The 14 Greatest Opening Scenes In Sci-Fi Movies

Sci-fi movies live or die on their opening scenes. In a genre driven by awe, wonder, and an unrecognizable — yet familiar — sense of place, it's crucial to evoke these emotions as quickly and potently as possible. Get it wrong, and you risk underwhelming your audience from the get-go. Get it right, and they'll be like putty in your hands.

What makes a great beginning, then? Well, pretty much anything goes in the world of science fiction: An opening scene can be terrifying, beautiful, action-packed, or anywhere in between. The best sci-fi films of all, though, grip the viewer from the very first shot, take them away to another time, world, or civilization, and keep them enthralled until the credits roll.

With all this in mind, it should come as little surprise that the most effective opening scenes in sci-fi history tend to be attached to the most widely-beloved movies in sci-fi history. From the dawn of man to the depths of outer space, these are the greatest of them all.

2001: A Space Odyssey

The "Dawn of Man" sequence in "2001: A Space Odyssey" begins, fittingly, in darkness. After the unnerving chaos of the movie's three-minute overture subsides, the film kicks off with a shot that has since become one of the most recognizable in cinema: sunrise over Earth, set to Richard Strauss' "Also sprach Zarathustra." Over half a century later, it's easy to write off this moment as pop culture wallpaper — oh yeah, it's that bit from "2001" — but it really doesn't deserve such indifference. In just a few seconds of screen time, Stanley Kubrick's sunrise introduces that dreadful feeling of cosmic wonder for which the film is so renowned.

"2001" doesn't let up from there, either. As Kubrick tells his self-contained tale of the evolution of mankind, he uses no dialogue whatsoever, instead relying on the strength of his cinematography, sound design, and score. For the coup de grace, the sequence employs a match cut that has since become iconic, as the apes' first tool soars through the air to become a satellite in orbit over Earth.

It's also worth mentioning that this scene was as groundbreaking as it is powerful. According to a Vanity Fair feature on the making of "2001," Kubrick used a then-experimental concept known as front projection to augment his soundstage, having failed to secure a location shoot in Africa. That's "Dawn of Man" all over, though — not just captivating, but technically flawless, too.

Star Wars

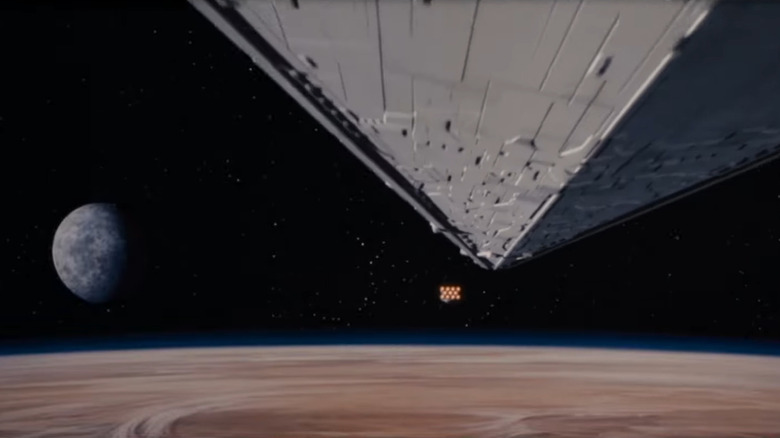

Nobody knew what they were in for when "Star Wars" premiered in 1977. Coming almost out of nowhere, the movie that would later become known as "A New Hope" made over $775 million at the box office, spawned a boundless franchise, and forever changed the sci-fi landscape.

A long time has passed since then, and many of us have seen "Star Wars" over and over again, but the impact of that first battle over Tatooine never diminishes. From the remarkable VFX to John Williams' timeless score, there's a lot to love about the opening shot in particular,, but nothing hits you quite like the size of the Star Destroyer. Seeing that thing for the first time, it's impossible to believe that it can get any bigger, and yet it still keeps coming, filling the screen until there's nothing else to see. The Rebels' last stand only becomes more thrilling afterwards, as a company of stormtroopers wipes out the Tantive IV's crew and Darth Vader makes his unforgettable entrance.

The franchise has attempted to illustrate the awesome might of the Empire to various degrees of success over the years, but no movie or TV show in the galaxy far, far away has done it as effectively as the first three minutes of "Star Wars."

The Matrix

Going into "The Matrix," you only need to know three things: Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) is a badass, the agents are terrifying, and the Wachowski sisters can direct an action scene like nobody else. Luckily, the movie's first scene proves each of these truths with aplomb.

