The Outlaw Controversy Explained: Howard Hughes Vs. The Censors

"The picture that couldn't be stopped!" trumpeted the tagline for "The Outlaw," Howard Hughes' fictional tale of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, with Doc Holliday and a little of Jane Russell's cleavage thrown in for good measure. The latter made the film one of the most controversial pictures of its day, and it would take the Hollywood mogul five years to secure the movie a wide release.

Producer and director Hughes had no qualms about using Russell's sex appeal to sell his movie; when it came to picking a young starlet to play her part from a nationwide casting call, Hughes chose Russell because her bust was the most to his liking. Much of the publicity was focused on the 19-year-old making her screen debut, resulting in one of the most famous and controversial images of '40s Hollywood: Jane Russell reclining in a haystack with a gun in her hand, dress hiked up to her thigh, one arm thrown back to accentuate her bosom, and the shoulder strap of her blouse hanging down provocatively. According to Christina Rice, author of "Mean...Moody...Magnificent! Jane Russell and the Marketing of a Hollywood Legend," Russell spent so long having her picture taken to promote the film that she was nicknamed the "motionless picture actress" (via EW).

The lengthy controversy that kicked off about "The Outlaw" was down to two things. Predictably for the era, the racy shots of Russell's body drew the ire of the Production Code Administration (PCA), aka. the Hays Code, and cuts would be needed before the film could be approved for release. The second factor was Howard Hughes himself.

So what happens in The Outlaw again?

There are plenty of classic Hollywood westerns that still hold up, but "The Outlaw" isn't one of them; playing fast and loose with historical figures, it throws together three legends of the Old West for a creaky and painfully stagey buddy comedy-thriller. Sheriff Pat Garrett (Thomas Mitchell) is happy to hear that his "best friend" Doc Holliday (Walter Huston) has arrived in town. The old gunfighter (Huston was 60, the real Holliday was 36 when he died) is looking for his horse, which he believes has been stolen by William Bonney, better known as Billy the Kid (Jack Buetel).

Holliday takes a liking to the young outlaw and refuses to help Garrett arrest him, which makes his old friend really mad. He banishes them from town but they stick around anyway and form a friendship. That night, Bonney decides to sleep in the barn and is attacked by a young woman called Rio MacDonald (Jane Russell) who is seeking revenge for her brother's murder. He overpowers her in a haystack and the film heavily implies that he sexually assaults her.

Things come to a head when the Kid guns down a stranger in self-defense. With no witnesses, Garrett arrives with his deputies to arrest him, but Holliday once again sides with the young gunslinger. They try to leave town but Garrett shoots The Kid, and Holliday responds by killing two of Garrett's men before making their escape to Rio's house, who just so happens to be Doc's sort-of girlfriend. She nurses Bonney back to health and they fall in love but gets angry when she realizes both men value the horse more than her. She tips off Garrett, setting up a protracted conclusion of double-crossing, oaths, and standoffs before a final showdown between the three men.

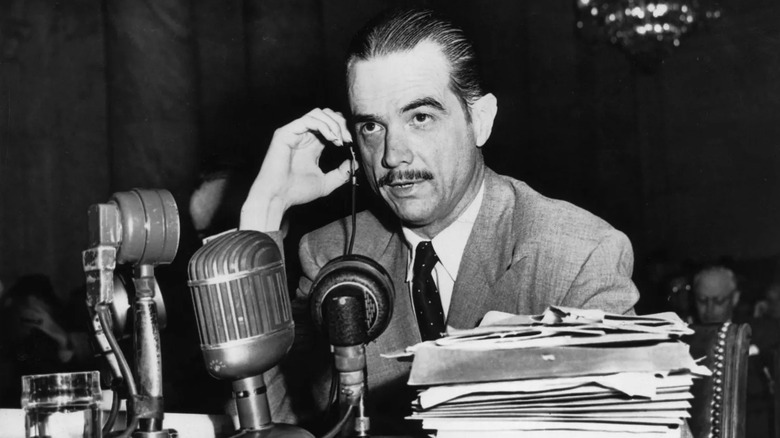

The adventurous and eccentric Howard Hughes

Howard Hughes was one of the richest and most influential people of the 20th Century; an aviator, engineer, magnate, and Hollywood mogul. He inherited the Hughes business and family fortune in his teens before embarking on a Hollywood career as a producer and director, making hits like "Hell's Angels" and "Scarface."

In the early '30s, he got into aviation, designing aircraft and making a series of record-breaking flights, including the speed record for flying around the world (via Britannica). More controversial were his military contracts during the Second World War, including the infamous "Spruce Goose." The H-4 Hercules was a wooden flying boat intended to carry 750 passengers; Hughes managed to get it up in the air for a mile before it was never flown again.

