Avatar Is Impressive, But Skinamarink Is On The Real Frontier Of Filmmaking

Did you know that "Avatar: The Way of Water" used revolutionary underwater motion capure techniques? Did you know director James Cameron used high frame rate (HFR) for certain scenes? Did you know it took 13 years to make? You probably did know most of that because technical innovation and pushing digital graphics to their limits are basically the movie's main selling points. Cameron's follow-up to 2009's "Avatar" has been heralded as a pioneering step in digital effects — a 3 hour and 12 minute technical marvel that has already made $2 billion at the box office.

Cameron did infuse the film with some real-world relevance by exploring weighty themes like colonization and humanity's destruction of the natural world. But while this allegorical element can be effective, ultimately "The Way of Water" works best as spectacle. It's all very impressive, but for me, the "Avatar" movies just never seemed all that exciting. As our review puts it, "There's only so much artificial beauty we can handle before we start to get weary and, well, bored." And in an age of CGI fatigue, these films feel like more of the same rather some profound cinematic leap.

Which is why, in 2023, it's so refreshing to have other movies that actually do feel like they're expanding the frontier of filmmaking, e.g. "Skinamarink." Director Kyle Edward Ball's micro-budget horror effort might not have hi-fidelity 3D models of giant blue creatures or expertly rendered sub-surface scattering, but in my view it represents something much more exciting and, yes, boundary-pushing.

Skinamarink's mini buzz

"Skinamarink" defies easy categorization. Depending on who you ask it's either a grainy hour and 40 minute experimental exercise in "vibes," a devastating exploration of childhood abuse, or a strong narrative-led horror that might just be the scariest movie ever made. But whatever you think of the film, there's no denying that it's causing a stir of its own. It might not be a "The Way of Water"-level stir but the film has been snapped up by IFC Midnight for theatrical release and brought in $1 million in its first week at the box office. That might not seem like all that much, especially relative to Cameron's blockbuster and its historic box office performance. But considering "Skinamarink" cost just $15,000 to make and was shot entirely in Ball's childhood home, it's a significant milestone.

The buzz surrounding the film began when it was pirated in 2022 and unleashed on the Internet for the hungry TikTok and YouTube crowds to devour and proclaim as the "most disturbing horror movie" and the film "traumatizing everyone on TikTok." In that sense, "Skinamarink" gained an almost mythical reputation before it had even been officially released. What was this cursed footage seemingly traumatizing the internet?

Now, with its theatrical run and an upcoming streaming release on Shudder, "Skinamarink" is in the process of transcending internet infamy to cause some wider cultural waves. It's obviously not going to get anywhere near "Avatar" levels of cultural impact, but it's certainly exceeded any reasonable expectations. And I think that's the first sign of something bigger to come.

The power of the internet in film

Ball's film was always going to prove popular online because, in a way, it is of the internet. The Canadian filmmaker was inspired by numerous online resources, from subreddits like r/liminalspace to his own YouTube channel, Bitesized Nightmares, where he would turn viewers' recollections of their nightmares into short films. In this way, he was, as he put it in a recent interview, "doing research on what scared people, or at least what their subconscious thought scared them."

Having become intimately familiar with the language of the subconscious and how it manifests in nightmares, Ball was operating from a truly unique position when it came time to craft the horror of "Skinamarink" — all of which wouldn't have been possible without the internet. Perhaps that's why he went so far as to claim: "The internet has been my co-director."

With all that in mind, I would argue "Skinamarink" has an almost revolutionary potential. The film feels like the cutting edge conversations and once-esoteric sensibilities developing online have finally coalesced into something that could genuinely influence the course of moviemaking. I know that sounds grandiose, and I don't think that "Skinamarink" alone will change the future of cinema (though it's possible). But I do think it's one of our first glimpses at a new cinematic era defined by directors raised on the trends of the internet and shaped by its significant power to democratize previously prohibitive tools. And, like the New Hollywood movement of the '60s and 70s, this new guard — let's call them Post Hollywood — will use film to not only tell stories in new ways, but to convey feeling and experience in a way that has, as yet, not found expression in popular film. That is exactly what Ball has done with "Skinamarink."

