Why Chainsaw Man's Producers Wanted A First Time Director For The Anime

"Chainsaw Man" was a challenge to adapt from the very beginning. Not just because of its violence and sexual content, but because of its many faces. Sometimes the series is a knowingly stupid action thriller. At other times, it's a bittersweet coming-of-age tale, a skin-crawling horror story, a commentary on labor under late capitalism, and a heartfelt ode to bad movies. The protagonist Denji is an aspirational everyman who fights devils with chainsaws, but he's also a sadboy whose pitiful dreams are easily manipulated. Rather than simply alternating between comedy, horror, and tragedy, creator Tatsuki Fujimoto blends them so that the reader is constantly pulled in whatever direction they least expect. He's the young comics equivalent of Bong Joon-ho, if Bong had a deep love of SYFY schlock like "Sharknado."

Adapting "Chainsaw Man" required threading together these contradictory impulses, while simultaneously transforming the material so that it worked on screen. Not to mention working within the limitations of modern anime's tight scheduling and overproduction. A "Chainsaw Man" anime could be a fiasco, but could also be a once-in-a-generation cultural moment for the anime industry. Yet rather than pick a director who already knew the ropes, studio MAPPA wanted new blood. "We needed somebody else, something new," said MAPPA CEO Manabu Otsuka to Crunchyroll News, "in order to get this sort of bursting raw energy out of the story." They picked Ryū Nakayama.

Copycat

Nakayama had previously worked on MAPPA's last hit adaptation of a Shonen Jump property, "Jujustu Kaisen." The series became a success on its airing in 2020 due to its stylish characters, exciting action sequences, and two great opening animations by animator Shingo Yamashita. Nakayama directed the 19th episode, which featured some of the show's best fight animation. Animation producer Keisuke Seshimo thought that rewarding Nakayama's efforts with a shot at the next big Shonen Jump series made sense. After all, Fujimoto himself called "Chainsaw Man" "a copycat of 'Dorohedoro' and 'Jujutsu Kaisen.'" Seshimo convinced Otsuka to give Nakayama the job, and the rest is history.

It's worth pointing out that despite its surface-level similarities, "Chainsaw Man" isn't much like "Jujutsu Kaisen" at all. The latter series breaks from Shonen Jump convention in some respects, such as its grungy aesthetic and its willingness to let its female cast do things. (In Shonen Jump, the bar is on the floor.) At its heart, though, "Jujutsu Kaisen" is supernatural action boilerplate with likable characters and good art. It's an anime adaptation that preserved artist Gege Akutami's sense of style but cut corners in art direction and compositing. This wouldn't fly in adapting "Chainsaw Man," a series where little details matter a lot. The best sequences in the comic don't just push the boundaries of Shonen Jump, but bend if not break the story's unwritten rules. A good adaptation would need to match that puckish spirit rather than drain it away.

'raison d'etre'

Ryū Nakayama had a career in anime before even "Jujutsu Kaisen." His credits include key animation for projects like "One Punch Man" and "Space Dandy," watering holes for many of his generation's best animators. His closest ties in the anime industry may be to Tatsuya Yoshihara, a champion of digital "webgen" animation. Nakayama boarded the action in the fourth episode of "Yatterman Night," Yoshihara's ambitious if uneven reboot of the "Yatterman" franchise. (The show's opening credits remain an all-time great.) Later, when Yoshihara was chosen to direct the Shonen Jump series "Black Clover," Nakayama not only pitched in key animation for a number of episodes but even handled the whole first ending sequence by himself. When Nakayama was chosen to direct "Chainsaw Man," Yoshihara was hired soon after to serve as action director. Nakayama and Yoshihara's involvement signaled from the jump that "Chainsaw Man" was to be led by young animators, who livened up "Black Clover" despite dire circumstances.

