white) America in the 1990s than what it actually was then. But I respect its dedication to grounding its humor in the characters, taking their feelings seriously, and never selling their world short for a joke.