Spike Lee And Ernest Dickerson Didn't Want Do The Right Thing To Feel Like A Documentary

For such a complex and troubling film, Spike Lee's 1989 film "Do The Right Thing" has a simple premise. On the hottest day of the year, in Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, tensions escalate to an unbelievable degree. Its citizens' sense of community is fractured over the course of the day as small incidents stack up, gradually building to an unforgettable climax set at a pizzeria that has seen it all. And the imagery that follows is burned into the mind of every viewer — the heat felt in every sweaty close-up throughout the movie explodes into a fiery intensity.

In some ways, "Do The Right Thing" has a reputation for grit, for telling an honest story set in a predominantly Black American neighborhood, where every racial group has issues with every other racial group. The racial enmity is chaotic, all-encompassing, such that even the most likable characters in the movie express hostility towards their neighbors when the moment calls for it. The movie may be honest, but it's not gritty or filmed with realism in mind.

Instead, it's deeply expressionistic, with every piece of it geared towards exploring the chaotic structures governing the characters. That goes for the writing, with its bold characterization and rhythmic, symbolically loaded dialogue ("...and that's the double truth, Ruth!"), as well as the set design, which Lee had wanted to send a message.

It also goes for the work of Ernest Dickerson, who was the cinematographer for the film. For him and Lee, the best course of action for the movie was to treat it not as a documentary, even as it dealt with real social issues, but as an expressive piece.

Learning on the job

"Do The Right Thing" was on the horizon by the time Spike Lee had established his name and reputation as a rising filmmaker. In telling this particular story, he would have an ally who had already helped him to build and refine his unique and direct visual style.

"We were trying things out, learning on the job, and getting paid for it" is how Ernest Dickerson described his early collaborations with Spike Lee to the Chicago Reader. The two had met while attending film school at NYU, and Lee was taken with Dickerson's obvious talent as well as their shared love of classic film, an aesthetic that would become a touchstone for their collaborations. In "Do The Right Thing," the opening credits were directly inspired by the 1963 musical "Bye Bye Birdie," per Slate.

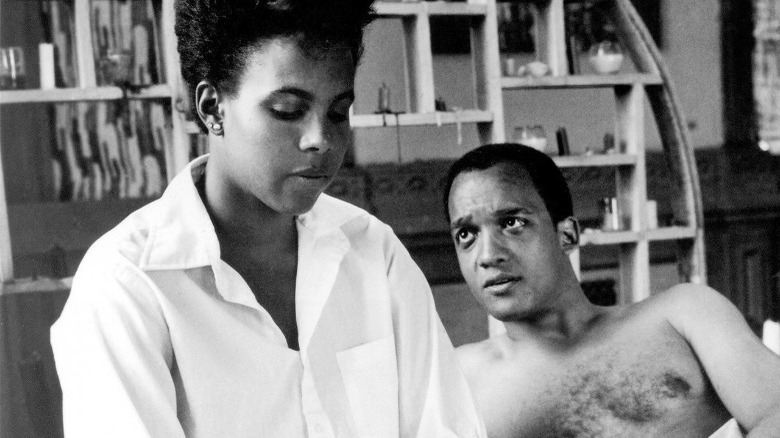

Besides helping Lee with his student films, Dickerson also shot his debut feature, "She's Gotta Have It," and for a relatively low-budget black-and-white drama, it's got visual flare and dynamism to outclass most movies. Even if it features one of Spike Lee's most regrettable narrative decisions, the movie shimmers thanks to Dickerson's magnificent work. And it was a far cry from Dickerson's first feature gig, on John Sayles' 1984 film, "The Brother From Another Planet."

Even given Lee's 1988 HBCU musical "School Daze," "Do The Right Thing" would be something new for both of them. "School Daze" was a color film, highly stylized around its central performances and college drama. But "Do The Right Thing," dealing with a low-key story about a pizza delivery guy on a fateful day, would be something different: expressionistic but unmistakably set in the real world.

Heatwaves and Jack Cardiff

To treat the story as seriously as possible meant constructing a new look using old techniques. And the focus had to be on the heat. The story of "Do The Right Thing" doesn't work without it. The collective feelings of the movie's Bed-Stuy residents are catalyzed by punishing New York summer heat. Heat that makes kids want to crack open fire hydrants and heat that makes everyone else miserable. Heat that leads to tragedy. Ernest Dickerson told The Guardian that the movie's original title was "Heatwave," which would have been perfect if not for its actual eventual title.

Dickerson was lucky enough to have more preparation time on "Do The Right Thing" than ever before. Because of that, he began working with the production design team to make sure there was little in the way of cool colors on the blue end of the spectrum. As he told the Chicago Reader, everything "was geared towards earth tones and warmer colors." The interiors of the brownstones and Sal's (Danny Aiello) pizzeria all fit into that.

Golden light blazes through the windows and onto the streets, another trick Dickerson picked up studying older films. Where their contemporaries in the industry had taken to using HMI lights, Dickerson and Lee used "old-fashioned arc lights" to get the intensity they wanted. They studied the cinematography of Jack Cardiff, who gave 1947's "Black Narcissus" its stunning visuals. And they looked at Carol Reed's masterful thriller "The Third Man," with its canted angles and heavy shadows.

More than anything, Dickerson told Zavvi, they wanted it to be "more immersive."

Filming fires

The end result was one of Spike Lee's best movies, immersive and enveloping, a whole world on its own, which was no accident. It was the result of the movie's cost-limited production, where they really only had about a block's worth of exteriors on which to film. "For a while, it was a real living, breathing community," cinematographer Ernest Dickerson told The Guardian, as all the actors would be hanging out on set even if they weren't the focus, for all eight weeks of production.

But as emotionally gripping as it is, and laid-back and observant it can be, "Do The Right Thing" is a movie that never tries to mimic the feeling of a documentary. There's a beautiful sense of artifice to its look, one that came just as much from classic cinema as from Spike Lee's experiences in Bed-Stuy. It's an unreality that complements and emboldens the real, difficult challenges faced by the community.

That became difficult when it came to the movie's climax, a busy and complicated riot sequence that ties the movie's various threads together. Per The Hollywood Reporter, Dickerson was entrusted with storyboarding the scene and documenting the chaos, but keeping it in the visual style of the rest of the movie. Because Lee had other matters to attend to, Dickerson extensively plotted the coverage. What they got in the movie feels less like a real fire than something divine — a fitting finale to a movie of such unique beauty.