The Story Of Kundun, The Martin Scorsese Film That Disney Tried To Bury

It's been 25 years since Martin Scorsese made "Kundun" and inspired an almighty political battle between Disney and the Communist government of China, and it's time one of his most underseen films got its due.

'Tis the season for Martin Scorsese Discourse. Well, in fairness, it feels like the endless, frequently bad-faith conversations surrounding one of our greatest living filmmakers has become a year-round event. Ever since Scorsese made his nuanced and perfectly reasonable comments about Marvel Studios and the creative curiosities of their cinematic output, poor Marty has been subjected to all manner of Film Twitter nonsense. It's baffling that one of the art form's most ardent champions, arguably the most cine-literate person in the industry, has been positioned as some kind of gatekeeping bully against the scrappy underdog that brought us the highest-grossing film franchise of all time. It's all very silly, of course, but also deeply ignorant of Scorsese's own work.

We could be here all day discussing his incredible filmography, the marginalized directors he supports as a producer, his investments into the restoration and preservation of rare films, or his work with the World Cinema Foundation and African Film Heritage Project. Here's a man who has walked the walk. He's also someone who keenly understands what it truly means to see his work be in the grips of gatekeepers and swept under the rug by corporate interests. After all, this is the man who dared to make "Kundun."

Exploring new territory

In 1997, Scorsese decided to follow up his lavish and ultra-violent crime thriller "Casino" with, naturally, a grand biographical drama about Tenzin Gyatso, the fourteenth Dalai Lama. The film was the pet project of screenwriter Melissa Mathison, perhaps best known for writing "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial." She even met with the Dalai Lama to ask if she could write about his life. He agreed and sat down for interviews that would form the foundations of her script. While she had never worked with Scorsese before, Mathison felt he would be a strong choice to direct "Kundun" because he had a sharp understanding of faith, thanks to his own Catholic background (he famously almost became a priest instead of a director). While the bad-faith discourse repeats the claim that Scorsese only makes uber-macho gangster films, Scorsese also made tender period dramas like "The Age of Innocence" and savvy dramas of women's independence such as "Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore."

Yet this was new territory for the filmmaker — a biopic focused on the youth of a revered religious figure who is still alive and the subject of immense political strife. Not only that, but the movie would contain an ensemble of entirely unknown actors. It was a tough sell, but it did have one giant in its corner: Disney. If any distributor could make such a story a hit, it was them. Soon, Scorsese had set up production in Ouarzazate, Morocco (for reasons that will soon become clear, actually filming in Tibet would have been impossible). While the budget was relatively low -– a reported $28 million -– it would prove to be an ambitious project.

Kundun at 25

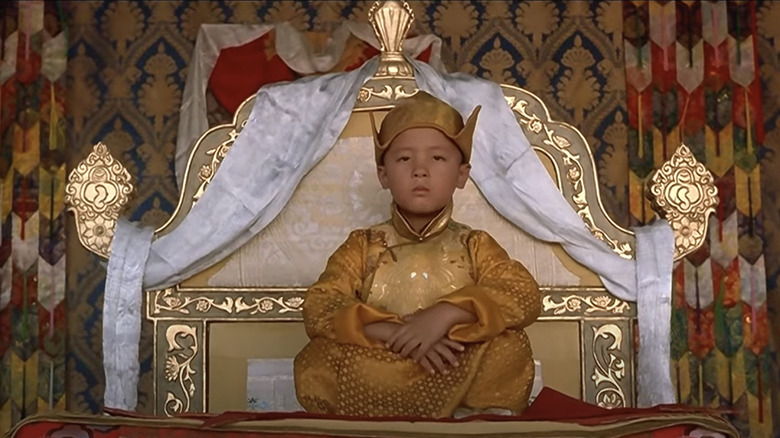

Even in the context of Scorsese's varied career (one far more diverse than his critics care to note), "Kundun" is a curious beast. It's a coming-of-age story about a young boy burdened with the weight of utmost divinity, a force of faith that is unwavering to those around him, never once called into doubt. His job is to be both more and less human, a being who embodies the most adored tenets of his faith. For the first half, "Kundun" is languidly paced, unconcerned with forced dramatics in favor of showing the idyllic beauty of Tibet and a way of life on the way out. Scorsese has always understood the perils of faith and the generational guilt it can inspire (at least from a Catholic perspective), but in "Kundun," belief is seen as bringing joy, peace, and a real sense of right in a world defined by wrong. For much of the first half, we see the perspective of a young boy who is being trained for greatness, yet is still a child who wants to laugh and play with the monks who kneel at his feet.

