What Babylon And Paul Thomas Anderson's Boogie Nights Have In Common — And How They Go In Totally Separate Directions

This post contains major spoilers for "Babylon" and "Boogie Nights."

Damien Chazelle's newest film, "Babylon," might be one of his biggest swings to date. After his trip to the Moon in "First Man," Chazelle is back in his element, once again telling a story of ambitious dreamers making their way through a beautiful depiction of Hollywood. However, Chazelle crucially takes a big step away from his cleaner image, characterizing 1920s Hollywood through cocaine, chaos, bodily fluids and scandal. The opening scenes of "Babylon" make it definitively clear to the audience that we're not in "La La Land" anymore.

Despite finding himself in edgier, darker territory, Chazelle's reverence for the medium of film and the artists that came before him are as clear as day. Like Chazelle's other films, "Babylon" is a hodgepodge of different influences and inspirations, from a perversion of "Singin' in the Rain," to the ironic amounts of excess in Martin Scorsese's "The Wolf of Wall Street." If you're a fan of Paul Thomas Anderson, you might have picked up on just how much "Babylon" borrows structurally from Anderson's breakout film, "Boogie Nights."

The parallels are abundant — an introductory long take of an epic party that slowly introduces our entire ensemble cast of characters, a midpoint shift in technology with drastic changes, and even a tribute to Alfred Molina's iconic epilogue as an eccentric drug lord paralleled here by Tobey Maguire. It's obvious why Chazelle would want to pull from Anderson's classic; "Babylon" and "Boogie Nights" are both movies about movies, chronicling the changing tides of their respective industries. What Chazelle's film lacks, however, is a certain amount of respect and empathy for his characters and their lifestyles that makes "Boogie Nights" a special and uniquely transgressive work of art.

Drugs, sex, and the pursuit of great art

In his fourth feature, Chazelle feels at his most jaded. His undying love for the artistic medium of film finds itself clashing with the exploitation and corruption he's experienced in the film industry. It turns "Babylon" into a film of contradictions, embodying an aesthetic that's equally crass as it is luxurious. Chazelle's regular composer Justin Hurwitz orchestrates infectiously rhythmic Jazz pieces that make the party sequences truly come to life. However, the Hollywood glamor is all juxtaposed with displays of debauchery. Chazelle seeks to destroy the sacred veil of Hollywood by emphasizing the drugs and kinky sex as symbols of depravity.

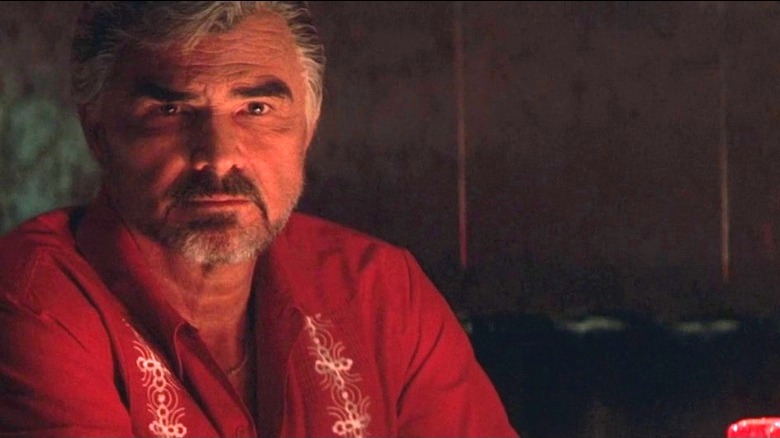

In "Boogie Nights," Anderson is also fascinated by the entertainment industry — albeit a side of it that is much more marked by taboo. In Anderson's examination of the porn industry in the 1970s, he portrays what Chazelle presents to us as "debaucherous" with a refreshing kind of casualty. Anderson depicts hard drugs and explicit sex as a simple reality of his character's lifestyles, but there's no inherent moral value attached to it. The ensemble cast of "Boogie Nights," despite their successes and wealth found within their industry, are still underdogs ostracized from the rest of conservative American society. They might be creating what is deemed as "low" or "degrading," but Dirk Diggler (Mark Wahlberg) and Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds) are set out to do exactly what Chazelle's good hearted characters also aspire to accomplish: make real art.

In "Babylon," our stars Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie), Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt), and Manny Torres (Diego Calva) however, seem to be firmly on the path of damnation after the alcohol and money runs dry and talkies take over the business.

PTA's non-judgemental character study

That's not to say Anderson doesn't understand the intersections between porn and exploitation (the third act shifts into violence serve as a reality call amongst the disco), but his narrative priorities are focused on his ensemble characters' unique bond. Their "shameful" positions in society and the wild party lifestyles they lead are their connective force. It keeps his cast of misfits together as one big family.

There's a refreshing lack of judgment towards the more abrasive sides of these characters and an admiration of their inner souls. One of the strongest examples is Amber Waves (Julianne Moore), a porn star and mother who is robbed of her ability to reach out to her own blood children, but shows her nurturing side through taking care of her community. Amber is especially a motherly figure to young Roller Girl (Heather Graham), whom she even encourages to finish her high school G.E.D. by the end of the film. These characters are rightfully shown as victims of circumstance, but are also portrayed as dynamic humans outside of their social status.