Avatar's technical achievements

Before we delve deeper into Ball's movie, let's not do "Avatar: The Way of Water" a disservice. There's no denying the level of craftsmanship and pure graft that has gone into making this film. From underwater jetpacks to AI-assisted animation, the sci-fi sequel uses a stupefying array of technical innovations. Plot-wise, we see Sam Worthington's Jake Sully, and Zoe Saldaña's Neytiri escape with their children to an entirely new area of the fictional world of Pandora, which required Cameron's team to develop new tools to render the aquatic-based story — including "computational fluid dynamics simulations," which ... cool? Anyway, the point is that Cameron and co. really were pushing technical boundaries with "The Way of Water."

Elsewhere, there's the use of HFR to, as Cameron put it, "improve 3D where we want a heightened sense of presence." The effect is actually pretty distracting, and no matter how many great directors get behind HFR, it will always make things look less cinematic and more like a daytime soap. That said, it's yet another example of how Cameron and his team were experimenting, which they did seemingly without pushing their VFX artists to breaking point — a refreshing approach in the age of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and its recent controversies.

And, unlike the MCU, Cameron's "Avatar" saga reasserts the importance of evaluating movies on their own merits, rather how well they relate to some wider cinematic universe, leverage fan nostalgia, or adhere to audience demands. That's a great thing! But without taking away from the technical achievements of the "Avatar" movies, in terms of truly boundary-pushing ideas, it really feels as though "Skinamarink" has more to offer.

The margins of reality

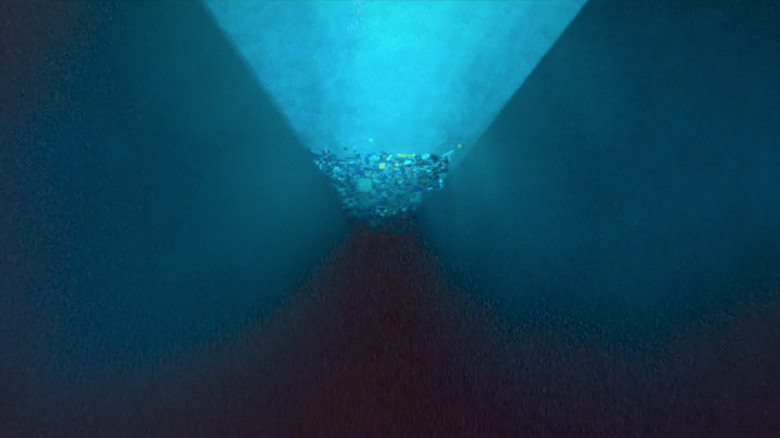

While "The Way of Water" has drawn in crowds with the promise of cutting-edge computer graphics and a truly immersive virtual world, "Skinamarink" has provided its audience with just as immersive an experience while using little to no digital effects in the process. Ball's film relies on a rich medley of cinematic techniques, aesthetic choices, and novel ideas to transport viewers into a oneiric nether world that feels all-enveloping in a way I've personally never experienced before.

These techniques and inspirations are too numerous to list in their entirety. But central to the film's tone and visual style is the idea of liminality. A crucial element of Ball's short films and his full length feature, liminality as a concept obviously predates the internet but has found new forms of expression online. The aforementioned r/liminalspace is a great example of how liminality as an idea has fostered a whole aesthetic movement which mixes nostalgia and familiar imagery with a dark undertone, depicting spaces that are, according to the subreddit, "Abandoned, and oftentimes empty — a mall at 4am or a school hallway during summer."

One significant example of liminality in online media is Backroom Videos, which developed from an image of what looked like a windowless office hallway posted to online message board 4Chan. The picture was promptly used as the basis of multiple creative projects, including perhaps the most famous example from VFX artist Kane Parsons (aka Kane Pixels). "The Backrooms (Found Footage)" caused enough of a stir that even the boys over at Corridor Digital had a go at breaking down its use of VFX, VHS filters, and the all-important element of liminality. The style has since become much more widespread, with numerous Instagram profiles such as "In The Margins of Reality," cropping up, dedicated to the burgeoning aesthetic.