The whole sequence pivots around one moment. After the police move in and seem to apprehend Trinity, Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving) and his two colleagues arrive on the scene. When the officer in charge insists that his team can handle "one little girl," Smith replies: "No, lieutenant, your men are already dead." It's a killer line, one that upends your expectations and hypes up the movie in equal measure, and the ensuing throw down is as close to perfect as you'll find in the late '90s. Trinity's fight with the cops and escape from the agents is a masterclass in action choreography: The 360-degree kick is probably the most famous shot of all, but the rest of the scene more than lives up to it, featuring superb wire-work and just enough quiet tension to keep you on edge (case in point: Trinity's terrifying stand-off with the broken window.)

On top of all that, the Wachowskis' bold use of lighting, eccentric camera angles, and the split diopter effect gives the whole scene a distinctive noir vibe that fits the movie's dark sci-fi style to a tee. Honestly, it's almost unfathomable that "The Matrix" was the two sisters' first outing as action directors. This opening scene is crafted with more skill and talent than many filmmakers exhibit in their entire careers.

Alien

"Alien" is a film founded on the idea that less is more. The xenomorph isn't born until about halfway through, and after that it's rarely seen in full. Jerry Goldsmith's avant-garde score is unobtrusive; at times, it's entirely non-existent. Even the sets and costumes employ the sort of utilitarian simplicity you'd expect in a story about space truckers. In less capable hands than Ridley Scott's, these creative decisions might have worked against the movie, but here they work in concert to establish a grounded vision of a wretched future — and set the stage for the xeno's rampage.

This ethos is obvious from the first scene in "Alien," which is essentially three minutes of nothing happening in space. The Nostromo's debut is all the more eerie for the total absence of any cast or dialogue, and the deep rumble of the ship's engines (along with Goldsmith's music) is more than enough to keep you on edge. This peek into the labyrinth pays dividends when the alien threat finally emerges and the crew are forced into a fight for survival. Introducing the ship as a character itself aligns nicely with the concept of MOTHER and its eventual betrayal of the crew.

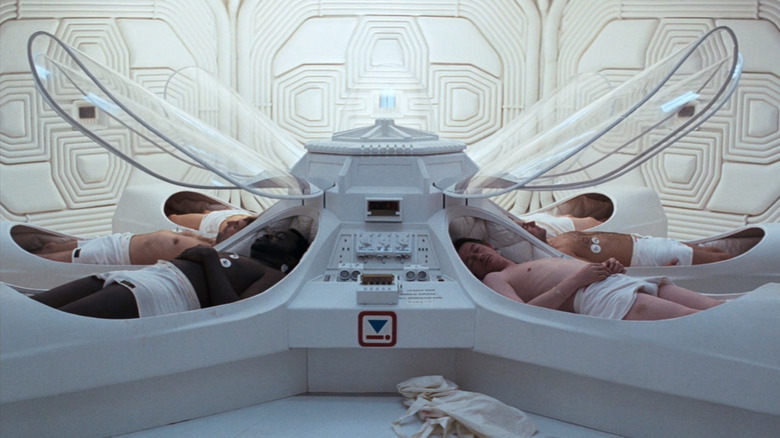

When the humans of "Alien" finally appear on screen, they're snoozing in coffin-like hypersleep chambers, utterly still and pretty much helpless until the lights come up. It's not exactly subtle as far as symbolism goes, but it still makes for a creepy ending to a surprisingly scary opening.

Jurassic Park

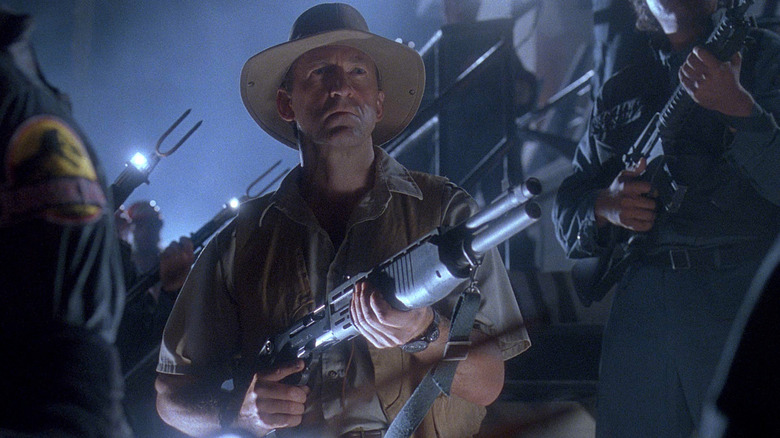

The first scene in "Jurassic Park" is founded very much on the idea that more is more. Much of the first half of the movie is preoccupied with corporate espionage and the magic of genetic science, so it's important that the opening demonstrates the dinosaurs' peril in no uncertain terms.

