Why Does Skinamarink Look Like That? A Guide To The New Horror Movie's Unique Visual Style

When I first saw the trailer for "Skinamarink" I felt strangely exhilarated. The whole thing looked unreasonably terrifying, but there was something about the visual style that was so intriguing I almost didn't realize how unsettled I was. Its static chiaroscuro and grainy, off-kilter framing gave it this vividly ominous sense, like some cursed home video dredged from a decrepit suburban basement.

Director Kyle Edward Ball's indie horror has since gained significant attention, even before its theatrical release in 2023. Having leaked online due to a technical glitch during its run at the 2022 Fantasia International Film Festival, the film took on an almost mythical aspect, becoming what Variety called, "The internet's new cult obsession." TikTokers and YouTubers alike latched onto Ball's distressing fever dream of a film, posting videos with titles like "Tik Tok Tried To Warn Me About This Movie."

While the trend escalated and its sensationalist language intensified, Ball waited quietly to unleash his movie on a wider audience, thanks to a distribution deal with IFC Midnight (for theaters) and Shudder (for streaming) that remained intact despite the film being pirated. Now, with "Skinamarink" finally creeping out into the wider public, audiences have a chance to witness all its dark, oneiric glory.

Having finally seen it, I can say that while the film is indeed one of the most unsettling things (not just films) I've ever witnessed, my initial fascination with the trailer's visual style has only increased, lingering even more than the primal terror I felt while trying to make it through the runtime without bailing. And so, like so many horror movie victims, I feel compelled to move towards the horror rather than run — to deconstruct the sheer sensory onslaught that is "Skinamarink." Come along with me into the darkness, won't you?

Fear of the unknown

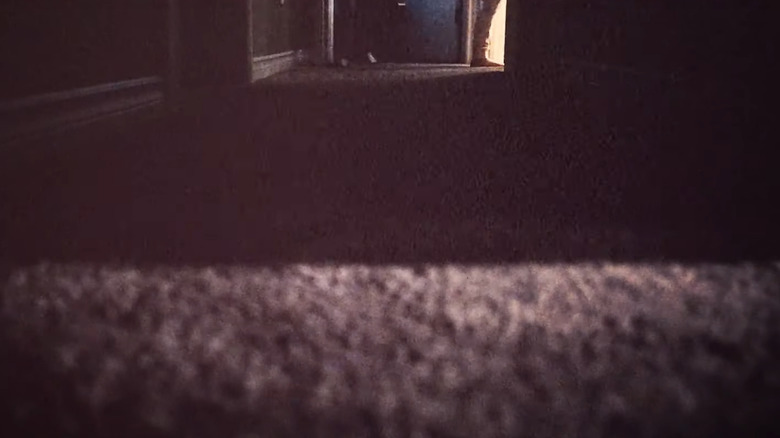

Have you ever watched a horror movie with friends, only to surreptitiously look into the corner of the room for the scariest parts? You don't want to get caught obviously looking away, so you just subtly adjust your vision so the screen is barely visible. Well, imagine a movie where almost every shot is like that. That's "Skinamarink," where most of the action happens just off-screen as if it's just too obscenely horrific to address head-on. Kevin and Kaylee, the two children at the center of the film, awake to find their father missing and the doors and windows of their house vanished. As they explore their newly transmogrified home, the camera frames only their feet, a door frame, or a dimly lit corner of a ceiling.

Kyle Edwards Ball discussed the influence of avant-garde filmmakers such as Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren, but expanded on his approach to framing and shot selection in a RogerEbert.com interview, explaining how, "Consciously, almost every shot is from kid height," — a technique borrowed from Steven Spielberg and Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu. This emphasizes the disorientation, forcing viewers to question whether they're seeing things from, "the kid's perspective" or simply a "shot of the room."

It's an inspired technique that plays on the fear of the unknown. Some studies have claimed fear of the unknown is possibly the fundamental fear. Others have noticed "heightened activity in the amygdala," which points to a possible state of hypervigilance, so that we remain extra aware of potential risks. This is exactly how watching "Skinamarink" feels. We don't really know exactly what's happening because we can't fully see it so we remain hypervigilant throughout, not just trying to predict what's going to happen, but what's actually happening in that moment.

