Cutting The Trailers For Full Metal Jacket Became A Bitter Battle Against Stanley Kubrick

After Stanley Kubrick died, his widow Christiane reflected on a lesson her late husband never quite seemed to learn. As she told the BFI, "He would start the longest and most difficult jobs with this optimism and say, 'Oh, it won't take long.' He never learned the lesson that it does." Kubrick's movies were, themselves, very often the "longest and most difficult jobs" and 1987's "Full Metal Jacket" remains one of the best examples.

As Kubrick's daughter, Anya, offered in that same interview, "The point was to get things right. So if he felt someone was in error, he would make his point." Often making that point would take the form of demanding an inhuman amount of takes on his movies, most famously 60, and in one case 127 takes, of scenes in "The Shining". Seven years after the 1980 adaptation of the Stephen King novel, Kubrick's follow-up, "Full Metal Jacket," would prove that little had changed when it came to the auteur's method for "getting things right."

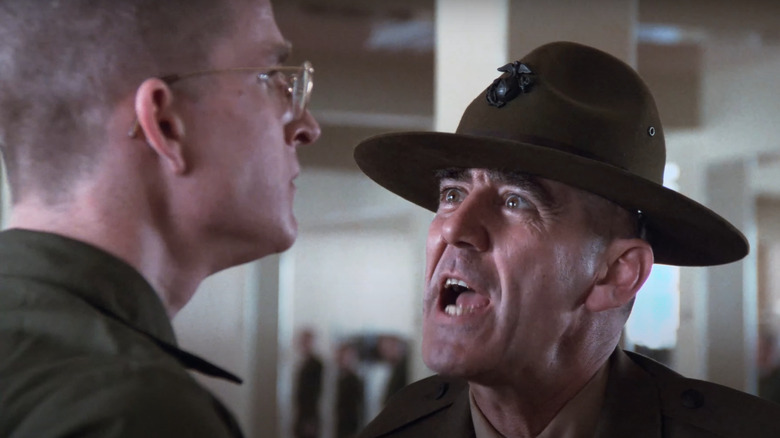

When Vincent D'Onofrio was offered the role of Private Leonard "Gomer Pyle" and flew to England to shoot, he witnessed the director once again forcing ungodly amounts of takes when scenes weren't meeting his expectations. As the actor recalled, Kubrick once "had one actor do two days worth of takes" and would use a megaphone to bluntly announce "'erm it's take er... 72 erm that's just no f****** good, let's go to take 73.'" But the relentless pursuit of perfection didn't end once the scenes had been shot or even after the movie had been edited. No, once he'd meted out his unique brand of directorial perfectionism on-set, Kubrick turned it on the poor guy who did the trailer voice-over.

The smooth voice that sold Full Metal Jacket

Despite his family's protestations that their father and husband was simply a "negotiator" who knew how to effectively communicate what he wanted, it's clear that Stanley Kubrick's perfectionism often spilled over into dangerous conduct. It's well-known how he essentially emotionally abused Shelley Duvall on the set of "The Shining." While he didn't quite take things as far as giving the "Full Metal Jacket" trailer voice-over artist an anxiety attack, it sounds like he was willing to take it there if he needed to.

Kerry Shale is a Canadian actor and voice-over artist with, according to a quote on his website from The Guardian, "A voice so smooth he could sell prophylactics to the Pope." Kubrick evidently felt similarly and wanted to harness that smooth tone to sell his own unholy goods to the masses. Having completed his Vietnam War drama, it had come time to cut the trailers together, and according to John Baxter's biography, Kubrick brought Shale out to his Hertfordshire country home to record.

As Shale recalled, this was highly unusual for a couple of reasons. Voice-over recordings usually took the form of hour-long sessions in a Soho studio where the director would almost always be absent. Here, the actor was being ferried directly to the director to record for what would become hours at his stately manor in the countryside. Unfortunately, things would get even more unusual from there, eventually verging into the sort of questionable territory that Kubrick often traversed.

