Why The Fire Hunter Is Your New Anime Obsession

Spend enough time in anime fandom and you hear a common refrain: "They don't make shows like they used to anymore." Do they? There's plenty of great anime still being made: Fall 2022 alone brought an incredible bumper crop of anime series across multiple genres. Some may prefer the masterpieces of the past, but those masterpieces were exceptional even then. Even so, it is indisputable that certain kinds of anime are simply not made anymore. Original anime series are scarce. Modern shows rarely last beyond 12 or 13 episodes. Robots drawn in traditional 2D animation, outside of specialist studios like Trigger or Sunrise, are rare. Even the newest "Gundam" series, usually the industry standard for 2D giant robot shows, struggled weekly to maintain the standard of its mechanical animation. To find series like the long-running psychological thriller "Monster," or the slice-of-life mystery "Haibane Renmei," you have to go back 20 or 30 years in the medium's history.

At other times, though, the medium's history comes forwards 20 or 30 years to meet you. Such is the case with "The Fire Hunter," a fantasy saga set in a world where fire has been outlawed and hunters harvest the blood of fiends to power their machines. The first episode, which aired on January 14, 2023, is defiantly slow-paced. By its end, we have just barely met one of the main characters and have only caught a glimpse of another. Much of the time is spent watching people make paper, sell goods, and operate complicated machines in great detail. Modern audiences may be bored. But as far as I'm concerned, "The Fire Hunter" is 2023's fantasy series to beat.

Hound and sickle

"The Fire Hunter" befuddles from its opening minutes. It starts in medias res with a scene of shocking violence. Past the opening credits, we follow a young woman named Touko as she is made to take responsibility for what has happened. While Touko expresses her anxiety through her body language and facial expressions, we never once hear what she is thinking. It's a choice that diverges from many anime series made today that rely on inner monologue, often adapted from manga and light novels. "The Fire Hunter" feeds the audience information through its dialogue, but the show often cuts to seemingly unrelated scenes, setting details, and hand motions. Following the story necessitates paying close attention to both tracks so as not to be lost.

A narrator is introduced 11 minutes in after making a brief appearance in the opening scene. But the narrator overwhelms the audience as often as she clarifies key details. "That night a man they call a 'fire hunter' died," she says in the beginning, "leaving behind only his hound and sickle." But why does a fire hunter, whatever that might be, need a hound or a sickle? Later, the narrator explains that "Once, humans could make fire and use it as they pleased. But then, the human race was remade." What? Some critics have taken "The Fire Hunter" to task for relying on a narrator at all, rather than allowing the characters and setting to speak for themselves. I partially agree, but at the same time a narrator is a tool like any other. The narrator of "The Fire Hunter" conveys a certain old-fashioned atmosphere, while maintaining tight control over what the audience knows and what they do not.

Fiend blood

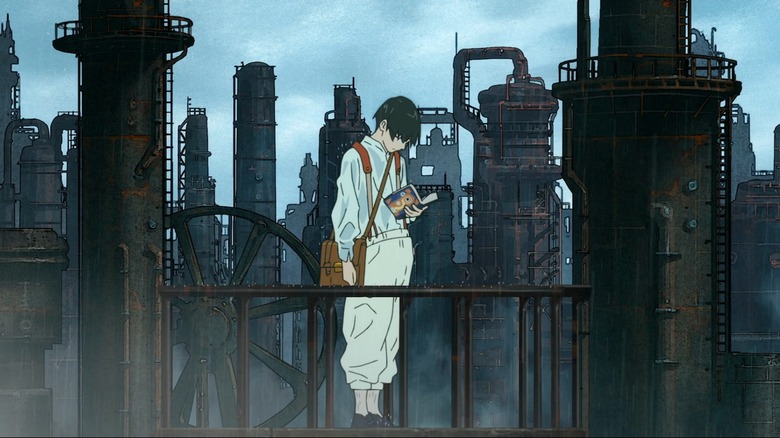

The aesthetics of "The Fire Hunter" are similarly rooted in the past. Touko's older family and neighbors are rendered fairly realistically. The first episode devotes far more time to their day to day lives than the slaying of the fiend that opens the series. In contrast to its naturalistic depiction of human society, the supernatural is captured in extremes — the sickly yellow of fiend blood, the thick brush strokes of the slaying, and the fire that warps human bodies. When a fiend appears on screen, everything in the world moves constantly and unnaturally. By comparison, key moments in the lives of Touko and the show's second protagonist, Koushi, are rendered as illustrated "postcard memories" popularized by Osamu Dezaki. The turn from cool "stillness" to red-hot chaos is rarely seamless, but speaks to the story's greater worldview.