In contrast to Anderson's sympathetic treatment, Nellie LaRoy's (Margot Robbie) tragic journey in "Babylon" feels particularly regressive. Nellie was born a natural star; her first time on a set is a direct parallel to Dirk Diggler's first ever shoot in "Boogie Nights." Though her ability to cry on command is what truly gets her ahead of other actresses of her caliber, Nellie forges a career out of a hypersexual celebrity persona that launches her into fame. Loosely based on real silent-film star Clara Bow, "Babylon" only superficially hints into Nellie's childhood traumas, destructive impulses, and desire to be loved. The result is a character whose dark fate is thematically fitting but feels vapid and cruel.

Edge for the sake of edge

Throughout "Babylon," we watch Nellie carelessly dance with child-like whimsy, do countless lines of coke, gamble, and irreverently make scandalous headlines. When the silent film era comes to a crash and burn, and Nellie is forced to recreate herself due to the rapid popularization of talkie pictures, Manny, now a hot-shot producer, guides Nellie to a prim and proper, rehabilitated image to match the new fancy side of Hollywood elite (which includes severing her romantic ties to Lady Fay Zhu). Though Chazelle certainly shows contempt for the prudish upper echelons that are forcing Nellie into a box, it makes the previous moments of pearl clutching and gawking at her party animal behavior feel all too hypocritical.

Eventually, that "wild child” side of Nellie becomes her and Manny's undoing. After finding herself in a massive debt owed to eccentric kingpin James McKay (Tobey Maguire), she reaches out to Manny for help. Although reluctant at first, Manny decides to look towards his crew for financial assistance and unknowingly takes on prop money to exchange for Nellie's safety. This is a clear homage to the scene in "Boogie Nights," where Dirk and company sell fake cocaine to wildcard gangster Rahad Jackson, famously portrayed by Alfred Molina.

Chazelle, a fan of extravagant finales, decides to take this one step further by having James show Manny and his crew the "a****** of Los Angeles," a shady underground den of orgies, alligators, and a buff man being paid to eat live rats for spectacle. In an attempt of a maximalist portrayal of Hollywood's most repugnant criminal underground, Chazelle makes horror out of disabled, dwarf bodies and fetish aesthetics. James and his gang of deviants are far from pure people, but the way Chazelle conveys their depravity feels tasteless.

Babylon leaves its characters in the dust

Manny narrowly escapes James' gang and returns to Nellie, begging her to run away with him to Mexico and leave show business behind. Still the impulsive character we've seen throughout the film, she feels that her heart belongs in Los Angeles. Nellie dances and disappears off into the night while Manny tries to gather his possessions. In a montage of newspaper headlines, we learn Nellie was found dead at age 34, following the death toll of Jack Conrad's suicide from the scene preceding it. The third act tonal shift in "Babylon" emulates Little Bill's (William H Macy's) suicide in Anderson's film, but crucially, there's no space for Chazelle's characters to reach a proper end point.

There's a frustrating lack of depth to Nellie's story, failing to contextualize her self-destructive path to obscurity and only briefly hinting at her inner psychology. It's disappointing to see from Chazelle, who has always been good at expressing his characters' burning passions and ambitions. "Babylon" is Chazelle's largest scaled film, but he becomes too obsessed with the film's scope that he abandons the pathos that has always made his movies feel like true epics in themselves. The film doesn't just fail Nellie, but also all the characters that have significantly less screen time than her, such as Li Jun Li's Lady Fay Zhu and Jovan Adepo's Sidney Palmer, who represent the margins of the entertainment industry.

One of the most common critiques of Chazelle as an artist is his dependency on homage. I don't find this to be an inherent problem — all modern directors are in some way riffing on what they love, including our greatest — but Chazelle's particular, misguided remix on the beats of Anderson's "Boogie Nights" in "Babylon" reveals a lack of understanding of the source material.

The end of two eras

With his explosive, grand finale sequence, Chazelle begs the audience to see that despite all the pain and suffering that goes into the act of creation, movies are a transcendent good. There's a distinct modernism to the film's production and costume design that never feels like it's setd in the 1920s, but that's because "Babylon" is making a larger connection. The death of the silent film era is not unlike the current state of the theater industry. Despite the slight hope that cinema will always reinvent itself and evolve, Chazelle's ending is brimming with defeatism.

"Boogie Nights" similarly tracks the end of an era: the transition from film to digital videotape in the porn industry. The barrier of entry is lowered, and it briefly changes everything for our ragtag family of provocateurs. With his lack of relevance, Dirk is forced to sell his body. Still the child who ran away from home at the beginning of the film, he finds his way back to Jack Horner, who has been forced to sacrifice his "auteurist" reputation to stay afloat. Roller Girl struggles to get her degree, and while Buck (Don Cheadle) and his wife Jessie (Melora Walters) have started their own business and life together, it has been forever tied to a bloody deed.

Despite all the excess and hedonism, Anderson's film is still full of heart. Whether or not "Boogie Nights" ends on a happy note is debatable. In a sense, the status quo has not totally changed. But, this family of outsiders have endured through the storm and the art they created together still matters. "Boogie Nights" doesn't feel a need to punish these characters or make judgements on the art they create, and that is its greatest, enduring quality.