Glass Onion And Top Gun: Maverick Call Academy's Best Adapted Screenplay Rules Into Question

Mark Twain once wrote that "there is no such thing as a new idea," but apparently the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences disagrees with him because they have two categories for writing: Best Original Screenplay and Best Adapted Screenplay.

The distinction between the two should be pretty straightforward if you think about it. The nominees for Best Adapted Screenplay should be adaptations of pre-existing stories, and the nominees for Best Original Screenplay should not. Except sometimes that's not how it works.

At the 95th Academy Awards, two nominees for Best Adapted Screenplay blur the line between original screenplays and adaptations, and pretty roughly. These films tell brand-new stories, but they just happen to use at least one pre-existing character. That means they default to the "Adapted Screenplay" category, but is that really in the spirit of the award? Is that really the same job as "adapting" something?

And if it is, shouldn't all screenplays based on pre-existing characters fall under the same guidelines? Because they don't right now. Not by a long shot.

So let's talk about how the nominations for "Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery" and "Top Gun: Maverick" demonstrate how broken this system is.

Adaptation: Improbable

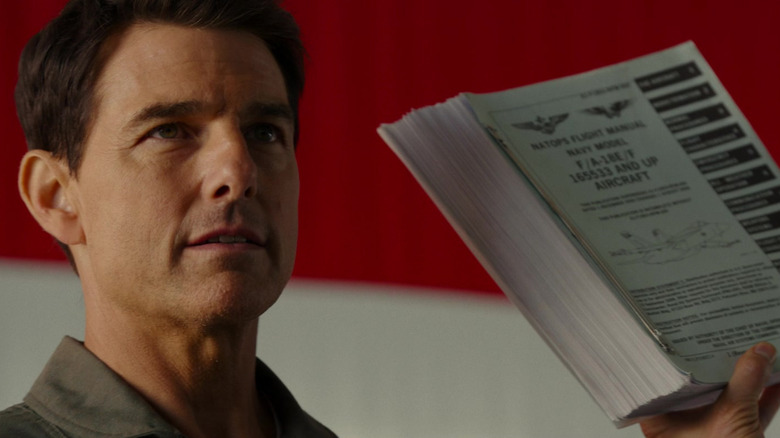

Rian Johnson's "Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery" and Joseph Kosinski's "Top Gun: Maverick" tell brand new stories about characters we have met before. In "Glass Onion," Detective Benoit Blanc from the 2019 film "Knives Out" embarks on an all-new mystery with all-new suspects, and in "Maverick," Captain Pete "Maverick" Mitchell from the 1986 film "Top Gun" is called back to his old military academy to teach an all-new class how to pull off a new, seemingly impossible mission.

Both films are clearly connected to the original but both films venture into new directions, with original storylines and characters. They are not retelling pre-existing tales, and yet both films are nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay because they are sequels.

The idea that all sequels are, by definition, "Adapted Screenplays" even if they aren't adapted from a specific story is nothing new. Movies like "Before Sunset," "Before Midnight," "Toy Story 3," and "Borat: Subsequent Moviefilm" have all been nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay under these same guidelines. The films were all brand new stories that just happened to feature pre-existing characters, and that's arguably distinctive from telling a brand new story altogether. Certainly, you've got the name and backstory of the protagonist already handed to you, but is it really the same thing as taking an entire pre-existing narrative and adapting that to the screen?

To put it another way, is inventing what happens next really the same as retelling what came before?

When is an original not 'original' at all?

It would be one thing if the Academy was extremely rigid about this, and they considered any movie based on pre-existing characters to be technically "adapted." But that's not even the case, because lots of films have been nominated for and even won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for telling pre-existing stories based on pre-existing characters. But they apparently get a pass because the stories and characters were real.

"Green Book," "Spotlight," "The King's Speech," "Milk." Are they great screenplays? Maybe (okay, maybe not "Green Book"). But original? That's a pretty big stretch. All of those Oscar winners — and nominees like "King Richard," "The Trial of the Chicago 7," "Judas and the Black Messiah," "Vice," "The Big Sick," the list goes on and on — are technically adapting a story for the screen. They just don't happen to be based on one specific text.

But if a film that adapts a real-life story can be "original" just because the producers didn't pay for the rights to one specific work, then surely it stands to reason that movies that tell brand new stories with pre-existing characters aren't necessarily "adapted," either. There's a grey area in here somewhere, the trick is simply acknowledging its existence and being fair about it.

What's in a rule?

The Oscars have a list of rules that they publish on their website, and the specifications for what qualifies as an "original" and an "adapted" screenplay aren't on it. But these debates have raged before and conclusions have already been reached. These are the laws of the land, but they shouldn't be. They don't allow for any nuance whatsoever, even though they are expected to reflect a medium full of nuance.

"Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery" and "Top Gun: Maverick" are not the most original movies ever made. They owe an enormous debt not just to their immediate predecessors but to their other inspirations. "Glass Onion" is a whodunnit in a gigantic tradition of whodunnits, which owes a heck of a lot to the film "The Last of Sheila" and the collected works of Agatha Christie. "Top Gun: Maverick" lifts most of its storyline from the final act of "A New Hope," and come to think of it, the final act of "A New Hope" almost completely ripped off the World War II drama "The Dam Busters."

But again, as Twain pointed out, there's no such thing as true originality. "Get Out" won Best Original Screenplay and it's abundantly clear that Jordan Peele watched "The Stepford Wives." "Django Unchained" won the same award, and it's the latest in a very long line of films about Western heroes named "Django." Heck, the original Django had a cameo in Tarantino's movie just to make the connection clear.

The Academy doesn't demand total originality from Best Original Screenplay nominees, and yet they have weirdly rigid rules about what qualifies as Best Adapted Screenplay. Are "Glass Onion" and "Maverick" truly original? Maybe not. But you could ask the same question this year about a movie that's nominated for Best Original Screenplay where they told Steven Spielberg's real-life story and changed the names.