Subverting nostalgia

That's all well and good, but what does it have to do with "Skinamarink"? Or "The Way of Water," for that matter? Well, in the former's case, throughout Ball's 100 minute terror fest, that feeling of something being slightly off yet familiar is ever present. Ball spoke about his familiarity with r/liminalspace and the closely-related r/weirdcore to RogerEbert.com. The sensibilities of both pervade "Skinamarink," which is set in 1995 and features multiple shots of '90s suburban minutiae. The two children in the film, Kevin and Kaylee, are surrounded by these shreds of nostalgia — CRT TVs, wood paneled walls, lego bricks scattered on beige carpets, and the real star of the movie: that god-forsaken chatter phone.

But unlike the cynical nostalgia plays of other modern media, Ball's film subverts these nostalgic images by turning things quite literally on their head. The cartoons Kevin and Kaylee watch for comfort become distorted as the film progresses, symbolizing the upending of familiarity and the creeping entropic energy that ultimately subsumes the children's home. The chatter phone gets a suitably horrific makeover by way of a jump cut that is arguably the movie's biggest scare — that creeptastic ending notwithstanding. Hallways are turned upside down, toys stick to ceilings. Everything familiar and comforting is subverted.

This is all the language of these aesthetic movements that originated online. At one point, cryptic text appears suggesting Kevin has been trapped in this liminal nightmare for 572 days. That shot itself could have been lifted straight from the r/weirdcore subreddit. By utilizing these styles, "Skinamarink" is, whether intentionally or not, a direct refutation of the recent boom in nostalgia bait and feels like it's in conversation with our current cultural moment, tugging at the fraying edges of our artistic frontiers.

Destabilizing reality

In 2021, director Jane Schoenbrun debuted their film "We're All Going To The World's Fair." It tells the story of teenager Casey, who mostly spends her life online: exploring the far reaches of the internet from her suburban bedroom. Once she gets involved with an online horror role-playing game, things take an unsettling turn as she becomes more removed from physical reality in search of transcending her daily life and reconciling her issues with identity.

Schoenbrun has been a vocal supporter of "Skinamarink," telling Variety:

"It's maybe the only movie experience I've ever had that fully captured a unique feeling of terror that I think a lot of people in my age bracket felt as kids online, reading scary stories or watching apparently 'cursed' videos on the internet in the middle of the night."

They went on to highlight the "liminality of reality" that occurs at night and praises how "Skinamarink," "commits so fiercely to that feeling and trying to create an experience for viewers that destabilizes and breaks reality." That ability to "destabilize" reality gives Ball's film the feeling of a whole body experience that big-budget blockbusters like "Avatar: The Way of Water" can't hope to emulate; box office expectations and studio oversight keep them beholden to traditional modes of storytelling and filmmaking even as they push the boundaries of the technology used in the process.

"Skinamarink" on the other hand, is decidedly not beholden to any preconceived notions of filmmaking, storytelling, or artistic expression — which not only makes it a powerful, immersive experience, but also gives it real-world destabilizing power.

Disrupting filmmaking

"Skinamarink" feels more significant than the similarly lo-fi "We're All Going To The World's Fair," mainly because Schroenbrun's film, though informed by its director's experiences growing up with the internet, is a movie about the internet. "Skinamarink," on the other hand, feels like a product of whatever collective consciousness has formed online. It's not about how the internet has affected the world; it's an example of it.

What's more, unlike much of the analogue horror videos to which it's so closely related, there's no conceit on which "Skinamarink" relies. This isn't strictly a found-footage film, nor is it supposed to be some sort of recently unearthed cursed TV broadcast. It's just what it is — a liminal hypnagogic spasm of pure, unadulterated fear, painted with textures of '90s nostalgia, emerging aesthetic movements, and experimental film.

"Skinamarink" obviously isn't the first piece of media to experiment with these kind of aesthetic and tonal choices, but it feels like the first to transcend more niche platforms and see notable success. And this is where it's real-world destabilizing power comes in. The analogue horror movement, which makes similar use of darkly nostalgic imagery and themes, has thus far mostly been confined to serialized YouTube videos. Even something like Alan Reznick's "This House Has People In It," which gained significant attention for its deeply disturbing depiction of a family home descending into surreal, paranormal chaos, was distributed by Adult Swim. That's a win for Reznick and for viewers, but it's not an international theatrical distribution deal or $1 million made in a week. Which is why "Skinamarink" feels like the start of something bigger.