Kubrick's post-production perfectionism

Shooting "Full Metal Jacket" had already been a monumental task that the near-60-year-old Kubrick seemed to struggle with. But the director was apparently determined to make post-production similarly monumental by asking Kerry Shale to do 40 takes of just the test recording for the US trailer. The voice-over artist would become intimately familiar with the line, "Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket, Coming in June to a theater near you." And that was before Kubrick asked him to record some background voices for a scene in the film.

As Shale recalled, "Normally one gets paid extra for that sort of thing, but I told myself I would dine off this for years." As John Baxter's biography notes, at the time voice-over work was generally paid at £120 a session for a test, and £140 a session once he'd got the job. Repeated recording sessions would often allow voice-over artists to make a lot more once the job was done. But Shale couldn't enjoy any of that until his agent and Kubrick's team had worked out a deal.

That didn't stop the director from bringing Shale to his home for repeated recording sessions. The actor noted in an interview 33 years later: "This went on for weeks, not every day, but usually once a week or maybe twice a week I was always called in the evening, my agent was never called, and I would be out there at midnight." Shale would relive the whole experience in his radio drama titled "The Kubrick Test" in 2020, which retells the story of how Kubrick basically treated him much like many of the actors who'd been subjected to his grueling take demands in the actual film.

'Tell him to call my agent'

During his time with Stanley Kubrick, Kerry Shale would have to re-record lines that he claims the director would "rewrite slightly," generally doing about 40 takes at a time "with no direction whatsoever." Over multiple weeks, the actor says that Kubrick "broke [him] down, which was his way of working." Once, Shale agreed to visit despite initially resisting due to his voice being tired after a day of work and an evening spent partying. According to the actor, Kubrick heard his worn voice and immediately sent him back home.

After that, Shale refused to return, but Kubrick insisted he be brought back to record for the "North American release." For one last time, Shale traveled up to Hertfordshire — near the location where much of "Full Metal Jacket" was filmed — to provide his 40 takes and was told that he would soon be needed for the British trailers. As he recalls it:

"Three or four months later, Leon [Kubrick's assistant] rang and left a message on my answerphone: 'Stanley wants you to do the British trailers. It's urgent. Please call back.' I didn't call. The next morning he rang again, but I was in the bath. My girlfriend answered, and Leon asked her to get me out of the bath. I refused, and said, 'Tell him to call my agent.' That was the last I ever heard."

Some time after "Full Metal Jacket" debuted, Shale's agent got a call from someone in Kubrick's office who, according to John Baxter's book, claimed Shale had "agreed to do all the recordings for his test fee alone," and offered £120 a session. The actor considered launching a court battle but ended up begrudgingly taking a settlement of £1,000.

'Understanding him made me realize what he was doing'

It took some time for Kerry Shale to get over the whole experience. As he said in his interview promoting "The Kubrick Test":

"It took over 30 years to write [the play] because I was actually left quite bruised by the experience [...] Eventually I did a lot of research into Kubrick and got to understand him better than I could have possibly understood him at the time and understanding him made me realize what he was doing."

What was Kubrick doing? It's hard to say. He apparently offered no real direction between takes and was seemingly on a mission "get things right," as his daughter would put it, without providing guidance on how to do that. His questionable conduct over Shale's pay was also eerily reminiscent of a less-than-honest contract trick Kubrick had used some years earlier.

Is this proof that the stories of Kubrick's sinister nature are all true? Not really. But it calls into question his family's assertion that he wasn't obsessive and was in fact "a negotiator of the first order" who "argued his point and often won." In this case, he didn't seem to argue any point at all, preferring to let Shale question his own choices between readings and provide little to no feedback. Even Vincent D'Onofrio claimed that the only feedback he'd provide on-set went along the lines of, "'Just do it better. That was not right, do it better' [...] 'you're f****** up.'"

You can't really argue with the outcome. There's a reason Kubrick and his films are held in such high regard. But you can, and should, argue with the method if only to try to help ensure no other actors endure the Shelley Duvall, and to a lesser extent Shale experience, again.