Quentin Tarantino Disagrees With The Idea That Certain Movies Couldn't Be Made Today

"This movie could never be made today" is an increasingly familiar refrain in our fractious times. As our society grows more diverse, and we reckon with the racism and sexism of less enlightened eras, some crotchety members of the old guard have a tendency to throw up their hands and lament that an assortment of classic films with perceived problematic content would never make it past development in modern Hollywood.

In certain, screamingly obvious cases, this is a very good thing. D.W. Griffith's "The Birth of a Nation," a virulently racist movie that celebrates the Ku Klux Klan's heroic lynching of a freed slave would be a one-way ticket to infamy (or a three-picture deal with The Daily Wire). The mere notion of Walt Disney's "Song of the South" would probably result in the creator being ousted from his own company (and maybe offered a gig as the chief of animation at The Daily Wire). John Hughes' "Sixteen Candles," with its creepy date-rape jokes and wantonly racist depiction of foreign exchange student Long Duk Dong, would've ended the writer-director's studio career (resulting in The Daily Wire's "Planes, Trains and Automobiles" starring Rob Schneider and Robert Davi).

Movies aggressively trafficking in hateful stereotypes do not, thankfully, fare well in today's discourse. Satire, however, is a different matter altogether. It depends on who's telling the joke, but there is still room for a sharply observed comedy about cultural differences and skewed attitudes. Which brings us to the elephant that's refused to leave the room for several decades: could Mel Brooks' "Blazing Saddles" be made today?

Quentin Tarantino has thoughts.

Where is the line in 2023?

In an interview with Deadline timed to the release of his hugely entertaining and plenty infuriating "Cinema Speculation," Tarantino balked at the assertion that certain movies would never make it before cameras now that media has become more culturally diverse, and thus resistant to insensitive portrayals of people less white than Pat Boone. After discussing his reaction to "Blazing Saddles," which he saw during its 1974 theatrical release with his mother and her Black boyfriend (they all thought it was hilarious), and being asked if the culture could bear its take-no-prisoners racial and ethnic humor today, Tarantino told Deadline:

"Well, by asking questions like 'Could that movie be made today,' that's like you're — I don't believe that stuff. Because by putting out that hypothetical, you're kind of suggesting that it couldn't be, and then people just kind of assume that they can't be and then that's what happens."

Tarantino has been a lightning rod in the past due to his repeated use of the n-word in films like "Pulp Fiction," "Jackie Brown," and "Django Unchained." He's been taken to task for this by Spike Lee and defended by Samuel L. Jackson (who's worked with both directors multiple times). He is, to quote the late, great Charlie Murphy, a habitual line-stepper. But a good-faith reading of his work reveals him to be a moral, socially conscious softie at heart. Aside from "Reservoir Dogs" and "The Hateful Eight," he digs happy endings (yes, "Jackie Brown" closes on a melancholy note, but at least our heroes get away clean).

And yet I can't help but feel, in terms of what he can get away with content-wise, he's been grandfathered into the 21st century. If he made "Pulp Fiction" today, as a white man with that screenplay, no matter how brilliant, he'd better be prepared to cast Gina Carano as Mia Wallace. So I'm not sure he's a reliable authority on what can pass cultural muster in 2022.

Maybe we should ask the guy who directed "Blazing Saddles" if "Blazing Saddles" could be made today.

The Camptown Ladies?

In a 2017 interview with the BBC, Mel Brooks sounded a downbeat, if oddly contradictory note about the modern state of comedy:

"It's OK not to hurt the feelings of various tribes and groups," he said. "However, it's not good for comedy. Comedy has to walk a thin line, take risks. It's the lecherous little elf whispering in the king's ear, telling the truth about human behavior."