If "The Fire Hunter" is reminiscent of the work of older artists, that is because its creative team is made of older artists. The most famous of them is scriptwriter Mamoru Oshii, the famous director of "Ghost in the Shell" as well as much of the '80s classic "Urusei Yatsura." He is joined by a number of his friends and allies, including director Junji Nishimura and composer Kenji Kawai. Legendary voice actor and vocalist Maaya Sakamoto (of "Escaflowne" fame) sings the ending theme, while a shot in the opening credits of a woman standing on a tree branch is lifted directly from fantasy classic "Record of Lodoss War." It should also be noted that the illustrator for the original "Fire Hunter" novels, Akihiro Yamada, also drew the covers for the beloved fantasy novel series "The Twelve Kingdoms."

Fire on the wind

Rather than Mamoru Oshii, I think Junji Nishimura represents a better gauge as to what to expect from "The Fire Hunter." Nishimura's output is wide-ranging and includes solid work, outright trash, and a handful of hidden masterpieces. His 2004 series "Windy Tales" is a visually astonishing slice-of-life series made at the prestigious Production I.G. But his 1996 fantasy adaptation "Violinist of Hameln" features so little movement that fans dubbed it "Slideshow of Hameln." Personally speaking, I suspect these two series are key to what "The Fire Hunter" is doing. The show's use of still images, pans, and pointed cutting around character face and bodily movement are reminiscent of the budget-saving tricks of "Hameln." At the same time, though, these decisions are evocative in their own right, building the world and atmosphere of "The Fire Hunter" through implication. Meanwhile, the animation during fiend sequences bear comparison to the stylization of "Windy Tales," even as they fail to match its technical expertise.

While I'm loving the series so far, I have to admit that Nishimura and Oshii are playing a dangerous game with "The Fire Hunter." Its detailed character designs, careful storyboarding, and elaborate world all require time and effort to maintain. These qualities are in short supply within today's overstretched anime industry. The show's studio, Signal.MD, was recently behind the disastrous adaptation of "Platinum End" (based on a series by the creators of "Death Note"). Even before that, though, the studio made the news when Japan's FTC caught them refusing to pay a subcontracted animator who worked for them in 2019. An environment like this could spell doom for "The Fire Hunter," even if its key creative staff are veterans.

Out of the past

I'll admit that my admiration for "The Fire Hunter" is rather selfish on my part. For the past several years, fantasy anime has been dominated by stories that borrow from Japanese role-playing games and MMORPGs. Many are sourced directly from webnovels, whose passionate authors often prioritize indulgence over originality. The protagonists hail from modern Japan, or are simply reborn in the bodies of local people. These stories aren't without their charms: "Mushoku Tensei" at least has great animation, while "So I'm a Spider, So What?" has a wild conceptual hook. (The protagonist is a spider!) Personally, though, I can't help but find these kinds of reincarnation stories to be cowardly. Rather than build a setting that speaks for itself, the majority of Japanese fantasy novels adapted into anime are masturbatory power fantasies coated in a thick layer of irony.

There have always been novels like "The Fire Hunter" being written in Japan. Manga translator Jocelyne Allen has been championing Chisato Abe's "Yatagarasu" stories for the past few years. More recently, Mizuki Tsujimura's "Lonely Castle in the Mirror" was adapted into a film in 2022. It's rare, though, that we see these stories make their way to TV outside of manga adaptations. "The Fire Hunter" may have only been possible due to Mamoru Oshii and Junji Nishimura's industry clout. The confidence with which it builds a world, and populates it with ordinary people living their lives in a fantastic setting, should not be a rarity in this industry. Yet "The Fire Hunter" remains just out of step, a relic of an earlier time when production companies would occasionally finance weird, slow-paced passion projects. I wish it came about in better circumstances, but I'm also grateful this old-fashioned tale exists at all.