While he has never skimped on craft, Scorsese truly brought out the big guns here, utilizing one of Philip Glass's best film scores and cinematography by Roger Deakins that glows without descending into cheap, sentimental aesthetics. It's not without faults, however. More concerned with feeling than narrative flow, the film doesn't dig much deeper into the Dalai Lama's life beyond the beats casual observers are already familiar with. It's also entirely in English, which was probably a concession to American audiences but can't help but feel at odds with the rest of the film's strive for authenticity. Still, the end result of "Kundun" is a fascinating and intimate epic that feels unlike anything else in Scorsese's filmography, yet entirely in line with his recurring thematic concerns. It's a miracle it got made and a perfect example of a film that simply would not be greenlit by a major studio in 2022. Perhaps less surprisingly, it didn't face an easy journey towards release.

How the Chinese government tried to censor Scorsese

Before the film even reached theaters, the Chinese government began its pushback against "Kundun" and Disney. In China, the Dalai Lama is seen as a dissident and a threat to the country's rule over Tibet. They have repeatedly tried to dispute his legitimacy and quash support for the Tibetan separatist movement, including reportedly torturing prisoners. The government's stranglehold on culture continues to this day, but in the '90s, China's decision to open their market to international prospects proved too irresistible a boon for Hollywood to ignore. Disney greatly benefitted from this shift and began to invest more and more into the Chinese market. At the time, the company was lining up plans for theme parks in the country, wider releases of its biggest movies, and films tailored to suit the tastes of Chinese audiences. But the distribution of "Kundun" threatened to ruin all of those opportunities.

The Chinese government banned Scorsese and Mathison from entering the country. They started pulling Disney films and series from circulation. Disney initially planned to stand by "Kundun," telling Time Magazine in December 1996 that they would move forward with the film's release as planned. That changed very quickly. The film didn't perform well at the box office, grossing only $5.7 million globally. While Scorsese would, at the time, praise Disney for standing by "Kundun" through it all, the truth was far darker.

Disney's lackluster response

Disney went overboard trying to make it up to the Chinese government. Michael Eisner, then the CEO, hired former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (who was accused of being a war criminal) as an emissary to China. It was his job to assure the Chinese powers-that-be that "Kundun" was all a silly mistake. According to James B. Stewart's book "Disneywar," Eisner told the Chinese that "Kundun" would "die a quiet death" because Disney would not heavily promote it. In 1998, Eisner apologized for the movie in a conversation with China's premier, calling it a "stupid mistake." He then had the nerve to laugh that "nobody watched" the movie, and that "in the future we should prevent this sort of thing, which insults our friends, from happening." The following year, Disney released "Mulan," which received a major rollout in China. To this day, Disney continues to market their work heavily to Chinese audiences, including filming the live-action version of "Mulan" in the country. Some shooting took place in Xinjiang, an autonomous region where re-education camps are located, designed to imprison and torture Uyghurs and other Muslims. Disney has never fully responded to complaints about this.

Even with Scorsese's reputation as one of the greatest filmmakers on the planet, "Kundun" remains sinfully underseen, all but buried by Disney even a quarter of a century after its initial release. While it is available on Blu-ray and DVD, it's not on any streaming service and is seldom offered special or repertory screenings. To my knowledge, Disney has never offered any sort of mea culpa for treating it as a pawn in a bargaining game with a censorship-wild foreign government. If even the most iconic of directors, a multi-million-dollar grossing award-winner, can't avoid being censored in this manner by his own colleagues, what hope does the rest of Hollywood have?

Yet for all of the unfortunate drama surrounding "Kundun," it remains a stunning and challenging film about the ways that faith intersects with politics and personhood. To quote Christopher Moltisani in "The Sopranos": "Marty! 'Kundun!' I liked it!"