David Crosby's Father Was An Acclaimed Cinematographer With A Filmography That'll Boggle Your Mind

The recent passing of David Crosby was an enormous blow to the world of music. As a member of the Byrds, and one of Cosby, Stills & Nash, David Crosby helped revolutionize the folk-friendly arm of the entire 1960s rock scene. Compared to the kid-friendly bubblegum pop of the era, Crosby's work was more touching, emotional, and intelligent. He will be missed.

Also, Crosby grew up with an Oscar in his house. As it happens, David Crosby's father was none other than the Academy Award-winning cinematographer Floyd Crosby.

Floyd Crosby is not necessarily a household name, but his career as a cinematographer spanned over 30 years. Indeed, Floyd's career got an enormous kickstart in 1931 when he filmed F.W. Murnau's silent semi-documentary "Tabu: A Story of the South Seas." That film aimed to tell the authentic story of life on the island of Bora Bora, and, for the most part, cast only local talent to prey its main roles. "Tabu" is perhaps well-meaning for a film made in 1931, and, in terms of cultural sensitivity, availed itself far better than the same year's "Trader Horne." It still bears a lot of screenwriting clichés and no small amount of ethnographic othering, however.

The black-and-white cinematography, however, was first-rate and featured many lovely outdoor and ocean scenes. The film makes Bora Bora look like a blissful and beautiful place to live. One can sense James Cameron likely internalized elements of "Tabu" to make "Avatar: The Way of Water." It was Crosby's first major job, and he received an Oscar for his efforts.

The lost film, the crab film

In the 1940s, Floyd Crosby worked as a cinematographer for the United States military, shooting training videos and combat footage to aid in the American war effort. He made some brazen propaganda films with titles like "Look to Lockheed for Leadership" as well as cautionary films like "Traffic with the Devil." The latter, a classroom scare film about driving safety in Los Angeles, was part of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's "Theatre of Life" series and was nominated for an Academy Award. In the 1940s, Crosby also worked briefly for Orson Welles on the unfinished, $1.2 million picture "It's All True," which was meant to follow up "The Magnificent Ambersons." According to the 1993 documentary film "It's All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles," the movie was shot on highly flammable nitrate film stock (common for the era) which, in the 1960s, had to be disposed of, lest it start fires in film vaults. As a such, lot of "It's All True" ended up on the floor of the Pacific Ocean. It, too, was a semi-documentary.

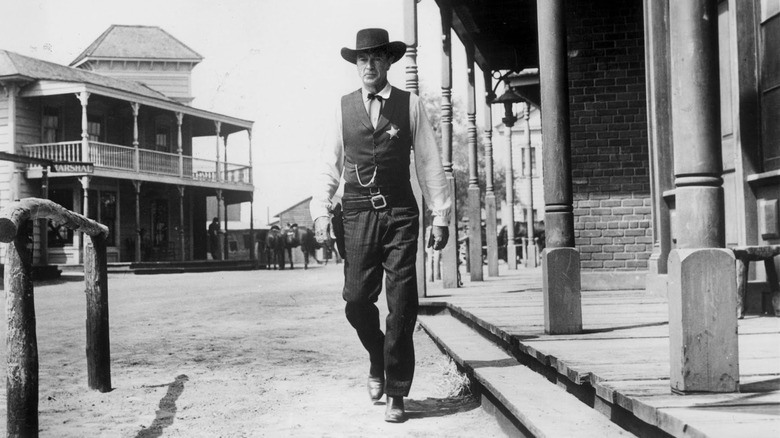

Crosby's knack for natural, documentary-style photography served him well in shooting scripted features as well, and, in 1952, received a Golden Globe for his work on Fred Zinneman's Western "High Noon" starring Gary Cooper. "High Noon" was nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, but lost that year to "The Greatest Show on Earth."

It would also be in the 1950s that Crosby would begin a long and lucrative career working for legendary B-movie director and producer Roger Corman. Corman's first film as director was 1954's "Five Guns West," which Crosby shot. Over the next few years, the two would collaborate on flicks like "Naked Paradise," "Attack of the Crab Monsters," "Rock All Night," and "She-Gods of Shark Reef."

A-Films and B-Films

For the next 20 years, Floyd Crosby would rotate between shooting high-profile studio films, and enjoyable low-rent schlock. One year, Crosby would be filming an adaptation of "The Old Man and the Sea" for director John Sturges, before turning around to shoot "The Screaming Skull," a bizarre haunted house film that found its way into the arms of "Mystery Science Theater 3000."

In the 1960s, Crosby, with Corman, helped create a certain subset of horror movies, having shot several of the director's celebrated adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories. Corman's Poe movies all feature, bright, clean, colorful, gloriously artificial photography, making the blood stand out and making all the actors look very deliberately like wax caricatures. The films were just as funny as they were scary, and prove that one can create frightful images out of blazing lights and colorful sets. Crosby shot "House of Usher," "The Pit and the Pendulum," "The Premature Burial," "The Haunted Palace," the anthology film "Tales of Terror" (one of this author's favorites), and the 1963 version of "The Raven." Many of these starred Vincent Price and Peter Lorre in some capacity.

Crosby also shot one of the more striking and bizarre horror films of the 1960s, "X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes." In that film, Ray Milland plays a scientist who develops a miracle eye drop that gives him x-ray vision. However, he begins seeing through all matter and starts to perceive the world as abstract shapes. By the end of that film, he will go mad from this power, and it's implied that he is seeing sin. It's a gorgeous and weird movie.

Crosby's final film was "The Cool Ones" in 1967. He retired after that. He passed in 1985.