The Night Of The Hunter's Murder Scenes Were Designed With Music In Mind

"The Night of the Hunter" may hold back from showing any murders onscreen, but that doesn't make Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) any less creepy. A fanatical Christian that's equally misogynist, Powell roams the Great Depression Ohio valley, marrying widows before robbing them of both of their largesse and lives. The not-at-all-good reverend sees no conflict between his faith and his black widowing. After all, the Bible is full of killings.

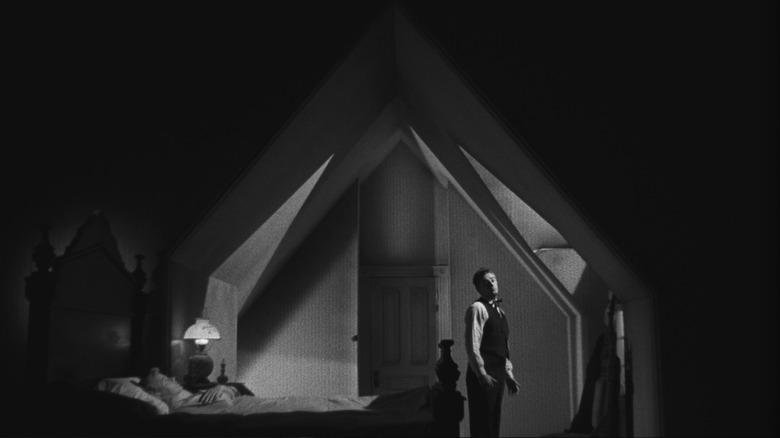

While Powell is said to have a high body count, only two of his killings are directly featured in "The Night of the Hunter." The film opens with him fleeing from one, catching a glimpse of his victim's lifeless legs from her basement door. Powell then marries Willa Harper (Shelley Winters) to find money stolen and hidden away by her late husband. After brainwashing her into his faith, he disposes of her. She ends up being so robbed of her agency that she lays stiff like a corpse, while he prepares to stab her in her bed. The scene cuts away before the knife makes contact, but when we next see Willa, she's at the bottom of the river. Once more, the violence is portrayed only in the killing's aftermath.

In the opening, when a handful of young boys discover Powell's victim, the musical cue is blaring horns (a typical horror/thriller score). During Willa's murder, though, the score is a whimsical waltz in constant battle with the horns; the horns only win out when Powell decides to kill Willa. When the film cuts to her corpse underwater, the whimsy returns. The score of these moments didn't come from the film's composer, Walter Schumann, but from cinematographer Stanley Cortez.

Laughton and Cortez depend on each other

While Charles Laughton was an experienced actor, "The Night of the Hunter" was the first (and tragically, only) time he directed a film. Stanley Cortez, on the other hand, had been shooting movies since the 1940s and made pictures with directors including Orson Welles and Fritz Lang. Laughton and Cortez first worked alongside each other in the 1950 film noir "The Man on the Eiffel Tower." According to "Charles Laughton, A Filmography: 1928 – 1962," Laughton may have ghost-directed certain scenes of that film. If so, he must have worked well with Cortez, at least enough to hire him for his first credited feature.

Speaking to The American Society of Cinematographers in 1984, Cortez recalled shooting "The Night of the Hunter" and working with Laughton. Cortez praised Laughton's ability to work with actors and his philosophical aptitude, but said the director relied on him for the technical side of things:

"Charles did not know too much about camera technique. He depended on me completely, and I'm not saying this with ego, that's the truth, because this is what Charles wanted because Charles did not know ... I used to go to Charles' house where I would explain to him what different lenses would do, and what the height of the camera would do."

That's not to say Cortez was the film's true director. No, "The Night of the Hunter" is Laughton's vision, he just needed a guiding hand in bringing it to life.

Composing to the scene

In another interview with American Cinematographer magazine, Stanley Cortez revealed the origin of the murder scene's music. "I am a devoted student of music, so much so that I use music a great deal to give me a clue to a given problem," said Cortez. When preparing to shoot the scene in question, he started thinking of the orchestral piece, "Valse Triste" by Jean Sibelius. Laughton noticed something was on Cortez's mind and, after some prodding, the DP shared it with his director. Laughton's reaction? 'Damn it! How right you are! [The scene's score] has to be a waltz!'

Laughton was so convinced by the idea that he took extra steps to ensure the scene and score complemented each other. Cortez recounted:

"Then, [Laughton] did something that never happened in my career before — it may even be unique in the industry. He sent for the composer, Walter Schumann, to come on the set and see what I was doing visually so that he, Schumann, could interpret it aurally. And that's how the waltz tempo of that scene got started."

So, why of all the music in the world did Cortez think of "Valse Triste" at this moment? He explained:

"[The music] told of a scene that takes place in a graveyard at one minute past midnight. Bones come to life and do a dance in sheer mockery of life, which was the exact thing Mitchum was doing because of the love and hate thing."

Everything about the underwater scene, from the even lighting to Willa's preserved body to her hair and sea plants swaying in the waves, feels ethereal. The waltz completes the mood.