Keeping things practical

There's much more to "Skinamarink" and its intense, surreal style than unusual framing techniques. Shot on location in Kyle Edward Ball's childhood home, which is still owned by his parents, the movie makes use of practical effects throughout. Although most of that was out of necessity, considering the film's minuscule budget, it nonetheless feels so perfectly in keeping with the project's overall lo-fi style.

Ball shot the movie digitally, and gave himself some strict guidelines for lighting. As he told Inverse, he and his director of photography, Jamie McCrae, were only allowed to use practical lights throughout filming, whether that be, flashlights, light emanating from a TV screen, or a household lamp. Generally, scenes were shot in extremely low light, with Ball using a high ISO to help expose the dim images. He then took on the entire edit himself, using intense color grading to enhance shots over the course of his four-month editing process.

In terms of digital effects, Ball used some basic techniques including Photoshopping himself out of frames while holding objects on the ceiling to create the illusion of rooms being upside down. Elsewhere, "Content Aware" editing tools allowed him to easily replace doors and windows with blank spaces. Otherwise, much like the 1970s films from which Ball took so much inspiration, everything was done practically.

Old films and the lo-fi approach

During post-production, Ball drew from his love of older films by adding screen pops and film grain that gave "Skinamarink" its distinct lo-fi feel. Coupled with the static hiss that persists throughout the film, this lo-fi aesthetic goes a long way in making the whole thing seem like some sort of recently unearthed relic from the previous century.

The director spoke about this in his RogerEbert.com interview:

"I always felt that movies from the '70s make me feel differently than movies today do. Movies and cartoons from the '40s, media of different ages, spark something in me, and in other people, that you can't quite put your finger on [...] I didn't just want 'Skinamarink' to look like an old movie. I wanted it to feel and sound like one. I wanted to go really [hard] with that. I didn't just want to make the dialogue sound like it was recorded on an old microphone. I wanted the audio to feel like an old, scratched-up re-taping of a film that wasn't preserved from the '70s."

The lo-fi look adds yet another layer to the dream-like surrealness of "Skinamarink." Even before the grain and degraded filter was added, there's a texture to every frame thanks to Ball's preoccupation with close-up shots of various elements of his childhood home. Rather than push things over the top, the presence of the constantly shifting grain and screen imperfections actually intersect with the way in which "Skinamarink" relies on the viewer's own imagination to create a lot of the horror. Shots lingering on dimly lit hallways already play on our tendency to see things in the dark that aren't there. But with the grain dancing around, it's even easier to imagine all manner of ghastly visions lurking in the shadows.

The liminality of Skinamarink

Everything so far is enough to make "Skinamarink" one of the scariest horror movies of recent years, but there's more. In fact, this is where things get really interesting. Ball was inspired by wider cultural developments and aesthetic sensibilities when working on his movie — one significant example being liminal spaces.

If you spend enough time online, you've likely come across this meme. There's a subreddit dedicated to liminal spaces (a few, in fact), which Ball says played a big part in the development of "Skinamarink." In terms of its popular definition in the context of spaces, "liminality" refers to something that feels like it's partly rooted in reality, and partly rooted in surreality or a dream. It serves as the in-between area for transitions of mental and physical proportions and takes on meaning contingent on who is occupying the space and what the space was created for. In its "about" section, the r/liminalspace subreddit uses a quote from the Cambridge Art Association:

"A liminal space is the time between the 'what was' and the 'next.' It is a place of transition, a season of waiting, and not knowing. Liminal space is where all transformation takes place."

When it comes to the online communities that sprung up around this idea of liminal spaces, the result has been the emergence of a new aesthetic. The whole thing is concerned with locations that are, abandoned and often empty. This could look like a mall in the middle of the night or a school hallway in late July. What's key here is the combination of feelings this evokes: "Slightly unsettling, but also familiar to our minds."

With its close-up investigation of familiar elements of suburban life — a power outlet, the impressions in a carpet — "Skinamarink" relies on familiarity to draw us in while simultaneously unsettling us. In that sense, the film is its own kind of liminal space, which makes sense considering Ball spent time exploring that very subreddit promoting his YouTube channel (more on that later).

Making it weird

Reddit proved invaluable to "Skinamarink" in other ways. Its r/weirdcore subreddit was yet another source of inspiration for Ball, and turned out to be a shared interest between him and McCrae.