And boy, does it succeed. The concrete paddock and dozens of armed workers immediately indicates that these dinos aren't messing around, but the real triumph here is the velociraptor's ingenious escape scheme: At the crucial moment of her release, she charges backwards into the crate, sending the poor gatekeeper tumbling into her clutches. The park's carefully-planned operation devolves into a frenzy of screams and screeches as the other workers try — and fail — to free their colleague.

At its climax, as Muldoon (Robert Peck) cries out for his men to shoot the raptor, the gatekeeper's hand slips away, and John Williams does his thing, the scene becomes a thrilling bout of pandemonium, one that leaves enough of an impression to keep you going through the next hour of chaos theory.

Blade Runner

The first shot of "Blade Runner" is known as the "Hades" landscape. This vast depiction of the dystopian Los Angeles skyline was painstakingly crafted using acid-etched models, smoke, fiber-optic cables, and matte paintings. The result? A vision of the future that, in 1982, was unlike anything that had ever been put to screen. The horrors of the L.A. vista, and those that follow, are matched only by the beauty of the brief "eye" shots that are cut between them, a contrast that encapsulates the unsettling and astonishing world that Ridley Scott brings to life with his neo-noir masterpiece.

The Voight-Kampff test, and the subsequent confrontation between Leon (Brion James) and Holden (Morgan Paull), is just the icing on the cake. What begins as a surreal, almost nonsensical interrogation quickly grows into a tense showdown between man and machine, and the realization that Leon is a replicant seems to strike Holden at exactly the same moment that it hits the viewer. After that, it's obvious that the meeting can only end in violence — but it still comes as a shock when it happens.

There's more to this moment, too. It's easy to miss, but after he's killed, you can briefly see that Holden had a gun in his hand. The premise of "Blade Runner" rests on the moralities of mankind and the perceived differences between replicants and humans, and it speaks volumes that, even in this initial display of a replicant's murderous nature, his human counterpart was just as ready to pull the trigger.

Dune (2021)

If Denis Villeneuve knows anything, it's scale. His more recent films, such as "Arrival" and "Blade Runner 2049," are permeated by a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur that makes him one of the best science-fiction directors working today. Nowhere is this more apparent than in "Dune," Villeneuve's 2021 adaptation of Frank Herbert's legendary sci-fi novel.

"Dune" opens on a line that you won't find in the book, spoken in the deep, guttural form of the Sardaukar language and utilizing the kind of sound design that must be heard in a theater: "Dreams are messages from the deep." The subsequent introduction to the Fremen and Harkonnen during an ambush on the latter's spice harvesters is all the evidence you could ever need of Villeneuve's knack for conveying scale, as well as that of his cinematographer, Greig Fraser. Technically speaking, what makes this scene great — the production design, the deft use of CGI, Hans Zimmer's score — also happens to be what makes the rest of the movie so good. It's everything that works about "Dune" in miniature.

The sequence is capped off by another original line. Over a shot of the Harkonnen forces departing Arrakis, Chani (Zendaya) wonders, "Who will our next oppressors be?" Like the scene that preceded it, Chani's question is haunting, exciting, and provides a tantalizing glimpse of the brilliance to come.

The Terminator

Okay, I know what you're thinking. Why would anyone choose the intro to "The Terminator" over the opening battle in "Terminator 2: Judgement Day"? After all, "T2" has that famous shot of the T-800 stomping a human skull, better VFX, more action, and a smoldering, scarred John Connor (Michael Edwards) watching over it all. Is the original's first scene really better than that?

The answer, of course, is yes, and it all comes down to tone. Sure, the "T2" scene is fun, and it does a decent job of introducing the myth of John Connor. However, at the end of the day it's little more than an action scene. By contrast, the "Terminator" opening is exactly as bleak as the concept of the Future War demands. There's no epic battle here, no heroic stand against the machines — only the charred rubble of Los Angeles, a sea of skulls, and a single, desperate soldier fleeing from the lights of the HK-tanks. More extermination than war, this scene establishes the rest of the movie's hopeless tone.