My personal favorite work by Nakayama is "raison d'etre," an animated music video by EVE. Featuring designs by Mai Yoneyama and 7ZEL, it's a delicate slice of urban ennui with a side of fun, surreal action sequences. EVE's signature apocalyptic cityscapes and adolescent emotions are rendered with tact and flair. There are more explosive collaborations in EVE's catalog, such as "How to Eat Life" and "promise." But there's a simplicity to "raison d'etre" that I admire. Its urban landscapes evoke twilight unease but remain tethered to grungy reality. The protagonist's personal struggle is resolved through self-acceptance rather than self-flagellation. The video has stuck with me since I first saw it, though my love of Mai Yoneyama's designs may have something to do with that. (A few years later, she would head her own EVE video.)

A sense of realism

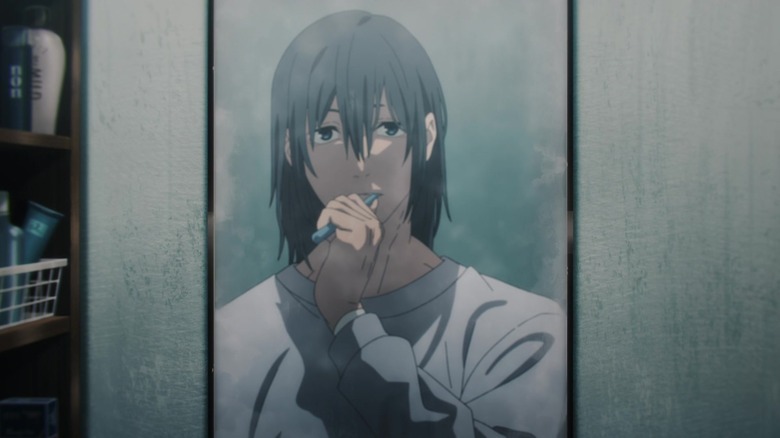

The anime adaptation of "Chainsaw Man" shares some of the strengths of "raison d'etre." The first episode, which Nakayama directed and storyboarded, zeroes in on the relationship between Denji and his chainsaw dog Pochita. Later episodes flesh out the source material by giving characters additional room to breathe. One of the best sequences in the series follows Aki's daily routine after a big fight in episode 4, granting him a moment of peace he never receives in the source material.

His work partner Himeno is similarly given moments to shine in later episodes, including an ambitious sequence shot from her drunken perspective in episode 8. These choices meant that certain scenes from the manga, such as an early confrontation with the Muscle Devil, had to be cut. But I appreciate that Nakayama's team devoted so much time and energy to capturing each character's nuances.

In a MangaPlus interview, comics artist Yuji Kaku (who was once Fujimoto's assistant) discusses Fujimoto's characteristics as an artist and storyteller. "It's not enough to simply be different," he said. "It's necessary to have a sense of 'realism' that makes you think that the world really exists." The creators of the "Chainsaw Man" anime chose to drill down into this aspect. Each character is rendered as a flesh and blood actor rather than a cartoon character. It's an approach that channels the appeal of David Fincher films and American prestige television rather than the bombast of Shonen Jump anime. Kensuke Ushio's score similarly prioritizes uncanny vibes over soaring anthems.

A kiss with barf

But realism is not the sole quality distinguishing Fujimoto's comics. Even more essential are their emphasis on humor. Says Yuji Kaku, "the core of Fujimoto-sensei's work is the structure where the gag element of a character is the driving force of the story." Gags are at the heart of many of the best characters in "Chainsaw Man." One of my personal favorites is Kobeni, whose survival in the face of neverending slaughter and death is one of the comic's best running jokes. Denji himself embodies the tug-of-war between hilarity and seriousness. His dreams stem from adolescent longing, but Fujimoto goes out of his way to spike his little victories (like his first kiss) with rude jokes (an adult woman vomiting into his mouth.) This is why a director like Bong Joon-ho is a better model for Fujimoto's sensibilities than the comparatively humorless Fincher.

The most controversial aspect of the "Chainsaw Man" adaptation is that it suppresses the source material's gag sensibilities. Ryū Nakayama and his staff chose to focus on the comic's cinematic aspects while toning down its jokes and formal experimentation. This had the benefit of making the series more accessible to new audiences, who might otherwise be turned away by the comic's B-movie affectations.

