The Oscars Were Created For A Specific Purpose, And It Wasn't Celebrating Film

The Academy Awards aren't just a ceremony where movie stars and filmmakers get little gold statues that honor their work. Over the vast 94-year history of the Oscars, the Academy Awards have taken on a rarefied air. They're a huge annual event that celebrates an industry that gives people entertainment, inspiration, and hope. Those statues that say things like "Best Picture" have become Hollywood's most coveted items, and symbols of greatness within a powerful, influential art form.

Not only that, but the Academy Awards drive so much of the conversation about cinema, with Oscar buzz dominating publications and periodicals for the last several months of each year, and the first several months of the next year. By the time the ceremony finally takes place and the Oscars are handed out, film festivals like Sundance have already got the buzz rolling for the next year's Academy Awards, and the process starts all over again.

Yes, the Oscars are a magical and powerful force.

And to think, they were invented to screw over the very people who won them.

The Oscars have a second name, it's M-A-Y-E-R

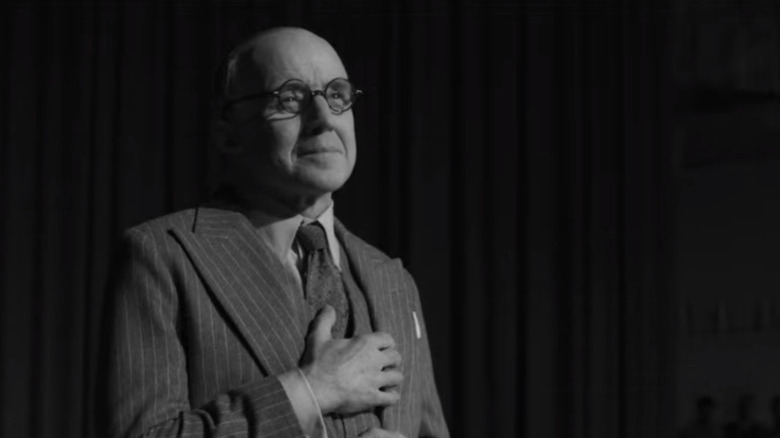

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, known to most as simply "The Academy," was founded in 1927 by studio mogul Louis B. Mayer, who was the head of MGM for 27 years (that second "M" stands for "Mayer") and who was recently played by Arliss Howard in the David Fincher biopic "Mank." But the Academy wasn't founded out of the goodness of Mayer's heart, or out of a fervent desire to reward the finest artistry in the industry. It was founded out of a fervent desire to keep studio talent from unionizing.

As Vanity Fair tells it, Mayer wanted to build a house on Santa Monica beach, and quickly, and he wanted to use round-the-clock studio labor to build it. But under new union contracts — which gave workers set rates and overtime — his plan would have cost a fortune, so he wound up outsourcing most of the work, and also wound up getting worried about how much unions were going to cost the industry over time. If costly above-the-line talent got involved and, you know, got paid what they deserved, Mayer's empire could crumble.

So Mayer spearheaded the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences to manage disputes within the industry. And since the studios created it, this gave them outsized power to control those negotiations and stave off meaningful changes that would benefit studio employees. So, as Scott Eyman wrote in "Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer," the Academy Awards were originally intended to be little more than a distraction, to keep the talent's focus off of their paychecks.

Louis Mayer had a way with b-o-l-o-g-n-a

Sure, the Academy Awards were, on the surface, a way to honor the great work in the industry, starting with celebrated films like "Wings" and "Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans," the first two Best Picture winners (at the first ceremony there were two equal awards for the top honor). But they also gave artists a symbolic token to vie for, which suited Louis B. Mayer just fine.

"I found that the best way to handle [moviemakers] was to hang medals all over them," Mayer is quoted as saying in "Lion of Hollywood." "If I got them cups and awards they'd kill themselves to produce what I wanted. That's why the Academy Award was created."

Mayer's cynical motive for creating the Academy Awards wouldn't dispel unionizing efforts forever. Indeed, the guilds formed relatively quickly. The Screen Actors Guild was created in 1933, in response to pay cuts, The Writers Guild officially became a union in 1933, barely a month after the creation of the Screen Actors Guild, and The Directors Guild was founded in 1936. All of these institutions and more would use the power of collective bargaining in an attempt to protect their respective artists.

Despite all this, Mayer's distractionary tactic did have a lingering effect on the industry. Every year filmmakers spend months of their time campaigning for Academy Awards, while entertainment publications spend months — sometimes all 12 of them — discussing and disseminating which films will be nominated in the future, and/or which of the actual nominees will win, or deserve to. That's time that could be spent pushing more meaningful concerns into the foreground, about the entertainment industry, the art it creates, and the artisans who create them.

But dang it, human beings just like competitions and shiny baubles, don't they?