The opening of "The Terminator" is then rounded off by what must surely be the greatest piece of expository text in the history of cinema: "The machines rose from the ashes of the nuclear fire. Their war to exterminate mankind had raged for decades, but the final battle would not be fought in the future. It would be fought here, in our present. Tonight ..." How's that for setting the scene?

Children of Men

"Children of Men" couldn't possibly have a darker premise. In 2027, mankind has become infertile, leading to the near-total obliteration of human society. When the film opens, the youngest person on Earth, 18-year-old Diego Ricardo, has just been murdered in a bar brawl in Buenos Aires, a fact we learn along with Theo (Clive Owen) via a news report displayed in a London cafe.

There's something frighteningly humdrum about this moment. The death of "Baby Diego," who was stabbed after refusing to sign an autograph, feels realistic, the news report sounds like it was ripped straight from the BBC, and the cafe's customers look pretty much entirely ordinary. Even the street outside, which is overflowing with smog, litter, and authoritarian propaganda, hardly seems unthinkable to viewers in the early 2020s. This sense of near-future familiarity only makes the premise of "Children of Men" scarier; the threat posed by a film hits much closer to home when it clearly takes place in your home.

In another morbid mirror of reality, the scene ends with a bomb destroying the cafe that Theo has just left. Screams, alarms, and the ringing of tinnitus all combine into a nightmarish cacophony as the camera moves forward, meeting a survivor and her severed arm along the way. The ringing draws on as the title card appears, leaving you under no illusion as to the kind of film you're about to watch.

The Thing

John Carpenter's "The Thing" was met with a scathing critical reception and a lukewarm box office take when it was released in 1982. This might seem odd today, considering the movie's reappraised status as a horror classic, but I'd like to posit a theory as to how it could have happened: Everybody walked out after the first ten seconds.

For some reason, "The Thing" opens on a ludicrous shot of a UFO careening towards Earth, one that would look out of place on an episode of "Star Trek" because the CGI is, somehow, worse than anything that show put to screen. For the sake of argument, though, let's just pretend this never happened, as the first proper scene in the movie more than deserves its place among the greats. The palpable dread in those stunning shots of the Antarctic landscape only grows as the heartbeat pulse of Ennio Morricone's synth soundtrack quickens. There's even something otherworldly about the Norwegians, who are faceless and silent during their surreal hunt.

That quiet dread gets a whole lot louder once the Norwegian helicopter lands at the American research station. A mishandled grenade and a few gunshots later and the hunters are dead, the helicopter is burning, and the mysterious dog has found some new owners. At first, much like the Americans themselves, you're not really sure what has just happened. Thanks to the efforts of Carpenter and Morricone, though, you're left damn sure that it can't have been good.

WALL-E

Aside from WALL-E and EVE, nobody speaks in "WALL-E" until just under halfway through the movie — but somebody sings long before that. Pixar's sci-fi classic opens on a series of shots of distant planets, stars, and galaxies, all set to "Put on Your Sunday Clothes," a song from the 1969 musical comedy "Hello, Dolly!"

At first, the song's lyrics, which dream of a "world outside of Yonkers" that's "full of shine and full of sparkle," offer a pleasant enough backdrop for this whirlwind tour of the cosmos, but they take on a new meaning as we arrive on Earth. In this eerily prescient future, the planet has been abandoned by mankind, who left nothing behind but refuse and smoke-filled skies. The colorful scenery of deep space gives way to a blanket of dull brown, and, at first, nothing seems to move on the planet's surface. And the music carries on: "Put on your Sunday clothes, there's lots of world out there/Get out the brilliantine and dime cigars/We're gonna find adventure in the evening air/Girls in white in a perfumed night/Where the lights are bright as the stars!"

The contrast between "Put on Your Sunday Clothes" and the visuals of the opening scene of "WALL-E" is so perfect that it's difficult to believe the song wasn't written for the movie. As it is, though, you just have to put it all down to a shrewd creative decision ... and brilliant filmmaking all-round.

District 9

Let's be honest: The apartheid allegory that propels "District 9" is anything but understated. Neill Blomkamp's 2009 feature debut takes place in an alternate version of 1982, when a huge spaceship has arrived over the skies of Johannesburg. The "prawns" who steered it to Earth are taken by the South African government and relocated to District 9, a crime-ridden slum that the local populace exploits and despises. Sounds depressingly familiar, doesn't it? Nevertheless, the opening sequence shows that anything lost in subtlety is more than made up for in sheer horror.