He dated some of the most famous women of the era: Ava Gardner, Rita Hayworth, Bette Davis, Katherine Hepburn, and Ginger Rogers among others, becoming notorious for his jealous and controlling nature (via NY Post). Eventually, however, he retreated into seclusion. In the '60s he took up residence at the Desert Inn in Las Vegas, which he bought when he was asked to leave (via History Collection). In later life, he suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder and feared germs, burning his entire wardrobe if he thought the clothes had become contaminated (via BBC). He locked himself away and watched the same movies repeatedly, ordering secretaries to wear gloves while typing his memos (via Time).

Even after he passed away in 1976, Hughes had a talent for the sensational. A former gas station attendant named Melvin Dummar claimed he had picked up a lost and disheveled Hughes by the side of the road in 1967 and was left $156 million in the tycoon's will, which was later revealed as a forgery (via New York Times).

Howard Hughes designed a new bra for Jane Russell

Jane Russell barely features as a character in "The Outlaw," but that didn't stop Howard Hughes from exploiting her figure for the film's publicity. He had become obsessed with her bust and, when it came to breasts, Hughes was a very serious guy. As one of his drivers revealed (via NY Post):

"If we saw a bump in the road, we were supposed to slow down to a maximum speed of 2 miles an hour and crawl over the obstruction so as not to jiggle the starlet's breasts. Hughes was one of the world's consummate t*t men, and he was convinced that women's breasts would sag dangerously unless treated gently and supported at all times."

The famous haystack photos were key to creating buzz for the film before it was even released, and during the shoot, Hughes wasn't happy with the way her bust looked. His solution to the problem was to use his engineering skills to design a "cantilevered" bra for Russell that would lift up her bosom and allow for maximum cleavage, a precursor of the modern push-up bra. She later said (via Vintage News):

"Howard decided it wouldn't be as hard to design a bra than it would be to design an airplane... [But] when I went into the dressing room with my wardrobe girl and tried it on, I found it uncomfortable and ridiculous. Believe me, he could design planes, but a Mr. Playtex, he wasn't."

She privately ditched it in favor of one of her own bras, tightened and padded to give the desired oomph Hughes wanted for the pics. It worked, and the images made Russell one of the favorite pin-ups for American GIs serving abroad during the Second World War.

Howard Hughes generates controversy against his own movie

Although the shooting of "The Outlaw" wrapped in early 1941, it would take another two years for its first theatrical release. With Jane Russell's bosom playing such a prominent role in the publicity and the film itself, Howard Hughes found himself in hot water with the Product Code Administration (PCA). The director, Joseph Breen, sent a memo regarding the breast issue (Via AFI):

"In my more than ten years of critical examination of motion pictures, I have never seen anything quite so unacceptable as the shots of the breasts of the character of Rio...Throughout almost half the picture the girl's breasts, which are quite large and prominent, are shockingly emphasized."

It wasn't just the boobs that Breen had a problem with. There was also the issue of "illicit sex between Billy and Rio," "undue brutality and unnecessary killings," and the thematic no-no that Billy the Kid is a "major criminal who goes unpunished."

Hughes eventually acquiesced to the long list of cuts required to get the film released, including around 30 seconds of Russell, but that still didn't stop him from trying to sneak an uncut version past various state censor boards after Breen had left his position at the PCA. That idea backfired when some local authorities wanted even more cuts than the Hays Office and 20th Century Fox, the film's initial distributor, faced a hefty fine if they released the unapproved version of the picture. Hughes continued his battle against the censors for the rest of 1941 but eventually had to shelve the project because he suddenly had more important things to think about. The United States joined the war in December of that and Hughes had to concentrate on making planes instead of movies.

The Outlaw is finally released and becomes a hit

Howard Hughes' publicist, Russell Birdwell, spent much of 1942 promoting Jane Russell as Hollywood's next big thing, even though no one had seen "The Outlaw" yet. Meanwhile, Hughes stood to lose millions after 20th Century Fox pulled out of the distribution deal, even though he had begrudgingly made the cuts specified by the Hays Office. He wasn't prepared to let that happen, so he devised a scheme: He got on the phone with everyone he knew and spread rumors about the movie's salacious content, whipping up a public outcry (and therefore demand) which forced the film briefly into theaters before it was approved (via Film Stories). The further hubbub was generated by the publicity focusing on Russell, with huge billboards of her image plastered around San Francisco ahead of its 1943 premiere asking, "How would you like to tussle with Russell?"

As with any kind of controversy surrounding a movie, it only drove more people to go see what all the fuss was about, and "The Outlaw" performed well on its initial short-lived run in San Francisco. Then it was promptly withdrawn again before a wider release after it was revealed that only one copy of the seven in circulation contained the required cuts.

"The Outlaw" would receive a re-release in 1946 amid another flurry of controversy, bans, complaints, and court appeals, eventually becoming a major box office success and catapulting Jane Russell to stardom.

Nowadays there is little in the film to titillate or scandalize a modern viewer; it's tedious, talky, and, apart from a few gratuitous shots of Russell's cleavage, it's hard to even imagine what the fuss was all about. It just goes to show how much things have changed over the past 80 years in Hollywood.