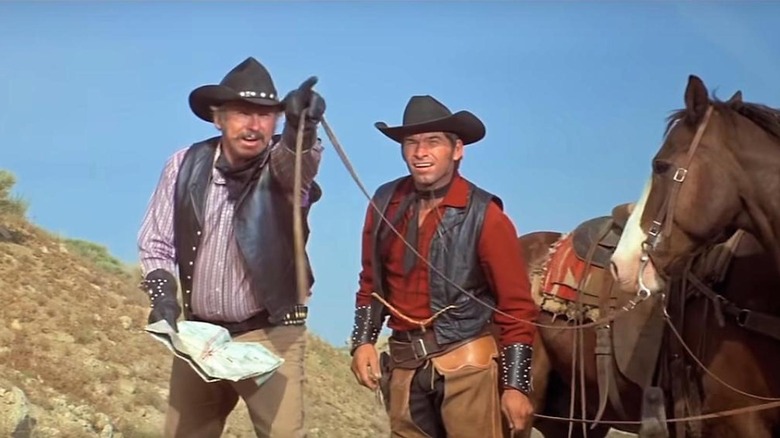

Brooks goes on to say that he would never make light of the Holocaust, but what of slavery? Early in the film, Clevon Little's Bart is forced by the n-bomb-spouting Taggart (Slim Pickens) to propel a handcart down newly laid train rails to find out if there's quicksand ahead. I've watched the film with a racially mixed audience, and everyone howls when Taggert, outraged that his underling wants to use horses to test the firmness of the soil, brusquely tells him to "send over a couple of n******." This line arrives after the Black workers outclass their uncultured overseers by crooning a delectably urbane interpretation of Cole Porter's "I Get a Kick Out of You" as a work song. The white cowboys respond by clownishly belting out "The Camptown Races."

The quicksand scene grows more egregious (and, let's face it, funnier) when Taggert and his men opt to save the handcart instead of Bart and his partner.

We'll work up a number six on 'em!

Brooks and his team of writers, which included Richard Pryor, are lampooning the galling inhumanity of the slave-owner mentality. But what's funny in this context is an accurate representation of how these men and women were treated upon reaching America's shores. They were property, and more disposable than a functioning handcart. There is zero difference between this and the Nazis' view of Jewish people. Then again, perhaps it's not so odd to hear Brooks voice this opinion given that he remade Ernst Lubitsch's "To Be or Not to Be," and 40 years later, completely defanged one of the most provocatively funny films to come out of World War II.

In the realm of satire, "Blazing Saddles" is a unicorn. It's clearly on Bart's side, but Brooks can't help but spend a good deal of time with Harvey Korman's Hedley Lamarr because Korman is unparalleled at portraying a conniving, cold-hearted bastard. Still, we're laughing at the villains and the white townspeople, and we're laughing with Bart. Most importantly, everyone involved is in on the joke, including the audience. That's why the film has endured, while the aforementioned movies are now frowned upon (if not outright shunned, though I do think they should be readily available for educational purposes).

But could it be made today? By a Jewish director with a mostly white writing staff and Richard Pryor? With its incessant use of the n-word? I'd like to think so.

The unifying power of comedy

Film critic Drew McWeeny interviewed Brooks nine years ago for the 40th anniversary of "Blazing Saddles," and told the director that he attended a screening of the film in Westwood on the eve of the second Rodney King verdict. The previous decision incited the 1992 Los Angeles riots, so the fact that this audience was split 50-50 between white people and people of color held the potential to be a powder keg of racial resentment. According to McWeeny, 10 minutes into the movie, every single person in the theater was howling. The pressure dissipated, and everyone reveled in a comedy that sent up the stupidity of racism while, as Brooks once said of his movies, rising below vulgarity. Unbeknownst to McWeeny, Brooks was there that evening, and said this:

"It was like Columbus seeing the New World. It was like this movie audience saw the New World of cinema for the first time, and they really celebrated the s*** out of it. They went nuts. It was probably, as far as watching one of my movies, you know, on screen, it was probably the greatest night of my life."

Firstly, don't get worked up over the problematic Columbus comment because we know Brooks is an educated man and a humanitarian; the New World is a cliched reference that was de rigueur throughout the 96-year-old filmmaker's childhood. Secondly, white people and their fear of Black people is the entire basis of Brooks' satire, and a racially mixed group of moviegoers roared in unison at the stupidity of this notion.

Could "Blazing Saddles" be made today? No. It already exists. Thank god. And it's as brilliant and essential today as it's ever been.