Othello Was A 'Maddening' Film For Orson Welles To Make

William Shakespeare's "The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice," inspired by the Italian story "Un Capitano Moro" by Cinthio (1504 – 1573), was likely first performed around 1603 at the Globe Theater just outside of London. The story follows the titular Venetian military commander and his relationship with Desdemona, the daughter of a senator. Othello and Desdemona are both mature adults, and speak their emotions clearly, unlike Shakespeare's other well-known Veronan youths. One of Othello's ensigns, Iago, announces to the audience that he secretly hates Othello, and aches for his undoing. The term "Moor" is an old English word used, insensitively, to refer to anyone with dark skin, and didn't necessarily refer to any country of origin. The word is fraught and deserves more context than I can provide here.

Because Othello's race is constantly mentioned in the text of the play, many critics see Iago's hate and jealousy of Othello to be motivated by brazen racism. Iago sets about a plot to make it look like Desdemona is actually having an affair with another one of Othello's officers, a chump named Cassio. The jealousy drives Othello to violence, and he eventually kills Desdemona. Then, learning about Iago's lies, he ends his own life, as well. Spoilers on a 420-year-old play. "Othello" is an intense, grand tragedy.

For many years, thanks to widespread institutionalized racism throughout Europe and the United States, Othello was typically played by white actors who darkened their skin on stage. It wouldn't be until 1825 that actor Ira Aldridge would become the first Black actor to play the part. Look up the multi-volume biographies about Aldridge sometime, as he led a fascinating life.

The first signs of trouble

White actors continued to play the role on screen for over 170 additional years, however. White actors playing Black characters was widely accepted and quite common for many decades, as there were times and places where Black actors were not permitted to perform. White Othellos became a stubborn, racist acting tradition. Along the way, actors like Laurence Olivier, Orson Welles, Anthony Hopkins, and Michael Gambon have played Othello. The first Black actor to play Othello in a major cinema adaptation was Laurence Fishburne ... in 1995. Patrick Stewart also played Othello in 1997, but in that production, all the other characters were played by Black actors.

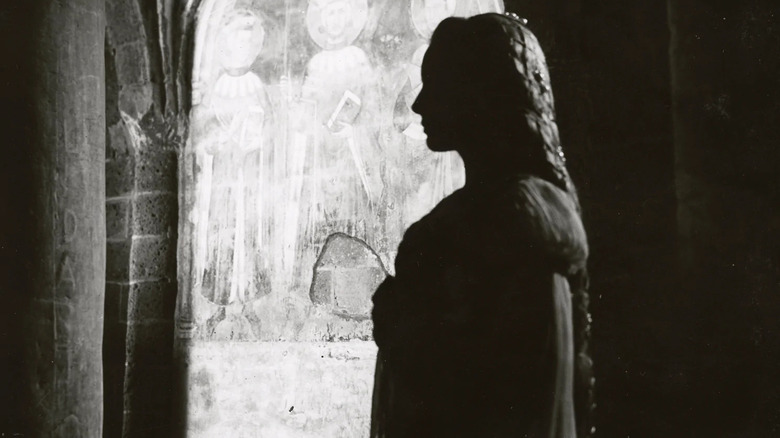

Welles adapted "Othello" to film in 1951, writing the script, directing, and playing the title character himself. Suzanne Cloutier played Desdemona, and Irish actor Micheál Mac Liammóir played Iago. Welles has notoriously had trouble on his film adaptations, and his "Othello" was perhaps one of the more chaotic. Welles' production of "Othello" was detailed in the 1992 book "This is Orson Welles," which was a series of transcribed conversations between the filmmaker and Peter Bogdanovich.

Bogdanovich knew that "Othello" took a notoriously long time to make, having begun its filming as early as 1949, prior to the making of "The Third Man." Welles tells Bogdanovich that all the funding was secured via Scalera Film Studios. Importantly, he experienced no studio interference, something Welles was all too familiar with.