It also unavoidably flattens that material, reducing it to something smaller than the source. It is a very different approach than the one taken by "Mob Psycho 100," which aired its final season this year. "Mob Psycho 100" proved that an anime adaptation could magnify the appeal of the source through addition rather than subtraction. Its many brilliant embellishments heighten what was already there. A cynic might say that the adaptation of "Chainsaw Man" cut away its punk spirit to ensure a marketable hit.

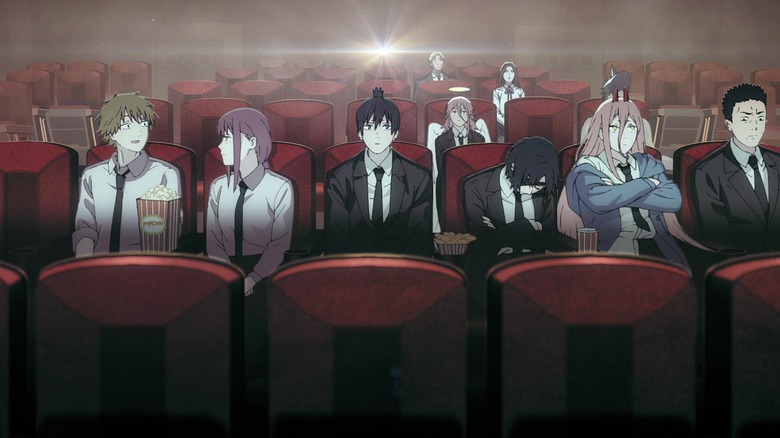

Bow to me, for I am Power

In a piece on Sakugablog, Kevin Cirugeda discusses the contradictions of the "Chainsaw Man" adaptation. The director's cinematic approach, he higlights, meant to highlight Fujimoto's love of movies, happened to overlap with a producer whose inclinations were "to stop the show from becoming too extreme and peculiar." The results are undeniably polished but lack the creativity present in contemporaries like "Mob" or Fall 2022's sleeper hit "Bocchi the Rock." The big exception are the show's opening and ending credits sequences, which are universally beloved. The ending credits especially vary in style and substance, from heavy metal bombast to nostalgia exercises to charmingly indie animations. The best of them, like episode 5's "In the Back Room" headed by Hiromatsu Shu, are as committed as the source material to giving audiences something they've never seen before.

Some have asked, why can't the main body of the series keep the same willingness to experiment as the ending credits? Could it be that Nakayama is holding the show back from its full potential? Not so fast. As Cirugeda reminds us, it was Nakayama who committed to the great range of ending sequences in the first place. While he's committed to his vision of the series, he's also "willing to balance it out with [...] stylized sequences that capture qualities from the original in a more direct way." His connections opened the door to countless talented folks so that they might make their mark in the biggest anime of 2022.

A beautiful star

When discussing the "Chainsaw Man" anime, Nakayama can't help but be overshadowed by his collaborators on the series. My favorite episode is the eighth, storyboarded by Shōta Goshozono; his uncompromising ambition and sense of scale are a perfect fit for the comic's first big turning point. Nakayama's mentor Tatsuya Yoshihara proves his comedy bona fides in the excellent fourth and tenth episodes. Shingo Yamashita, who handled the opening credits, captures the full appeal of Fujimoto's original comic in just a minute and a half. Demon designer Kiyotaka Oshiyama, one of those idiosyncratic geniuses the anime industry has no idea what to do with, drew a commemorative illustration for the series that better captures the energy of the source than the anime ever did.

Even so, I'm probably underestimating Ryū Nakayama. At 32 years of age, he endured unimaginable pressure to direct an expensive and ambitious television series under the thumb of a notoriously difficult studio. Nakayama's crew treated "Chainsaw Man" with care, and even made space for the source comic's wild excesses at the fringes of the series. I fully believe they understand the strengths and weaknesses of the source, and how to leverage that for best effect on screen.

That said: the next stage of the anime will adapt material that, to me, elevates the series from an enjoyable read to an all-time classic. I'm curious to see what choices Nakayama and his crew will make. The results will determine whether the anime is remembered as a worthy translation of the source to the screen, or as a grim reminder that the modern anime industry is even more aesthetically conservative than Shonen Jump.