The first scene of "District 9" establishes the film's faux-documentary format and introduces Wikus van de Merwe (Sharlto Copley), a petty bureaucrat charged with monitoring the prawns. It also provides some backstory about the aliens' arrival, as told by journalist Grey Bradnam (Jason Cope), and presents footage of the first contact between humans and prawns. Rather than the "music from heaven" and "bright shining lights" anticipated by one of the other interviewees, the ship's interior is dark, grimy, and filled with emaciated aliens. It's the last thing you'd expect from the gigantic spaceship looming over the city, but the mortified reaction of the humans and the fearful, almost pathetic nature of the prawns really drives home the inequality between these two species, artfully setting up the film's primary conceit. And once the prawns come down and the fences go up, it becomes quite clear where all of this is going.

Galaxy Quest

The opening of "Galaxy Quest" is not particularly bold. It's not beautiful, either, and it's probably only scary if you're an acting coach. It is, however, the perfect introduction to the ropey sets and contrived dialogue of the in-universe "Galaxy Quest" TV show.

This brief glimpse of the movie's "Star Trek" pastiche begins with a shot of a CGI spaceship that rivals that in "The Thing" for its unbridled awfulness. On the bridge, Commander Peter Taggart (Jason Nesmith, but actually Tim Allen) leads his comrades as they attempt to escape a fleet of unknown pursuers. Everything here is terrible in the best possible way, from Alexander Dane's (Alan Rickman) prosthetics to Gwen DeMarco's (Sigourney Weaver) hugely inappropriate costume to the inexplicable inclusion of a small child (Corbin Bleu) on the crew. It's all for the best, though. "Galaxy Quest" is practically built around the imperfect charm of mid-20th century sci-fi television, and this chance to watch the show that started it all serves the rest of the movie well.

At its core, this scene works so well simply because it's really, really funny. Dane's catchphrase ("By Grabthar's hammer!") has become almost as beloved in real-life cult film circles as it has among the fans depicted in the movie, while the episode's reliance on a contrived cliffhanger will be very familiar to anyone who loves '60s sci-fi. And that's to say nothing of Fred's (Tony Shalhoub) woefully misguided attempt to appear as Asian as his character is supposed to be. Sure, it's not exactly "2001," but the first scene in "Galaxy Quest" is still good for a laugh or two.

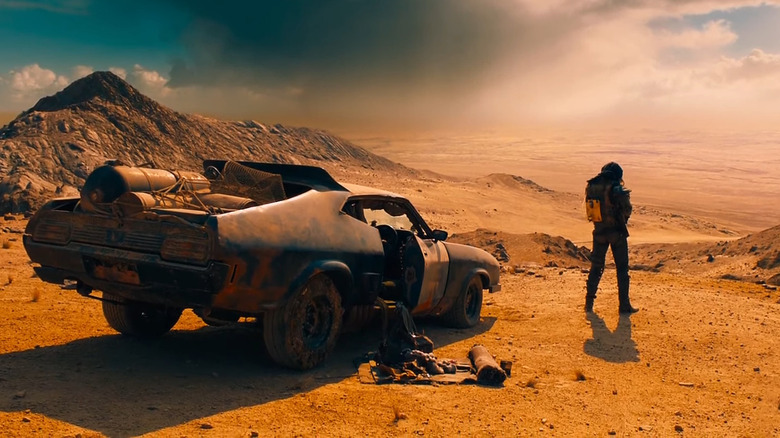

Mad Max: Fury Road

"My name is Max. My world is fire and blood." Those are the first words we hear in "Mad Max: Fury Road," and boy, is Max right. Unless you've been living under a rock in the post-apocalyptic Australian outback, you probably know that "Fury Road" is one of the most daring and exhilarating action movies of all time, and it's definitely fair to say that director George Miller kicks things off with a bang.

Over a series of foreboding soundbites from the end of the world, Max Rockatansky (Tom Hardy) peers into the collective mania that has gripped the few remaining survivors. "As the world fell," he says, "each of us, in our own way, was broken. It was hard to know who was more crazy ... me or everyone else." The following hard cut to Max and his car reveals a sudden and surprising burst of color, effectively screaming that this movie, despite being set entirely in the desert, is going to be more visually impressive than you could ever imagine. Then, of course, there's the chase itself, a brief, chaotic ruckus that results in a stunt crash so utterly phenomenal that lesser movies would save it for their climaxes. Here, it's only a small taste of the havoc to come, but damn — what a taste.