Get everyone naked

Welles assembled a cast and traveled to his shooting location when he ran into the first bump in production. Then the second, larger bump. Welles explained, saying:

"I gathered together my actors and [Alexandre] Trauner [art director] and my Italian crew, and away we went to Mogador to shoot it. We arrived in this condemned area — a little-known, out-of-the-way port on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, and everybody checked into hotels. Two days later, we got a telegram saying the costumes wouldn't be coming because they hadn't been completed. A day later, a telegram came saying they hadn't been started. And then a telegram came saying that Scalera had gone bankrupt. So I had a company of fifty people in North Africa and no money ... but how can you shoot 'Othello' without costumes?"

Welles had a brilliant idea as to how to shoot a period film without costumes: get everyone naked. Or, at the very least, shoot multiple key scenes in a Turkish bathhouse, where the men would be in nothing but robes and towels. As they were shooting, local tailors were hired to cobble together what costumes they could. While the Turkish bath scenes add an element of intimacy and privacy to his "Othello," they were in fact born entirely of production necessity. Welles revealed that his ideal costumes would have been derived from particular Christian art — dressing politicians in animal-like outfits — and were meant to expose a certain degree of hypocrisy in the Italian Catholic court. With local tailors, that wouldn't be possible anymore.

"I shot until the money ran out," Welles said. This was all being done with his own personal cash, by the way. After that, Welles essentially began having to pass the hat, asking new investors to chip in a few bucks.

He found one ... and he wanted to be in the movie.

Passing the hat

"[E]verybody had to go home until I could earn some more or find some more," Welles said. He continued, saying:

"In fact, we stayed a little longer by virtue of a fellow who arrived and arranged for sales of the film for some strange countries like the Dutch East Indies and Turkey ... places like that. We got together about $6,000 or $7,000 and stayed on a week or two more, thanks to him. And I gave him a role in the film. He wasn't an actor and he's very poor in it, but he was a big help in getting us the money."

Welles does not say which actor it was, so it will have to remain in the realm of speculation. When the money ran out again, actors began leaving production to take other jobs until more funding could be secured. Notably, Liammóir, his Iago, and Hilton Edwards, his Brabantio, returned to their native Ireland together (the two were boyfriends) to act in various theater productions. Once more funding was secured, Welles had to wait and wait and wait until everyone was free again.

Ultimately, shooting took about three years to complete. Welles said:

"So, even when I got the money, I had to wait until my actors were free, which made a long wait even longer than it took me to get the money. And when they were free, we went back again to Africa and then to Italy, where we shot all over the place and finished it. But that began the story of how long it takes me to make a movie. You know: 'Look at him — even on his own pictures, it takes him over three years to finish it.'"

Keeping in good spirits

One might be tempted to think that, because of the play's tragic subject matter, it was a dark and miserable shoot. On the contrary, Welles was quick to point out that the constant roadblocks were viewed with more bemusement than frustration. It seems he and his crew were happily able to roll their eyes at the all-too-predictable chaos that comes with filmmaking. Despite everyone's good humor, Welles quickly got stuck with the bad reputation he mentioned above. He also started to encounter production troubles on future films which were legitimately miserable. He said:

"Yes, it's still very prevalent, and it all began with 'Othello.' But the movie wasn't arduous — we had tremendous fun doing it and everybody got along awfully well. Our headaches were all riotous and amusing; it wasn't anguish like 'Mr. Arkadin' (1955) was. 'Arkadin' was just anguish from beginning to end. No, it was a very happy experience for me in spite of these terrible troubles."

Modern audiences, of course, may not be able to watch the 1951 version of "Othello" without confronting, first and foremost, Welles' own whiteness. The man was perhaps a brilliant actor and a fascinating Old World bon vivant, but he is also the product of a time when a white actor playing a Black man was considered acceptable. These days, Welles' "Othello" might be viewed as a curio for Shakespeare completionists.

At the heart of it, there is at least a wrenching, poetic script by one of the English language's most celebrated playwrights. One might still appreciate the Bard's words.