Skinamarink's relevance

Not only is "Skinamarink" on the frontier of artistic expression, it feels more relevant than any blockbuster sci-fi outing, regardless of how many real-world allegories those blockbusters throw in. When the '90s ended and the internet became a ubiquitous presence in all our lives, we witnessed the slow death of the monoculture — a time when most people consumed the same media and had a similar shared experience of culture. It's been argued that the monoculture is a myth, but there's no doubt media and access to it was much more restricted prior to the proliferation of the internet. These days we have instant access to not just information, but to any number of niche interests. The internet has, for better or worse, allowed anyone to immerse themselves in any subculture, any interest, any moment in history at any time.

With "Skinamarink," Ball captures that very feeling, combining the look of a '70s film with cartoons from the '50s, a heavy dose of '90s nostalgia, and all within the framework of distinctly modern and progressive ideas that have provided fertile ground for multiple theories about just what is happening in "Skinamarink." What could be more representative of our current state than this wild combination of influences and styles? I'm not saying Ball intentionally did this, but his film, by virtue of the varied tastes and Ball's ability to access various parts of cultural history (again, thanks to the internet), taken on this almost multiversal aspect.

In that way the film is so much more relevant to our current place in time than allegories about environmental conservation. Everything and every time in recent history is present at once in "Skinamarink," just as it is in our modern lives. There couldn't be a more relevant movie in 2023 than this.

Horror vs sci-fi blockbusters

Much of the success of "Skinamarink" is likely down to the fact it couldn't have arrived at a more auspicious time for horror movies, which are still the only thing besides superhero blockbusters that reliably bring people out to the multiplex. As Ball told Fangoria: "It feels like ever since 'The Babadook' we've been in a horror renaissance that feels like it keeps going. I really think horror is the most interesting genre, and you can only count a few times in cinema history when horror wasn't going crazy and reinventing."

In contrast, "Avatar: The Way of Water" and its technological advances simply doesn't seem to have as much potential to reinvent. Sure, Wētā FX, the company behind all the pioneering digital effects, developed a host of innovative new patents in the 13 years it took to craft the movie, which will no doubt make future VFX artists' jobs much easier. And the film's outrageous success at the box office will hopefully go some way to convincing studios that original ideas can still triumph over franchises and existing IP. Perhaps its environmentally-focused story will indeed cause future generations to think more deeply about the plight of our planet, which would be an incredible achievement.

But art has always been used as a vessel to deliver sociopolitical messages and to encourage action, often with significant results. That's not necessarily pushing the boundaries of filmmaking. And "The Way of Water," rather than feeling like its main purpose is to incite activism and promote change, can often feel like one long tech demo, proudly lingering on stunning shots of Pandora and existing as a showcase for CGI developments, even while its story hits some admittedly poignant beats.

Skinamarink vs Avatar

In an interview with Filmmaker magazine, Schoenbrun spoke about the "'cursed image' thing," "grain haziness," and "things bleeding through low resolution that feel not quite right," surmizing that, "Kids were pushing in experimental new directions for a minute there in a way that could only be utilized on the internet."

But that's the remarkable thing about "Skinamarink." It's taken that aesthetic of "grain haziness," and "things bleeding through low resolution" and proven they not only work outside the internet, but bring much needed innovation to a filmmaking industry that feels like it's severely lacking in that regard. As millennials reach the age where they reckon with their upbringings and their nostalgia for the late '90s/early-2000s, the internet has functioned as a kind of collective consciousness wherein those feelings find expression — often with somber overtones that reflect a sense of lost innocence and disappointment with the reality of adulthood in the 21st century. For these ideas to have transitioned from subreddits and Twitter threads to a widely distributed feature film feels like a seminal moment in the evolution of cinema and popular culture in general.

I don't mean to be glib, but in the face of all these fascinating ideas finding expression through a new generation of filmmakers and their experimental projects, the fact that Cameron's team developed new cameras for "The Way of Water," just seems comparatively mundane. Ultimately, does the "Avatar" saga have the same potential to inject radical ideas and concepts into the public consciousness as "Skinamarink" — to "go crazy and reinvent" in the way Ball and his contemporaries have? To potentially help usher in a new wave of cinematic artistic expression? With all due respect to James Cameron and his unimpeachable standing as one of the greatest to ever do it — I honestly don't think so.