The Weirdcore aesthetic is similar to liminal spaces in its leveraging of "familiarity," but is more concerned with a particular design and photographic style from the late '90s to mid-2000s. As the wiki explains it, the style is, "Strongly influenced by the general look and feel of images shared on an older internet," and combines, "Amateur editing, primitive digital graphics, lo-fi photography, and image compression" to create feelings of, "Confusion, disorientation, dread, alienation, and nostalgia."

With "Skinamarink," one of the only pieces of context we're given is that it's set in 1995, which like the Weirdcore aesthetic, plays on the nostalgia of its audience. The whole film, with its CRT TV and the wood paneling of Ball's parents' house, feels like some nightmare '90s nostalgia trip. The threads in the carpet, imperfections in the wall, lego bricks strewn across the hardwood. This is the minutiae of our childhood; tiny fragments of a time when our perception seemed so keenly sensitive. The kind of thing that only resurfaces in dreams. But in "Skinamarink" these are dark recollections that tip nostalgia on its head just like Weirdcore — stripping the sentimentality from nostalgia yet somehow maintaining its longing aspect — give the film this disorienting feeling of being utterly terrifying yet, at times, oddly comforting.

Ultimately that's where the real terror arises, the ending of "Skinamarink" aside. The fact that we've been lured in by these familiar images only to be exposed to something truly evil makes "Skinamarink" feel like a nasty trick, forcing us to walk through a house made of our own decayed childhood memories.

Bitesized nightmares

Beyond emerging online aesthetics, the internet contributed more to why "Skinamarink" feels so nightmarish. And I don't mean in the sense of it being a horrific experience, but in the sense that it actually feels like a dream — some "nocturnal illumination of diabolical origin" to borrow Nabokov's phrase.

For five years before making his film, Ball ran a YouTube channel called "Bitesized Nightmares," where he would solicit recollections of nightmares from viewers and turn them into short films that emphasized atmosphere over storytelling. The result is a channel full of "Skinamarink"-style short films that use the same distorted sound effects and dreamy tone to establish that oddly familiar yet undeniably creepy feeling. Among them is Ball's short, "Heck," which serves as a proof-of-concept for "Skinamarink."

That nightmare element is crucial to the film's success. The sustained hiss is very close to the sound I've personally heard during sleep paralysis episodes, and faintly recalls Gaspar Noé's technique of using an almost imperceptible tone in the background of his film "Irreversible." The sound hovers around the 28hz frequency and allegedly causes "nausea, sickness, and vertigo in humans." In "Skinamarink," the hiss is much more conspicuous, and part of a rich soundscape that almost feels like some sort of twisted ASMR experiment. All of which manages to evoke similarly nauseating internal states, all the while being indebted to YouTube and its thriving avant-garde community. As Ball explained it:

"Shorts are thriving on a place called YouTube. In a lot of ways, people are experimenting with the moving image now more than ever. It was a matter of time before people started taking those experiments and tried transitioning into a feature film."

Substance in style

The fact that these online communities, aesthetic sensibilities, and experimental impulses have collided in "Skinamarink" feels like a seminal moment. Sure, this is a microbudget film which will likely have a limited audience even after its theatrical and streaming release. But it feels bigger. And sure, there have been movies about the modern internet and how it affects those growing up under its influence, such as Jane Schoenbrun's "We're All Going To The World's Fair." But "Skinamarink" feels like it's of the internet — like the cutting-edge conversations and aesthetics evolving online have coalesced into something capable of penetrating and even subverting wider culture.

Rolling Stone called the film "just a feature-length extension of what Ball's YouTube channel already does." But isn't that a pretty incredible thing? A feature-length liminal nightmare experience that eschews complex plotting in favor of stoking some deep-seated primal fears within its viewers. How can you not think of that as something genuinely cool, especially when it's being given a mainstream platform?

The film has been criticized for that very approach, described as having "barely a narrative." And while I don't think that's true, the fact is that its style is enough of a statement in and of itself. You often hear it said that something is "more style than substance," which almost makes "style" sound like a pejorative. But so often, artistic products can make a substantive statement precisely because of their bold, arresting style. There's no better example than "Skinamarink," where Ball's combination of practical and post-production techniques tell their own story of rich cultural underpinnings and radically inescapable, online sensibilities. In that way, there's more than enough story captured within the movie's style than any narrative could possibly contain.